Figure #1: Vertical

cross-section of

the eye.

- Anterior chamber

- Cornea

- Suspensory lig.

- Ciliary body

- Sclera

- Choroid

- Vitreous chamber

- Optic disc

- Retina

- Lacrimal gland

- Eyelid

- Pupil

- Iris

- Lens

basic anatomy and terms | nasolacrimal duct system | keratoconjunctivitis sicca (kcs) | globe or eyeball | entropion | ectropion | cherry eye | tumors of the eyelid | conjunctivitis | keratitis | ulcerative keratitis | pannus | corneal dystrophy | lenticular sclerosis | cataract | luxation and subluxation of the lens | anterior uveitis | degeneration of the retina | detatchment of the retina | cancers | eye medications

Introduction: It is important to examine dogs’ eyes on a routine basis. Repeated examination allows one to become familiar with the normal appearance of the eye, so any abnormalities will be noticed immediately. Signs of an eye problem vary tremendously and may include cloudiness, tearing, squinting, discharge, redness, blinking, swelling, an increase in blood vessels, or changes in the size or shape of the pupil. Dogs may paw at the eye or rub it in an attempt to relieve irritation and itching. Any change in the eye or surrounding tissue may signal a problem and should be a cause for concern.

Many different problems can result in the same set of disease signs, so diagnosis cannot be made by clinical signs alone. Physical examination and special tests are needed to properly identify the cause of the problem. Tests may include a fluorescein dye test, a test for tear production called a Schirmer test, tests to measure pressure within the eyeball, and ocular examination with different types of lenses. The eye may be dilated to allow for proper visualization of the back of the eye.

Eye problems should be brought to the attention of a veterinarian immediately. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can prevent further eye problems that can lead to loss of sight. In addition, changes in the eyes may be a sign of whole body disease. By immediately identifying and reporting any changes, diseases can be diagnosed early and treatment can begin.

Although all eye problems should be reported to a veterinarian, it is important for the dog owner to identify and recognize common eye ailments. The eye is composed of several parts, all of which can be injured or become diseased. Eye problems and diseases can affect one portion of the eye or simultaneously be found in several areas.

Basic Anatomy and Terms: The eye is protected by upper and lower lids, as well as a third eyelid, called the nictitating membrane. Glands which produce tears are located under the lids. The front portion of the eye itself is covered with a thin, clear covering called the cornea. The remainder of the eye is covered with dense white tissue, the sclera. The margin of the cornea and the sclera is called the limbus. The episclera is the outside surface of the sclera. The conjunctiva is the tissue which reflects from the inside of the eyelids onto the globe. Glands which produce tears are also located in the conjunctiva.

The iris is the colored portion of the eye; the black open space in the iris is the pupil. Behind the pupil is the lens. The lens is attached to the ciliary body. The back of the eye is covered with a layer of tissue called the retina. The inside of the globe is filled with a clear fluid called aqueous humor. This fluid is produced by the ciliary body and nourishes the eye while helping to maintain its shape. This fluid is continually produced and drained from the eye. Drainage occurs at the iridocorneal angle, also called the drainage or filtration angle.

Glossary of Eye Terms:

|

Figure #1: Vertical

|

|

Copyrighted graphic used by permission from Anatomy of Domestic Animals, Sudz Publishing (email: sudzpub@mac.com)

Nasolacrimal Duct System and Lacrimal System

If there is a problem with any part of the system, drainage of tears from the eye may be impeded. If the tears do not drain into the duct system, they will spill over onto the face, creating a condition called epiphora. Signs include wet facial skin and a reddish, rusty stain to the skin and hair near the inner corners of the eyes.

Problems Associated with the Nasolacrimal System

Problems Associated with the Lacrimal System

Introduction: Tears are produced by the lacrimal glands, the accessory lacrimal glands, and the gland of the third eyelid. The tear film is actually three different layers - mucin (protein), serous (water), and lipid (fat). These different components of the tear film are made by different glands in the eye. Problems related to the lacrimal system cause a reduction in tear production and/or a change in the composition of the tear film. A decrease in tear production can be caused by injury or removal of the tear-producing glands, destruction of the glands, or infections. Inadequate tear production can lead to severe irritation of the cornea and surrounding structures. In addition, inflammation, infection, or destruction of one type of tear gland may result in alteration of the composition of the tear film and cause disease even if it appears that adequate amounts of moisture are being produced.

|

|

Diagnosis is based on visual examination and the use of a Schirmer tear test.

This test demonstrates the reduction or lack of tear production. Fluorescein

staining may show cornea irritation, abrasion, or ulceration. Blood tests may

confirm the presence of autoimmune disease.

