A714

Reproduction Management -

Estrus Synchronization and Heat Detection

prostaglandins | GnRH-PGF2a

based synchronization protocols | follicular

waves | ovsynch | heatsynch

| presynch | select synch | MGA-PGF2a

system | CDIRs (the eazi-breed) | heat

detection

Estrus Synchronization:

If a decision is made to artificially inseminate (AI) animals in the herd, a

significant effort needs to made in estrus synchronization and heat detection.

Failure to properly address each of these management issues will result in

failure of the artificial insemination (AI) program.

It is still possible to maintain good reproductive performance in dairy herds

without estrus synchronization, but it requires a SOUND HEAT DETECTION PROGRAM. Unfortunately, maintaining an efficient heat detection program and

quality heat detection personnel can be a never-ending challenge in today's

expanding herds. As the accuracy and efficiency of estrus detection declines,

the value of incorporating estrus synchronization into the reproductive

management program increases proportionately. By grouping cows that calve within

a 1-2 week window, programmed breeding allows producers to systematically

synchronize and inseminate animals for maximum pregnancy rates with minimal

labor inputs. Although it is easy to get confused by the variety of systems

available, this variety provides extraordinary flexibility in developing

tailor-made reproductive management programs.

Estrus Synchronization Programs:

- Prostaglandins: The foundation of any dairy cow synchronization

program is prostaglandin. Prostaglandin F

2a

(PGF2a)

is a naturally occurring hormone. During the normal estrous cycle of a

non-pregnant animal, PGF2a

is released from the uterus 16 to 18 days after the animal was in heat. This

release of PGF2a

functions to destroy the corpus luteum (CL). The CL is a structure in the

ovary that produces the hormone progesterone and prevents the animal from

returning to estrus. The release of PGF2a

from the uterus is the triggering mechanism that results in the animal

returning to estrus every 21 days. Commercially available PGF2a

(Lutalyse, Estrumate, Prostamate, In-Synch) gives the herd owner the ability

to simultaneously remove the CL from all cycling animals at a predetermined

time that is convenient for heat detection and breeding. The major limitation

of PGF2a

is that it is not effective on animals that do not possess a CL. This includes

animals within 6 to 7 days of a previous heat, prepubertal heifers, and

postpartum anestrous (not cycling) cows. Despite these limitations,

prostaglandins are the simplest method to synchronize estrus in cattle.

The PGF2a-based

breeding program requires a set-up

injection of PGF2a

14 days prior to the end of the voluntary waiting period (VWP), followed by

another injection at the end of the VWP. Animals are inseminated to detected

estrus over the next 5 days. Animals not inseminated following the first

injection are re-injected 14 days later and observed for estrus for another 5

days (Figure #1).

Figure #1:

There are four categories of eligible cows that should receive the PGF2a

injection:

- All open cows that are approaching or are just past the voluntary

waiting period (VWP = 45-60 days following calving in most herds).

- Cows not responding to the previous prostaglandin injection. (Animals

not responding to three successive injections should be checked by the

veterinarian for cyclicity.)

- Inseminated animals that have been diagnosed open by palpation.

- Early postpartum cows. Early postpartum injections have therapeutic

benefits in helping cows with low-grade uterine infections to clean.

Additionally, "short cycling" cows with prostaglandin may help to

improve the fertility of subsequent heat cycles. Prostaglandin given two

weeks prior to the VWP will also increase the percentage of animals in the

proper stage of the cycle to respond at the first breeding injection.

Injection Frequency: The

frequency of injections will vary depending on herd size and other management

factors. Prostaglandin programs work by allowing producers to systematically

schedule reproductive management procedures into a short time period for

"groups" of eligible cows. While large herds (> 400 cows) may have

dozens of eligible cows each week, smaller herds (< 60 cows) may only have 1

or 2 eligible animals. Therefore, smaller herd owners may choose to inject

groups of cows at 2 or 3 week intervals, while larger herd owners will inject

weekly.

