E406

Joint, Tendon, Ligament, Bone, and Foot Problems

foot | pastern

and fetlock | canon bone regions

| knee and upper front limb | hock

| stifle and upper hind limb | neck

region | different joints and

locations | nutrition and supplements

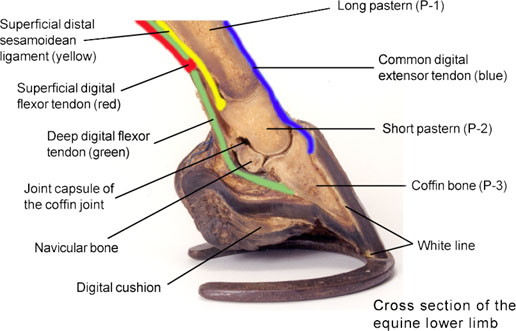

Introduction:

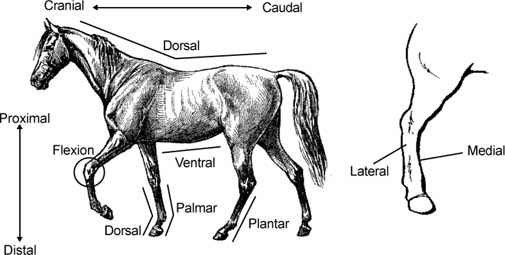

Today’s horse is a

highly trained athlete that is often pushed to the very limits. Because of this,

tendon, bone, hoof, and joint problems are some of the most common injuries many

horse owners encounter. One of the keys to identifying and then treating these

problems is understanding the terms and anatomical structures that may be

involved. Another key is understanding the function of certain tendons,

ligaments, and bones. To help understand these structures and their function,

the pictures and captions on pages A28, A30, and

A35 are essential. The

following diagrams and definitions are also of benefit.

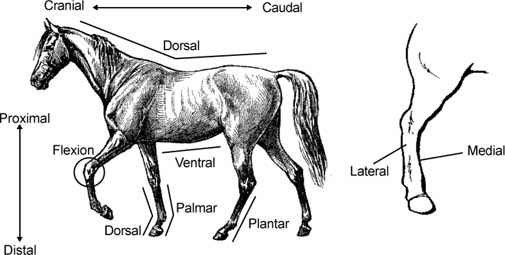

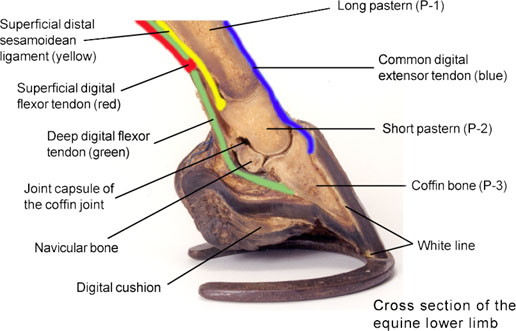

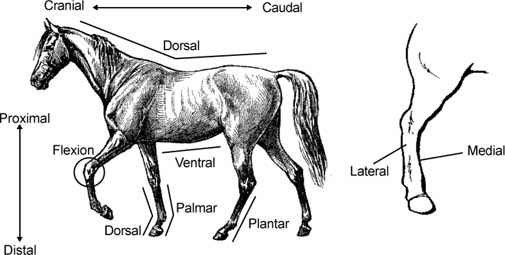

Terms:

- Cranial - Describing something that is closer to the head. For

example, the withers are cranial to the tail.

- Caudal - Describing something that is closer to the tail. For

example, the withers are caudal to the neck.

- Dorsal - Something that is away from the ground or the front

surface of the limb below the knee or hock. For example, the withers are dorsal to the

heart.

- Ventral - Something that is towards the ground. For example, the

udder of a mare is found on the ventral portion of the abdomen.

- Palmar - Describing the back surface of the front limb below the

knee. It is opposite the dorsal surface.

- Plantar - Describing the back surface of the hind limb below the

hock. It is opposite the dorsal surface.

- Proximal - Describing something that is closer to the main part of

the body. For example, the knee (carpus) is proximal to the fetlock.

- Distal - Describing something that is further away from the main

part of the body. For example, the fetlock is distal to the knee (carpus).

- Medial - Something that is towards the middle of the body or limb.

The medial surface of the limb is towards the inside.

- Lateral - Something that is away from the body or limb. The

lateral surface of the limb is towards the outside.

- Deep - Describing something that is farther from the surface. For

example, the cannon bone is deep to the skin surface.

- Superficial - Describing something that is closer to the surface.

For example, the skin is superficial to the gluteal muscles.

- Tendon - A tendon is a fibrous cord that attaches muscle to bone.

Tendons are used to flex and extend each joint when a muscle or group of muscles

contracts. Some of the most common tendons that can be injured in the horse are

the flexor tendons (superficial and deep flexor tendons) in the distal and

palmar/plantar areas of the front and hind limbs.