Treatment involves restoration of the tear film and treatment of secondary

infections and inflammation. The eye must be cleaned before any medications

are administered to ensure the efficacy of the medications. This can be done

with sterile saline eye washes or tear solutions. Conservative therapy

involves the use of artificial tears and lubricants administered several times

per day, topical antibiotics, topical corticosteroids to treat inflammation,

and if indicated, drops that break up mucus. Primary therapy involves

increasing tear production by reducing the immune system’s destruction of the

lacrimal glands. This is accomplished using a topical medication called

cyclosporine. Approximately 75% of dogs respond to treatment with cyclosporine

by increasing tear production. Other therapies that increase tear production

include pilocarpine, and if needed, surgery to transplant the parotid salivary

duct into the corner of the eye. Additional surgery may be needed to treat

corneal ulceration if it is present.

Prognosis depends on the length of time between the onset of disease and

treatment, as well as the individual’s response to treatment with

cyclosporine. Treatment should be instituted as early in the course of the

disease as possible. If treatment is delayed, vision-impairing corneal changes

can occur. Most dogs respond to treatment with cyclosporine, so surgical

therapy can be avoided. Topical treatment may need to be continued for the

life of the pet.

Problems with the Eye and Associated Structures:

Globe or Eyeball

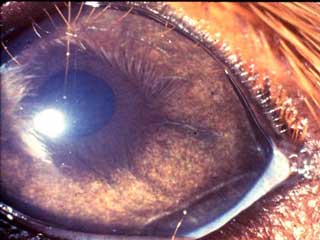

Acute glaucoma has a rapid onset. The rapid increase in intraocular pressure results in an extremely painful eye. The pain can cause eyelid spasm and epiphora. The dog may resist examination, refuse to eat, be depressed, and even cry out from the pain. In addition, ocular discharge, redness, and cloudiness may be noticed.

|

|

Diagnosis is based upon examination of the eye and measurement of the pressure

in the globe. Upon examination, the glaucomatous eye may have cloudiness,

corneal edema, redness, and engorgement of the blood vessels in the episclera.

The pupil may be dilated and unmovable. The globe may be enlarged and firm to

the touch. Accompanying problems such as uveitis, a luxated lens, or neoplasia

may be noted. Specific eye examination may show a closure of the normal

drainage area of the eye. The blood vessels in the retina may be compressed by

the increase in pressure. Measurement of the intraocular pressure will show it

to be elevated. Definitive diagnosis is based on measurement of an elevated

intraocular pressure. Acute glaucoma can very rapidly lead to blindness.

Total, irreversible blindness can occur in as little as 24-48 hours.

Treatment of acute glaucoma is considered an emergency. Rapid treatment may

prevent permanent blindness. If the glaucoma is secondary to an underlying

cause, treatment of the primary cause may result in resolution of the

glaucoma. Medical treatment is initially used for treatment of primary

glaucoma. Medical treatment may include diuretics, such as mannitol, and

topical medications to reduce aqueous production. Drugs can be applied

directly to the eye to reduce aqueous humor production, including carbonic

anhydrase inhibitors such as dichlorphenamide, and B-adrenergic

antagonists such as timolol maleate. Other drugs that help to open drainage

and enhance the outflow of aqueous humor may be tried. These include

pilocarpine and demecarium bromide.

If medications are insufficient to lower the intraocular pressure, surgical

treatment is needed. Surgery may be done to reduce the production of aqueous

humor and to create drainage. Laser treatment may be used. A combination of

medical and surgical therapies may be needed for long-term control of the

problem. It is important to note that if only one eye is involved, both eyes

should be medicated. If treatment is not successful and blindness results,

removal of the eye may be recommended to eliminate the pain associated with

the condition. If complete eye removal (enucleation) is unacceptable, the

contents of the eye may be removed (eviscerated) and an insert is placed

inside the eye (intraocular prosthesis) to maintain its form.

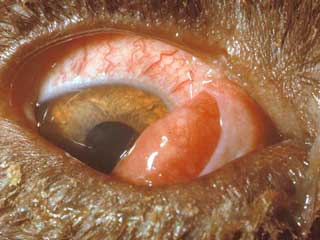

Chronic glaucoma occurs if the signs of acute glaucoma go unnoticed, or if

acute glaucoma therapy is not effective. The signs may include all of those

noticed with acute glaucoma, although to a lesser degree. The most obvious

sign is the enlarged globe. In addition, corneal ulceration, lens luxation,

cataracts, and keratitis may occur. Ocular examination will show degeneration

of the retina and the head of the optic nerve. The animal is typically blind

in the affected eye. Diagnosis is based on the physical and ocular

examination.