The key to any of these programs is to

choose a specific day of the week for injections that will complement labor

availability for heat detection and breeding, and to inject all eligible cows on

each injection day regardless of the number of weeks since the previous

injection. This facilitates simplicity and minimizes confusion.

Although historic recommendations were to

inject PGF2a

at 11-day intervals, from a scheduling consideration, the 14-day interval is

much easier to implement. The second injection is always 2 weeks down on the

calendar from the first, and all activities (injections, heat detection,

breeding) are conducted on the same days of the week from one week to the next.

Additionally, when using the 11-day interval, animals that respond to the

first injection but are not detected in estrus will be between day 7 and 9 of

the cycle at the next injection. These "early" CLs typically do not

respond to PGF2a

as well as older, more mature ones. Using a 14-day interval, a missed heat from

the first injection will be on days 10 to 12 of the cycle at the second

injection. This 3-day difference significantly improves the probability of the

animal responding again.

Advantages of Prostaglandin Programs:

- Improved Heat Detection: A major benefit of prostaglandin programs

is to group cows so they all come into heat at the same time. This facilitates

more efficient use of labor for heat detection. Mounting activity also increases

two-to-four fold with multiple cows in heat. Thus, not only can time and labor

be focused to a period when cows should be in heat, but the cows are also more

willing to display the many signs associated with estrus. During such active

periods, many naturally cycling cows are likely to be detected that otherwise

would have gone unnoticed.

- Reduced Days to First Service: The more efficient a producer is at

detecting heat, the greater the impact on "days to first service."

However, prostaglandin programs also have a more direct impact on this variable.

With a voluntary waiting period of 60 days between calving and breeding, the

average days to first service would typically be around 70 days (if all cows

cycled and were detected during that 21 day period). In a herd on a

prostaglandin program, responding animals are generally inseminated 3-4 days

after each injection. Thus, on average, days to first service are cut by about 7

days for each responding animal.

- Possible Increased Conception: Most herds on a prostaglandin

program have experienced increased conception rates. Prostaglandin has no direct

effect on fertility; however, better heat detection results in fewer cows

getting bred when they are not actually in heat.

- Allows a Greater Focus on Cyclicity: Organized prostaglandin

programs "force" producers to focus more attention on the cyclicity of

their herds. Any non-cycling cow on the program will be diagnosed as a problem

within 2-3 weeks of her VWP. A producer can then seek veterinary intervention

early to get her back on track. Equally important is the fact that the cows that

are cycling and healthy get inseminated early. These are the cows that make

money for an operation.

- Flexibility: Some producers limit the number of animals bred during

the warm summer months. In the fall and winter, cows may be injected weekly.

Gradually back the program off to once every 2 weeks or 3 weeks as a higher

percentage of the herd becomes pregnant. In the spring, prostaglandin programs

can be used to get more animals pregnant before the summer breeding slump

arrives.

For producers investigating seasonal dairying, a synchronization program such

as this is a must. To have a strict milking season, there must be a strict

calving season which dictates a strict breeding season.

- The program is simple and easy to schedule and administer.

- It is the least expensive of all popular synchronization programs.

Disadvantages and Precautions:

- Possible Abortions: Prostaglandin programs require accurate

identification of cows and excellent record keeping systems. Because they may

abort, a producer must be certain that previously inseminated or pregnant cows

are not mistakenly injected with prostaglandin.

- No Fixed-time AI: Although prostaglandin labels may recommend

breeding cows at 80 hours after the injection, this is not conducive to

optimum fertility. Breeding at 80 hours may be implemented to help settle some

cows that are hard to catch in heat; however, it should not be used as

standard practice on all cows. Considerable variation exists in the interval

from PGF

2a

injection to estrus; therefore, PGF2a

alone is not conducive to fixed-time AI. Additionally, breeding an animal at

80 hours without observation of standing estrus closes the door on all

reproductive management options until the animal returns to estrus or is

palpated for pregnancy. If the animal was not cycling, this could be a costly

mistake. It is best to inseminate cows based on observation of standing

estrus when using prostaglandin.

Daily Heat Detection: Although prostaglandin programs allow

producers to focus heat detection during a short period of time, some heat

detection should be done each day to detect naturally cycling animals and

possible returns to estrus of previously inseminated animals.

It is not effective on early cycle or anestrous animals.

GnRH-PGF2a

Based Synchronization Protocols: Numerous

new synchronization protocols currently recommended for cows use gonadotropin-releasing

hormone (GnRH) in conjunction with PGF2a.

A naturally occurring hormone, GnRH is more popularly known by the commercial

brand names of Cystorelin, Factrel, and Fertagyl.

Each GnRH-based protocol uses the same basic framework, which involves an

injection of GnRH, followed 7 days later with an injection of PGF2a.

The way animals are subsequently handled for heat detection and breeding is

where the protocols begin to vary. To understand the benefits of GnRH-based

synchronization protocols and how they work, an understanding of the concept of

follicular waves in cattle must be gained. The following is a brief description

of follicular waves in cattle.

- Follicular Waves: Follicles are blister-like structures that grow

on the ovaries. Each follicle contains an unfertilized egg that will be

released if the follicle ovulates. Research has revealed that follicular

growth occurs in waves throughout the estrous cycle and that 2-3 follicular

waves may occur during an 18-24 day cycle. Each wave is characterized by rapid

growth of numerous small follicles. From this wave of follicles, one follicle

is allowed to grow to a much larger size than the others (12-15 mm). This

large follicle is called the dominant follicle because it has the ability to

regulate and restrict the growth of other smaller follicles. A few days after

reaching maximum size, the dominant follicle begins to regress. As the

dominant follicle regresses, it begins to lose the ability to restrict the

growth of other follicles. Thus a new follicular wave is initiated coinciding

with the regression of the previous dominant follicle. From the new follicular

wave, another dominant follicle will be selected.

Any dominant follicle has the capacity to

ovulate provided the inhibitory effects of progesterone can be removed at an

opportune time. Prostaglandins serve this function by destroying the CL;

however, PGF

2a

has no direct effect on the normal pattern of follicular waves. Thus the stage

of follicular development at the time of PGF2a

injection will affect the interval from injection to standing estrus. Animals

injected when the dominant follicle is in the growing phase will display estrus

within 2 to 3 days; whereas, animals with aged or regressing dominant follicles

may require 4 to 6 days before a new follicle can be recruited for ovulation.

Thus the interval from PGF2a

injection to estrus and ovulation is highly variable between cows due to

differences in the stage of follicular development at the time of PGF2a

injection.

Follicular Waves and GnRH: An injection of GnRH causes a release of

luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary gland in the brain. This LH

"surge" results in ovulation or luteinization of most large dominant

follicles. A new "synchronized" follicular wave is initiated in these

animals 2 to 3 days later. Because GnRH stimulates development of luteal tissue

in place of the dominant follicle, a higher percentage of cows will possess

sufficient luteal tissue to respond to PGF2a

7 days later. Injecting cows with PGF2a

7 days after a GnRH injection synchronizes luteal regression in animals with

previously synchronized follicular development. The result is a higher estrus

response rate and much tighter synchrony of estrus when compared to PGF2a

alone.

Although GnRH synchronizes follicular development in most cows, some cows do

not respond to the first GnRH injection. If the GnRH injection fails to

luteinize a follicle in animals that were due to show heat naturally around the

time of the PGF2a

injection, the treatment fails to prevent those animals from displaying estrus.

Research in both beef and dairy cows has consistently revealed that 5 to 10%

of cows treated with GnRH will display standing estrus 6 to 7 days later. These

natural heats should be bred when detected, and subsequent injections are not

administered. Because virgin heifers do not respond to GnRH injections as

consistently as mature cows, use of GnRH-based synchronization protocols is not

currently recommended.