Treatment is aimed at reducing the pain of chronic glaucoma. The blindness is

not reversible. The medical and surgical treatments described for the control

of acute glaucoma may be used. Removal of the eye may be needed to control

pain. If only one eye is affected, the normal eye should be examined and

monitored for any signs of glaucoma. Preventative (prophylactic) treatment of

the unaffected eye should be started if indicated by ocular examination.

Prognosis for treatment of glaucoma depends on the underlying cause and the

time between onset of disease and treatment. Treatment to maintain or restore

vision will be unsuccessful in acute glaucoma cases unless initiated within

hours of onset. Chronic glaucoma patients may be blind before treatment

begins. Secondary glaucoma cases can resolve following successful treatment of

the primary cause. This can occur with glaucoma secondary to lens luxation.

Primary glaucoma patients require continual therapy to ensure any measure of

therapeutic response. Even with prompt medical treatment, over 90% of patients

will lose vision within one year of initial diagnosis. With surgical

treatment, approximately 60% will still have vision in the affected eye one

year later. Approximately 50% of dogs with one diseased eye will have the

other eye affected within one year if the second eye does not receive

preventative treatment.

Eyelids

Introduction:

Dogs have three eyelids. The upper and lower lids help to protect the eye from the environment, distribute tears over the entire eye surface, and control the amount of light that enters the eye. The third eyelid is located in the inner corner of the eye and sweeps across the eye as it closes. It functions to protect and lubricate the eye. It has its own set of tear glands that produce lubricating tears for the entire eye.Problems with the lids can result in pain, swelling, redness, excessive tearing, and drainage from the eye. Dogs with lid pain may rub their eyes, paw at their faces, squint, and show other signs of pain. Problems with the lids can lead to additional problems with closely associated structures such as the cornea, conjunctiva, and nasolacrimal drainage system of the eye.

|

|

Diagnosis is based on physical examination. Treatment involves eye medications

such as antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medications to treat underlying

causes of squinting and spasm. Temporary sutures may be placed to evert the

lid and decrease irritation to the eye. Once underlying causes are treated,

those cases that continue to have entropion are treated with surgical

techniques to roll the eyelid out and reduce irritation. Puppies are often

treated with temporary sutures. Permanent surgery is not performed until the

dogs reach full body size at about 6 months of age. If not treated, permanent

irritation and scarring of the cornea can result, along with chronic tearing

and pain. Prognosis is good with proper therapy and surgery as needed.

|

|

|

|

This condition may be seen in any dog, but can commonly be found in breeds

such as beagles, bloodhounds, bulldogs, cocker spaniels, Lhasa apsos, shih

tzus, and other dogs with shortened faces.

The condition is diagnosed on physical examination by the appearance of the

red, round to oval mass coming up over the edge of the third eyelid.

Accompanying signs can include squinting, repeated blinking, increased

tearing, and a reddening of the conjunctiva.

Treatment includes topical medications to reduce swelling and irritation,

along with a surgical procedure where the gland is sutured back in place. If

replacement is not successful, the gland can be removed, but removal is

neither the best nor the first method of treatment. Removal of the gland can

result in lack of tear formation that leads to development of corneal and

conjunctival problems. Surgical removal is therefore avoided if it is at all

possible to replace the gland. Topical therapy with anti-inflammatory eye

medication, such as corticosteroids, may be helpful to reduce swelling before

surgery and is important as an aid to help the eye heal after surgery.

Prognosis is good with prompt surgical repair.

|

|

Diagnosis is based upon physical examination. Treatment involves removal of

the mass by appropriate surgical techniques, which will vary depending on the

size and location of the mass. Reconstructive eyelid surgery may be needed.

Prognosis is typically good, but depends on the size and type of the mass. The

majority of masses are benign and removing the mass will usually cure the

problem. If removal is not complete, many masses will return. Most malignant

masses are also controlled by surgical removal.

Conjunctiva

Introduction:

The conjunctiva is the membrane that lines the inside of the eyelids and the third eyelid, and covers the outside of the sclera. The conjunctiva is a mucous membrane with an excellent blood supply. It connects the lids to the globe and contains specialized glands. These glands produce the inner layer of the tear film. Problems affecting the conjunctiva may be limited to only the conjunctiva or may involve other portions of the eye. Conjunctival inflammation or disease may also signal illness that affects the entire body. It is important to recognize whether disease processes are limited to the conjunctiva, extend to other parts of the eye, or signal whole body (systemic) disease.

|

|

Conjunctivitis is diagnosed on physical examination. Additional specific tests

are performed to identify other eye problems and to rule out other eye

diseases that can lead to conjunctivitis. These include a Schirmer tear test,

fluorescein dye, intraocular pressure test, bacterial culture and sensitivity,

and if indicated, conjunctival cytology. Steps are taken to identify any

underlying or accompanying disease situations that contribute to the

conjunctival inflammation.

Treatment involves both medicating the conjunctiva and treating any underlying

or secondary problems. For example, dogs with allergic conjunctivitis may need

skin testing for inhalant allergies and appropriate immunological therapy

(allergy injections), while dogs with a foreign body imbedded in the

conjunctiva will require sedation and removal of the object. Dogs with

underlying eye disease, such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, will require long

term therapy to modify tear production, while those with an occlusion or

blockage of a nasolacrimal duct may respond to a flush of the duct system.

Depending on the cause of the conjunctivitis, treatment may include topical

medications to control inflammation and infection, eye washes to remove

discharge, lubricants to add moisture to the eye, and medications to control

infection and inflammation. Topical therapy may include antibiotic agents,

corticosteroids, or combination medications. All discharge should be flushed

from the eye before treatment is attempted to allow the medications to contact

the surface of the eye and the conjunctiva.

Prognosis depends on the underlying cause and severity of the condition.

Simple bacterial conjunctivitis is typically very responsive to treatment with

the appropriate antibacterial medications. Secondary conjunctivitis may not

respond until the underlying cause is identified and treated. Some secondary

conjunctivitis problems may be controlled, but not totally eliminated.

Cornea

Introduction:

The cornea is the outer, transparent layer of the front of the eye. It protects the eye while still allowing light to pass through. The cornea is protected by a layer of tears and by continuously replacing its superficial cells. It lacks blood vessels (which helps make it transparent), and so does not heal easily. Any disease process or insult to the cornea can result in cloudiness, swelling, or pigmentation, which in turn may lead to loss of vision. Corneal irritation or inflammation is extremely painful. It is critical to treat any corneal problem as rapidly as possible.

|

|

|

|

Diagnosis is based on ocular examination and fluorescein dye testing. If

needed, specific examination of the interior of the eye and cytology can

also aid in the diagnosis. Other tests, such as a Schirmer tear test, are

performed to rule out additional or contributory eye diseases.

Treatment involves elimination of the cause, along with specific treatment

for the ulceration and inflammation. Underlying eye problems, such as

keratoconjunctivitis sicca, entropion, or ectropion, should be treated

appropriately. Treatment of the ulcer may include topical antibiotics to

prevent infection, topical atropine to control pain, specific medications to

control fungal or viral infections, and if indicated, specific medications

to prevent collagen breakdown. Dogs may be placed on systemic non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) medications such as aspirin.

Some ulcers are treated with protective contact lenses. Others may require

surgery to trim (debride) the ulcer edges. Additional surgical procedures

include punctuate keratotomy, conjunctival flaps, and flaps created from the

nictitans. Proper use of an Elizabethan collar or similar device will

prevent the animal from scratching the healing ulcer. Eyes should be

rechecked at approximately 3-day intervals; those with deep ulcers should be

rechecked daily until satisfactory healing is observed.

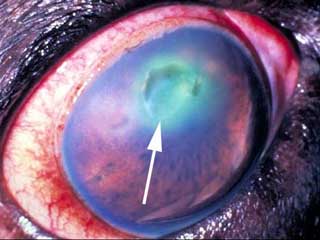

Refractory corneal ulcers are a group of ulcers that do not heal

with traditional therapy. They are also called indolent ulcers, recurrent

erosions, and boxer ulcers. Refractory ulcerative keratitis may occur in any

breed, but was originally identified in boxers, and the breed is noted for a

tendency towards this condition. Refractory corneal ulcers are identified by

specific characteristics on ocular examination, which include separation of

the corneal epithelium from the underlying corneal layers.

Treatment for these refractory ulcers involves physical and chemical

debridement of the ulcer to remove abnormal epithelial tissue and allow

healing. Additional surgical therapy includes: nictitans flaps, conjunctival

flaps, superficial keratectomy, transplantation of healthy corneal

epithelium (keratoepithelioplasty), and multiple punctuate keratotomy.

Corneal contact lenses, tissue adhesives, and eye shields made of collagen

can also be used. As with other corneal ulcers, topical antibiotics and

analgesics are indicated to control infection and pain. Treatment of

refractory ulcers can take weeks to months depending on their severity.

The prognosis for ulcerative keratitis depends on the underlying cause, the

severity of the ulceration, the type of treatment employed, and response to

therapy. Simple, superficial ulcers often heal nicely in approximately one

to two weeks. Deeper ulcers treated with surgical techniques may require 4-6

weeks to heal; those treated without surgery may take longer, or never heal

satisfactorily. Refractory ulcers may remain unhealed for months unless

treated with surgical techniques. After surgery, repair may occur in 2

weeks, and conjunctival flaps may be left in place for a month or longer.