GnRH-PGF2a

Based Synchronization Options:

- Ovsynch: Ovsynch is a fixed-time Al synchronization protocol that

has been developed, tested, and used extensively in dairy cattle. It has also

proven to be a reliable timed Al program for beef cows. The protocol builds on

the basic GnRH-PGF

2a

format by adding a second GnRH injection 48 hours after the PGF2a

injection (Figure #2). This second GnRH injection induces ovulation of the

dominant follicle recruited after the first GnRH injection. All cows are mass

inseminated without estrous detection at 8 to 18 hours after the second GnRH

injection.

Figure #2:

Across large numbers of dairy cattle, pregnancy rates to Ovsynch generally

average in the 30 to 40% range. Although these numbers may not appear impressive

at first, it is important to understand them in terms of an applied reproductive

management program. Records from DHIA processing centers suggest that the

average dairy producer only detects 50% of the heats in his/her herd and then

only gets 40 to 50% of the inseminated animals to conceive. Thus, in a 21 day

period, the effective pregnancy rate in the average dairy herd is approximately

25% (50% detected in heat x 50% conception = 25% pregnant). In that context, a

30 to 40% pregnancy rate to a single fixed time Al without heat detection is

quite acceptable.

Recent research suggests Ovsynch pregnancy

rates in dairy herds can be significantly improved if cows are set-up or

"pre-synchronized" to be in the early luteal phase of the estrous

cycle at the time of the first GnRH injection. This can be accomplished with 2

injections of PGF2a

given at 14-day intervals, with the last injection administered 14 days prior to

starting Ovsynch. This option is particularly amendable in dairy herds that

routinely administer therapeutic injections of PGF2a

during the early postpartum period.

Although Ovsynch allows for acceptable

pregnancy rates with no heat detection, it does not eliminate the need for heat

detection. Ovsynch treated animals should be observed closely for returns to

estrus 18 to 24 days later. Additionally, natural heats can occur on any given

day and Select Sires' research has found that as many as 20% of treated dairy or

beef cows will display standing estrus between days 6 and 9 of the Ovsynch

protocol. Conception rates in these animals will be compromised if bred strictly

on a timed Al basis.

Heatsynch: Because

ECP has been taken off the market, this protocol is currently not feasible.

Heatsynch

is a newly developed synchronization protocol that uses the less-expensive

hormone ECP in place of the second GnRH injection of the Ovsynch protocol.

However, because of differences in how these hormones work, there also are

several important differences in protocol implementation. ECP is a commercially

available form of the natural hormone, estrogen. Estrogen is the hormone that

causes cows to show the many signs of heat when they come into estrus, and it

creates a surge-type release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the

brain. GnRH, in turn, causes the release of luteinizing hormone (LH), which

results in ovulation of the mature follicle. GnRH is the hormone that is used to

induce ovulation in the Ovsynch protocol discussed previously.

To induce ovulation, an LH

surge must be induced. GnRH has a direct and almost immediate effect on the

release of LH, while ECP has a delayed effect. A recent study found that cows

injected with GnRH have an LH surge within about an hour, while the LH surge of

ECP treated cows was not detected for about 41 hours. This difference in time to

LH surge means the hormone injection intervals must also be altered when

substituting ECP for GnRH. Both Ovsynch and Heatsynch call for a GnRH injection,

followed 7 days later with a PGF2a

injection. Heatsynch then

prescribes a one-milligram injection of ECP 24 hours later, while Ovsynch-treated

cows receive GnRH 48 hours later. Because of the delayed interval to the LH

surge, the interval to fixed-time AI is 72 hours after PGF2a

(48 hours after ECP) for Heatsynch, compared with 56-64 hours after PGF2a

(8-16 hours after GnRH) for Ovsynch.