Untreated or incorrectly treated corneal ulcers can progress, resulting in

rupture of the cornea and loss of vision. This often results in removal of

the globe.

|

|

Prognosis is based on severity of the condition, age, and breed of the dog.

For example, younger German shepherds have a worse prognosis than those

afflicted at an older age. Lack of treatment can lead to blindness in

affected dogs. Continuous treatment can allow many dogs to retain vision for

their entire lives. Periodic rechecks are recommended to assure that the

treatment is effective and to monitor any disease progression.

Neurologic keratitis may occur in dogs that have lost nervous input to

the eye, often as a result of trauma. The loss may occur to the sensory

nerves, resulting in lack of feeling in the eye, or from damage to the motor

nerves, resulting in an inability to close the eyelids. The results are

irritation and inflammation of the cornea. Treatment involves the use of

ocular lubricants as well as medications to decrease infection and

inflammation. Surgery may be performed to close the eye temporarily to allow

the nerves to repair. Permanent closure of the lids or removal of the eye

may be necessary if the damage to the nerves is permanent.

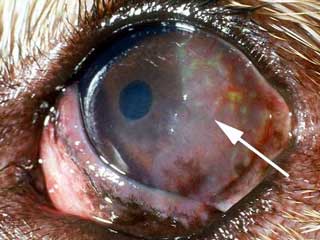

Nodular granulomatous episclerokeratitis is seen primarily in herding

breeds, such as collies, Shetland sheepdogs, and border collies. It is seen

in both eyes. It is characterized by the appearance of raised, pinkish

lesions on the outer (lateral) part of the cornea. The proliferation of

cells occurs typically at the junction of the cornea and the sclera. The

lesions are vascular in nature and may appear symmetrical. The disease is

believed to be immune-mediated. Treatment involves the use of

anti-inflammatory agents, such as corticosteroids or azathioprine. Because

the lesions return, surgical removal typically does not cure the problem;

therefore, medical control is the treatment of choice.

Superficial Punctate Keratitis: This condition is characterized by a

diffuse inflammation of the cornea. The areas of inflammation can be

scattered across the cornea. This condition can be caused by viruses,

chronic exposure of the eye to the environment, and topical irritants, such

as topical anesthetic agents. Diagnosis is based on examination of the

cornea. Treatment is based on removal of the underlying cause, along with

prevention of infection and reduction of inflammation.

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is often referred to by its initials, KCS.

This condition involves inflammation of both the cornea and the conjunctiva

due to insufficient and abnormal tear production. It is discussed

above with problems of the lacrimal system.

Lens

Introduction:

The lens focuses light waves that come through the pupil. It is held in place by small suspensory ligaments called lens zonules that attach the lens to the ciliary body. The ciliary body can contract and relax, thereby changing the shape of the lens. The changing shape of the lens allows it to properly focus light waves from different distances onto the retina.

|

|

Treatment is reserved for cataracts that cause blindness. There is no

effective medical therapy. A limited number of cataracts will spontaneously

resorb. Spontaneous cataract resorption is an unpredictable process that may

or may not result in improved vision. It tends to occur in certain breeds of

dogs and in animals that are under 6 years of age. It is not advisable to

delay treatment while attempting to wait for spontaneous resorption. Treatment

involves surgical removal of the lens. The lens can be replaced with a

prosthetic lens if desired. Although several techniques can be used,

phacoemulsification is commonly used today. This technique involves the use of

a small ultrasonic probe that is placed into the eye. It shatters the cataract

and then removes the broken-down debris by suction.

Prognosis depends on the severity of the cataract, the cause of the cataract,

and the time between identification and surgical removal. Success rates with

phacoemulsification are greater than 90%. The best prognosis is associated

with hereditary cataracts treated early in their course. The worst prognosis

is associated with long standing cataracts that are found in conjunction with

other ocular problems, such as uveitis or degeneration of the retina. Dogs

with retinal degeneration are not candidates for cataract removal because they

will not regain sight after the procedure.

Uvea

Introduction:

The uvea is a very vascular structure that is critical for the maintenance of a healthy eye. It is a pigmented, vascular tunic that sits between the outer fibrous layer of the eye (cornea and sclera) and the inner nervous layer (retina). It is comprised of 3 connected portions - the iris, the ciliary body, and the choroid. The anterior uvea is made up of the iris and the ciliary body. The posterior uvea, located towards the back of the eye, is comprised of the choroid. The iris controls the amount of light that enters the eye. The ciliary body controls the focus of the lens, produces aqueous humor, and helps regulate intraocular pressure. The anterior uvea acts as a blood-aqueous barrier and prevents unwanted particles from the bloodstream from entering the aqueous humor. The choroid provides nourishment to the retina and most diseases of the choroid are linked to disease of the retina.Because the uvea is highly vascular, it is very reactive to changes in the body and is easily inflamed. Inflammation of the uvea is called uveitis. Specifically, inflammation of the iris and ciliary body is termed anterior uveitis. Posterior uveitis refers to inflammation of the choroid. Inflammation may be limited to only the anterior or posterior uvea, or involve both portions. Inflammation of the uvea allows particles to cross the blood-aqueous barrier and enter the aqueous humor. This causes an inflammatory response in the aqueous which can lead to a reduction or total loss of vision.

|

|

Diagnosis is based upon complete physical and ocular examination. A thorough

eye examination includes measurement of the intraocular pressure. The pressure

is typically decreased with uveitis. Additional testing may include blood

testing, urinalysis, and radiographs to search for the underlying cause of the

disease.

Treatment is aimed at reducing the inflammation of the uvea while determining

and eliminating the underlying cause. Anti-inflammatory agents including

corticosteroids (1% prednisolone acetate, 0.1% dexamethasone) and

non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (flurbiprofen) can be applied topically.

Topical medications that dilate the pupil are also used (atropine). In some

cases, corticosteroids can be injected under the conjunctiva or administered

systemically. Those patients that do not respond to corticosteroids can be

treated with other immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine.

Treatment may be altered depending on the cause of the uveitis and the

systemic illnesses that are present. Treated animals should be re-examined

within one week following the initial treatment and re-evaluated every few

weeks.

Prognosis depends on the severity of the uveitis at the time of

treatment and the underlying cause of the uveitis. Early, aggressive treatment

of the uveitis and the initiating cause is necessary to prevent secondary

problems.

Prognosis is good if the underlying cause is identified and eliminated, and

appropriate eye therapy is instituted. If uveitis is left untreated, glaucoma,

lens luxation, and blindness can result. Successful treatment can involve

several months of continual medication and follow-up examinations.

Retina

Introduction: The retina is the back portion of the eye. It is considered the "film" that records the visual images that come through the cornea and are focused by the lens. The cells of the retina receive the light images. These cells are of two main types, rods and cones. The rods are sensitive to dim light and the cones are sensitive to bright light. The rods are useful at dusk, while the cones perceive images in the day and help distinguish colors.

The rods and cones translate the light images into chemical messages which affect adjacent nerve fibers. The retinal nerve fibers converge together at an area called the optic disc to form the optic nerve. The messages travel as nerve impulses along the optic nerve to the brain where they are again converted into visual images. Any type of damage to the retina will result in interruption of this process and cause loss of vision.

Introduction: Cancers may develop in any structure in the eye. They can be found in any age or breed of dog, but are generally more common in older animals. A cancer may be primary and arise from tissue in the eye, or be secondary to a cancer somewhere else in the body. Cancers located anywhere else in the body may migrate (metastasize) to the eye. Tumors may be localized nodules or locally invasive. In addition to occupying space, tumors may cause infection and inflammation of involved tissues. Common eye tumors include adenomas, adenocarcinomas, papillomas, melanomas, histiocytomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and fibromas. Tumors are more likely to be found on the eyelids than any other part of the eye.

A mass in or near the eye will cause signs that reflect the involved area of the eye. For example, dogs that have a mass on the lid or conjunctiva will demonstrate signs of blepharitis and conjunctivitis. A mass located on the retina may cause blindness and a dilated pupil. Signs associated with eye disease are not specific to one diagnosis, so ocular examination and diagnostic tests are necessary for proper diagnosis. Diagnostic tests may include special examination, biopsy, histopathology, and MRI testing. Microscopic examination will allow differentiation between inflammation, benign tumors, and malignant tumors. Treatment depends on the type and location of the growth and may include surgical removal, chemotherapy, and removal of the eye. Prognosis is dependent on the location and type of growth. Early identification and removal of malignant tumors will increase the probability of a successful outcome and reduce the risk of tumor spread.

* All of the pictures were used with permission from Colorado State

University Ophthalmology Service.

Eye Medications

Introduction: Eye medications can be delivered by several methods. Topical medications are applied directly to the eye surface. The topical medications may be available as eye drops and ointments. This method of administration is appropriate for both hospital and home treatment of eye diseases in dogs. In addition, veterinarians may administer medications via injection into the eye. Common sites for these injections are subconjunctival (beneath the conjunctiva), retrobulbar (behind the eye), or intraocular (into the eyeball).

In addition, diseases of the eye may be treated with medications that are given directly to the dog, either by mouth or by injection. Finally, eye diseases may not be limited to the eyes; they may be a sign of disease that is affecting the entire body. In this case, the veterinarian will prescribe medication to treat the primary illness, as well as to control the problems in the eyes.