The biggest difference

that producers will immediately notice between Heatsynch and Ovsynch is the

percentage of cows that will show visual signs of estrus. ECP stimulates estrus

expression following injection. Heatsynch cows detected in estrus should be bred

according to the "a.m./p.m. rule" or at 72 hours after PGF2a,

whichever comes first. In contrast, the

second GnRH injection of Ovsynch induces the LH surge and ovulation almost

immediately, shutting down estrogen production from the growing follicle and

thus, very few cows will show heat even though they are ovulating.

The increased estrous activity from Heatsynch certainly makes producers and

technicians feel better about breeding cows, but that does not necessarily mean

it is a better synchronization protocol. In one study, even though 40 percent of

Heatsynch cows were detected in estrus compared to only 8 percent for Ovsynch,

only 59 percent of Heatsynch cows ovulated following PGF2a

injection compared to 83 percent for Ovsynch. Additionally, some producers have

found this increased estrous activity of Heatsynch is not necessarily a plus if

footing surfaces are less than optimal. This is particularly important to

remember during the icy winter months.

Cows that show heat almost always will have better conception rates than

those that do not. However, controlled studies directly comparing Heatsynch and

Ovsynch basically indicate the two have achieved identical overall pregnancy

rates. The major advantages of Heatsynch compared to Ovsynch are reduced hormone

costs, more efficient use of expensive semen in higher conception-rate cows that

are allowed to express estrus, and somewhat easier scheduling and

implementation, since all injections and AI are at 24-hour intervals.

Presynch: Presynch uses 2 injections of PGF2a

at 14 day intervals to pre-synchronize most of the cycling animals. Fourteen

days after the 2nd PGF2a

injection, these cows will be in the proper stage of the estrous cycle to

respond to the first GNRH injection in the Select Synch, Heatsynch, or Ovsynch

system. Preliminary results using Presynch in front of Ovsynch suggests

pregnancy rates were improved by 10-20 percent. In many herds, therapeutic use

of PGF2a

in the early postpartum period is standard practice; Presynch simply coordinates

this use of PGF2a

for optimum results with a GnRH-based breeding protocol. Also, Presynch should

eliminate most early heats.

Select Synch: With the Select Synch system, cows are injected with

GnRH and PGF2a

7 days apart (Figure #3). Heat detection begins 24-48 hours before the PGF2a

injection and continues for the next 5-7 days. The PGF2a

injection is excluded for cows detected in estrus on day 6 or 7. Animals are

inseminated 8 to 12 hours after being observed in standing estrus.

An alternative method of using the Select Synch program, sometimes called the

Hybrid system (combination of Select Synch and Ovsynch), is to heat detect and

Al until 72 hours after the PGF2a

injection and then mass-Al and give GnRH to those cows that have not exhibited

estrus.

Figure #3:

When comparing estrus response, conception

and pregnancy rates for Select Synch and the two-shot PGF2a

system in cows, Select Synch resulted in more cows in standing estrus, equal or

better conception rates, and ultimately more cows pregnant during the

synchronized breeding period. These benefits are particularly evident in

anestrus cows. The Select Synch system can more than double the percentage of

anestrous cows that become pregnant during the synchronized breeding period.

Major benefits of the Select Synch system

are simplicity and tighter synchrony of estrus. Most animals will display

standing estrus 2 to 4 days after the PGF2a

injection. Overall, estrus response rates in well-managed herds average

approximately 70 to 75% with no adverse effect on conception rates (60 to 70%),

resulting in synchronized pregnancy rates that average between 45 and 50%.