The following table lists commonly used eye medications. Depending on the combination of related eye problems present at one time, a specific medication may need to be combined with other medications or be inappropriate for its original, intended use. All eye medications should be used under the guidance of a veterinarian. Page B224 of this manual has information on how to properly clean the eye and administer products.

| CLASSIFICATION/USE/INDICATION | MEDICATION | SPECIFIC USE NOTES | CONTRA-INDICATION (IF ANY) |

| EYE RINSES

USE: Clean, rinse, flush INDICATIONS: Clear mucus before instilling medications, remove debris

from eye |

Sterile, buffered isotonic solutions containing sodium chloride, sodium citrate, sodium phosphate | ||

| Combinations of water, boric acid, zinc sulfate | |||

| EYE LUBRICANTS USE: Lubricate, prevent eye irritation, relieve dryness INDICATIONS: Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, whenever general anesthesia is used, keratitis, ectropion |

Pilocarpine | Irritating, can cause conjunctivitis and worsen uveitis, not commonly used | Can affect respiration and cardiac function |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone | |||

| Polyvinyl alcohol | |||

| Methylcellulose | |||

| Ethylene glycol polymers | |||

| Refined petrolatum | |||

| Refined lanolin | |||

| Refined peanut oil | |||

| MUCOLYTICS

USE: Prevent collagen break-down, break up mucus INDICATIONS: "Melting" corneal ulcers, chronic conjunctivitis,

keratoconjunctivitis |

Acetylcysteine | Very expensive | |

| Autologous plasma | Sometimes used in place of acetylcysteine | ||

| ANESTHETICS

USE: Topical pain relief INDICATIONS: Minor surgery, eye examination, diagnostic procedures,

preoperative evaluation of entropion, removal of foreign bodies |

Proparacaine 0.5% | Never use therapeutically. May cause corneal irritation. | |

| Tetracaine HCl 0.5%* | |||

| ANTIBIOTICS (SINGLE)

USES: Preparation for an intraocular procedure. Treatment of infection (if possible, select specific agent for microbe; if testing is not possible, broad spectrum or combination antibiotic is preferred.) Preventive pre and/or post-procedure. INDICATIONS: Treat susceptible infections contributing to uveitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, keratitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Control secondary bacterial infections in conditions such as proptosis of the globe, entropion, ectropion, corneal ulcer, corneal abrasion. |

Chloramphenicol 0.5% solution and 1% ointment | Susceptible bacteria may include Staphlococcus, Streptococcus spp, Corynebacterium, Hemophillis spp, Moraxella, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma spp. | |

| Gentamicin 0.3% solution and 0.3% ointment | Susceptible bacteria may include Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Pseudomonas, Proteus spp, Escherichia coli, Hemophillis, Enterobacter, Moraxella | ||

| Tetracycline 1% solution and 1% ointment | Susceptible bacteria may include Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium spp,, Hemophillis spp, Moraxella, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma spp | ||

| Tobramycin 0.3% solution and 0.3% ointment | Susceptible bacteria may include Pseudomonas, Proteus spp, Escherichia coli, Hemophillis, Enterobacter, Moraxella, Staphylococcus | ||

| Bacitracin 500 U/g ointment | Susceptible bacteria may include Staphlococcus, Streptococcus, Corynebacterium spp | ||

| Chlortetracycline 1% ointment | |||

| Erythromycin 0.5% ointment | |||

| Neomycin 0.35% ointment | Susceptible bacteria may include Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium spp, Hemophillis spp, Moraxella, Enterobacter, Mycoplasma | ||

| ANTIBIOTICS (COMBINATION)

USE: Same as single antibiotic When more than one type of microbe is present or when testing for specific identification is not possible. INDICATIONS: Same as single antibiotic |

Neomycin sulfate, Polymyxin B sulfate solution and ointments | ||

| Neomycin sulfate, Polymyxin B sulfate, gramacidin solution | Preferable drug for broad spectrum coverage without culture/sensitivity | ||

| Neomycin sulfate, Polymyxin B sulfate, Bacitracin ointment | Preferable drug for broad spectrum coverage without culture/sensitivity | ||

| Oxytetracycline HCl, Polymyxin B ointment | |||

| ANTIINFLAMMATORY - STEROIDAL

USES: All allergic ocular diseases. Nonpyogenic inflammations of any ocular tissue. Reduction of scar tissue. Certain ocular surgeries. INDICATIONS: Blepharitis, conjunctivitis, proptosis of the globe, uveitis,

entropion, prolapse of the gland of the 3rd eyelid, keratoconjunctivitis

sicca, chronic superficial keratitis |

Prednisolone acetate suspension | Avoid when there is no specific indication for

steroid use.