Select Synch followed by heat detection

and 72 hour fixed-time Al is an option that allows producers to maximize

potential pregnancy rates while minimizing labor requirements for estrus

detection. Heat detection is used to catch the early heats and to breed the

majority of the group (60-70%) to standing heats. Estrous detection can be

terminated at 48-60 hours after PGF2a,

followed by mass-Al of the non-responders at 72 hours with GnRH. This option

gives all cows an opportunity to conceive and, compared to strict fixed-time Al

options such as Ovsynch, drug costs are reduced because only 30 to 40% of the

group will receive the second GnRH injection. Additionally, if less than 40-50%

of the group is detected in estrus by 72 hours, the mass mating can be aborted,

saving drugs, money, and semen that might be wasted on anestrous cows.

MGA - PGF2a

System: The MGA-PGF2a

system (Figure #4) is a time tested, proven method for synchronizing estrus in

dairy heifers. MGA is not approved for use in lactating dairy animals.

Metengestrol Acetate (MGA) is a synthetic form of the naturally occurring

hormone, progesterone. For best results, mix MGA with 3 to 5 lbs. of a grain

supplement and feed at a rate of 0.5 mg/head/day for 14 days. Top-dressing or

mixing MGA in a ration can work, but intake (and thus results) tends to be more

variable.

Within 3 to 5 days after MGA feeding, most heifers will display standing

heat. DO NOT BREED at this heat because conception rates are reduced. Wait 17 to

19 days after the last day of MGA feeding and inject all heifers with a single

dose of PGF2a.

For the next 5 to 7 days, inseminate animals 8 to 12 hours after detected

estrus. Although the MGA-PGF2a

system has traditionally used a 17-day interval between MGA feeding and the PGF2a

injection, recent research suggests a 19-day interval results in slightly higher

response and synchrony of estrus.

Figure #4:

Success of the MGA system depends on

adequate bunk space and proper feeding rates so the appropriate daily dosage is

consumed by each heifer. In addition to stimulating cyclicity in many

prepubertal and anestrous animals, researchers at the University of Kentucky

found the MGA-PGF2a

system to result in higher estrus response and conception rates when compared to

synchronization using PGF2a

alone. With good heat detection of well-managed heifers at the proper age,

weight, and body condition, synchronized pregnancy rates of 50-70% can be

achieved. Because the synchrony of heats following the MGA-PGF2a

protocol can be variable, pregnancy rates to single, fixed time inseminations

are also variable. However, very acceptable pregnancy rates (45 to 55%) have

been achieved to a single insemination at 72 hours or by double inseminating at

60 and 96 hours following the PGF2a

injection. On average, timed Al with this system will often result in a 5 to 10%

(or more) reduction in pregnancy rates relative to what is possible with heat

detection and breeding to standing heats.

CIDRs (The Eazi-Breed): The Eazi-Breed CIDR

(Controlled

internal drug-releasing device)

cattle insert, or CIDR

as it is most commonly called, is the newest synchronization product available

in the U.S. market. Developed and used extensively in New Zealand and marketed

in the United States by Pharmacia Animal Health, the CIDR is a vaginal insert

that delivers the natural hormone progesterone throughout the 7-day implant

period. This progestin stimulation helps to induce cyclicity in anestrous cows

and advances puberty in heifers. In studies that used an injection of

prostaglandin (Lutalyse) on day 6 after insertion and implant removal on day 7,

research has shown the CIDR to be an effective means of synchronizing estrus in

virgin beef and dairy heifers, and in postpartum beef cows. The CIDR is now

approved for use in lactating dairy cattle.

Animals may either be bred to detected estrus for three or four days after

CIDR removal or fixed-time inseminated at 48 to 54 hours after implant removal.

Although labeled for a day 6 prostaglandin (Lutalyse) injection, practical

implementation in most other countries usually involves moving the prostaglandin

(Lutalyse) to day 7, which eliminates one animal handling with no indications of

reduced efficacy.