Contraindicated in the treatment of corneal ulceration, viral infection, & keratomalacia. May promote fungal infections. May alter insulin requirements in diabetic dogs. |

|

| Dexamethasone | |||

| Triamcinolone (topical and injectable) |

|||

| Betamethasone (topical and injectable) |

|||

| Methylprednisolone acetate (injectable) | |||

| ANTIBIOTIC/STEROID COMBINATIONS

USES: Control inflammation and bacterial infection, treat acute and chronic inflammatory processes of the eye INDICATIONS: Acute or chronic conjunctivitis, inflammation of the anterior segment of the eye, blepharitis, conjunctivitis, proptosis of the globe, entropion, uveitis |

Neomycin sulfate, Polymyxin B sulfate, Dexamethasone solution and ointment | Commonly used | Any condition in which corticosteroid use is contraindicated |

| Neomycin sulfate, Hydrocortisone acetate solution and ointment | |||

| Neomycin sulfate, Zn bacitracin, Polymyxin B sulfate, Hydrocortisone ointment | Commonly used | ||

| Neomycin sulfate, Polymyxin B sulfate, Hydrocortisone solution | |||

| Neomycin sulfate, Prednisolone solution & ointment | |||

| Neomycin sulfate, Dexamethasone phosphate solution | |||

| Neomycin sulfate, Methylprednisolone ointment | |||

| Chloramphenicol, Hydrocortisone acetate solution | Commonly used | ||

| Chloramphenicol, Prednisolone acetate ointment | |||

| Gentamicin with Betamethasone | Commonly used | ||

| TOPICAL NON-STEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY

USE: Reduce inflammation and pain INDICATIONS: Uveitis, cataract surgery, panophthalmitis, corneal ulcers |

Flurbiprofen | May delay corneal healing | |

| Suprofen | |||

| Diclofenac | |||

| IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE DRUGS

USE: Suppress the immune response INDICATIONS: Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, corneal ulceration associated

with keratoconjunctivitis sicca, nodular granulomatous episclerokeratitis,

unresponsive uveitis |

Cyclosporine | Drug of choice for keratoconjunctivitis sicca | |

| Azathioprine (systemic) |

Use with extreme caution - potentially toxic to liver and bone marrow | ||

| MYDRIATICS

USE: Dilation of the pupil (mydriasis), control ciliary spasm and the accompanying pain which causes eyelid spasm, photophobia, and lacrimation INDICATIONS: Non-surgical treatment of axial leukoma (white spot on cornea) and axial cataracts. Preoperative mydriasis for cataract surgery and

other ocular surgery, corneal abrasions, corneal ulceration, keratitis,

anterior uveitis, possibly proptosis of the globe. |

Atropine sulfate | Not for routine eye examination | May compromise tear production. May predispose to local irritation. Contraindicated in glaucoma or in animals predisposed to glaucoma. |

| Tropicamide | Short-acting - used for eye examinations | ||

| Phenylephrine HCL | Combined with atropine | ||

| MIOTICS

USE: Cause contraction of the pupil, enhance aqueous outflow INDICATIONS: Keep luxated lens in posterior chamber, treat glaucoma |

Demecarium bromide | Cholinesterase inhibitor, do not use with organophosphate insecticides | |

| Pilocarpine | May irritate the eye | ||

| Carbachol | All miotics are contraindicated in glaucoma secondary to anterior uveitis | ||

| ADRENERGICS

USE: Lower intraocular pressure. Control capillary bleeding during surgery INDICATIONS: Control/treat glaucoma |

Epinephrine | Adrenergic agonist/increases outflow of aqueous humor | |

| Timolol maleate | Beta blocker/ Reduces aqueous formation | ||

| CARBONIC ANHYDRASE INHIBITORS

USE: Decrease aqueous humor production INDICATIONS: Control/treat glaucoma |

Acetazolamide (given orally) |

May cause metabolic acidosis and electrolyte imbalances | |

| Methazolamide (given orally) |

|||

| Dichlorphenamide (given orally) |

Use with caution in animals with sulfonamide sensitivity | ||

| Ethoxzolamide (given orally) |

|||

Summary: The eye is a complex structure that processes images for transfer to the brain. It is composed of several interrelated structures. A problem that affects any portion of the eye can result in loss of vision. A problem that affects one portion of the eye may also affect adjacent structures. Because different disease processes can cause the same signs in the eye, examination by a veterinarian is necessary for proper diagnosis and treatment. Prompt examination and treatment can prevent severe, progressive disease and loss of vision. Animals should be examined by the veterinarian at the first sign of any eye discomfort or abnormality.