Although the rumors of 90 percent estrous-response rates are true, these are

exceptions and not the averages. One of the studies that was used to demonstrate

efficacy for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval showed that

although pregnancy rates in excess of 50 percent are certainly possible, data

suggests that even when working with the improbable case of 100 percent

cyclicity, pregnancy rates in excess of 50 percent are not guaranteed. Numerous

other studies have evaluated the use of the CIDR within the Ovsynch protocol

(e.g., insert CIDR and inject GnRH; remove CIDR and inject prostaglandin (Lutalyse)

7 days later). Most of these studies suggest improved reproductive performance

in animals using the CIDR approach.

Reusing CIDRS: The following are a few reasons not to reuse a CIDR:

Aside from legal issues, there are no studies available to document the efficacy

of a used CIDR to induce cyclicity. In fact, the U.S. version was

designed to have minimal residual progesterone upon removal, which would suggest

they would not be effective if reused. Last, but certainly not least, regardless

of how they are cleaned, the sanitation of a used CIDR is compromised and reuse

increases the risk of disease transmission within the herd.

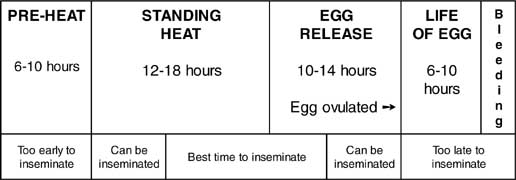

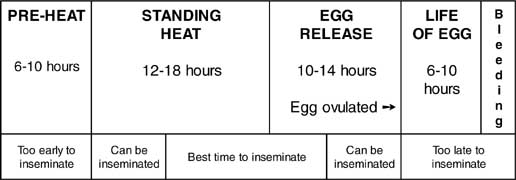

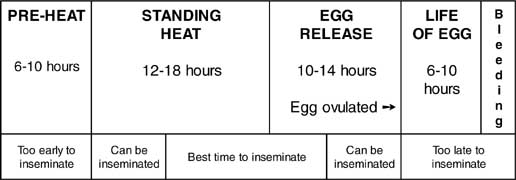

Heat Detection:

A cow in heat is one that is receptive to the bull or ready to be

artificially inseminated. This time usually occurs every 18-24 days and lasts

for 12-18 hours. Most cows should be bred 8-12 hours after being observed in

standing estrus. The following table demonstrates part of a cow’s estrous

cycle and when the proper time to inseminate a cow occurs.

This list identifies various signs a cow shows when she is in heat:

- She will stand and let another cow mount or ride her (this is the most

reliable indicator of heat). Realize that the cow being ridden is the one in

"standing heat."

- This cow may ride other cows.

- She may become nervous and restless.

- She can have a roughened tail head from being ridden.

- This cow can have a clear, mucus discharge from the vulva.

- She may have a swollen vulva.

It is important to physically observe the herd or group of animals at least

twice a day. This is because most cows show signs of heat in the morning (6 a.m.

to noon), evening (6 p.m. to midnight), or during the night. In fact, most

animals (approximately 45%) show heat during the hours of midnight to 6 a.m.

Because heat detection is often difficult, the following are tools a producer

can use to help identify animals that are in heat:

- A chin-ball marker - This device is placed under the chin of a detector

animal. When the animal mounts, the device leaves a mark on the back of the

animal being ridden.

- Androgenized cows - These are female cows that are given testosterone to

cause them to show male-like behavior. These animals are great candidates for

the chin-ball marker.

- Surgically altered bulls - These animals are surgically altered in a way

that prevents the penis from entering the cow. These bulls still have the

sexual drive to mount, but cannot reproduce.

- Tail-head devices (Kamar) and paint - These devices are glued onto the

tail-head of the cow. Pressure on the device when the cow is mounted, causes

the marker to change color. In the case of the Kamar device, the white marker

changes to red when the cow is ridden. Paint sticks can also be used in a

similar manner. The paint can be applied in areas on the hooks, pins and

tail-head. When the cow is ridden, the paint will rub-off and smear.

* None of these methods can replace physical observation!

All of the graphs and most of the text were used with permission from Select

Sires, Plain City, OH 43064. Phone # 614-873-4683.