- Ligament - This is a band of fibrous tissue that connects bone and

cartilage. It is often referred to as the connection from bone to bone.

- Joint - The place where two or more bones of the body join.

- Cartilage - A specialized connective tissue that is found on the

ends of bones that form part of a joint.

- Synovial Membrane - The inner lining of the joint capsule or

tendon sheath that contains the synovial or joint fluid.

- Synovitis - Inflammation of the synovial membrane.

- Arthroscope/arthroscopic Exam - An arthroscopic exam is a

procedure where a specialized instrument called a arthroscope is inserted into a

joint. The arthroscope is a long slender instrument with a fiber optic camera on

the end of it that transmits a picture to a viewing screen.

- Arthritis - This means inflammation of a joint. The inflammation

can be caused by injury, degeneration, or infection.

- Physis/physitis - The growth plate of a bone. When it becomes

inflamed, it is called physitis.

- Epiphysitis - In specific terms, this relates to inflammation of

the end of a long bone. There is a disease called epiphysitis that is actually a

problem with the growth plate.

- Bone - The hard form of connective tissue that makes up most of

the skeleton.

- Degenerative Joint Disease (Osteoarthritis) - Degenerative joint

disease (DJD) is the final outcome of many different problems that occur in the

joint. A joint with DJD has destructive changes in the cartilage, bone, and

tissues. These changes can be caused by arthritis, synovitis, injury,

osteochondritis, fractures, etc.

- Osteochondritis - Inflammation of both bone and cartilage.

- Periosteum - Specialized connective tissue that covers the bones

in the body. It is essential for proper bone growth and continued bone support.

- Ankylosis - When a joint is made immovable by disease, injury, or

surgical procedure.

- Arthrodesis - When a joint is surgically fused/joined to prevent

movement.

Diagnosing a Problem:

Many times it is

obvious that an injury has occurred. Other times the injury may be old, or the

horse may not be showing significant signs of lameness. The suggestions,

pictures, and information found on pages B885 and

E460 can help a horse owner

identify a lameness problem.

The following information will identify the specific tendon, ligament, joint,

bone, and foot problems that are common in horses. For the most part, the

information will be broken down into sections based on anatomical location of

where the problem is occurring. For example, all problems associated with

fetlock will be discussed together in alphabetical order. A general category is

found towards the end that contains problems that can be found in many different

joints or locations. Details on the cause, clinical signs, diagnosis, and

treatment of each problem will be included as needed. A brief discussion on the

role of nutrition and supplements in bone and joint problems is also found at

the end of the discussion.

Note: The following reference has been used extensively to generate much of

the information contained in this discussion: Ted S. Stashak, DVM, MS. Adams’

Lameness in Horses. Lea and Febiger, 1987.

Problems with the Foot

- Abscesses, Bruising, and Puncture Wounds:

Causative Agents: Foot abscesses are pockets of infection that occur

under the sole or hoof. They can be caused by bruising from rocks or hard

objects that impact the sole of the foot. If the bruising is severe, the

sensitive tissues can die (necrose) and an abscess will result. Abscesses can

also occur with laminitis and puncture wounds.

Clinical Signs: These horses are often lame on the affected limb and

are sensitive to hoof testers in the injured area. Areas of heat may also be

noted in the foot. If the abscess is open, it will have some discharge (either

serum or infection). In many cases the outer surface of a bruise or abscess can

be removed with a hoof knife, revealing red staining (hemorrhage) in the

underlying tissues. If the problem is caused by a puncture wound, a tract or

maybe even the nail or other object can be seen. If the nail is still in place,

it is best not remove it until a veterinarian can examine the extent of the

puncture with a radiograph (X-ray). If the abscess or infected puncture wound

does not have a place to drain, it may "break out" at the coronary

band. This appears as an open wound, draining infectious material.

Treatment: The outer surface of an abscess must be removed to allow

draining and any bruised tissue should be removed. Puncture wounds should also

be explored and any associated abscess drained. If the puncture wound involves

any bone or joint structures, extensive treatment involving flushing, surgical

draining, and antibiotics are required. Sometimes portions of the hoof wall need

to be removed to allow adequate draining. (This requires training and sometimes

special equipment.) Once the abscess/puncture wound is opened and clean, the

foot should be soaked on a daily basis in a solution of dilute betadine or epsom

salts for 10-15 minutes. After soaking, antiseptic (betadine) ointment should be

applied to the draining wound, a gauze pad placed over the area, and the foot

wrapped to prevent additional contamination. Covering the bottom of the foot

with duct tape can help reduce the contamination and keep the bandage in place.

Keeping the foot clean and dry is a must until the injury has healed. Giving the

horse a tetanus shot, particularly if a puncture wound is involved, is

important. It is best to rest these animals from any strenuous work until

adequate healing takes place.

Corns:

Causative Agents: Corns are caused by pressure placed on the wall and

sole of the foot in the heel regions. This pressure can come from improper

shoeing or by letting the feet get too long with the shoe in place.

Clinical Signs: These horses are often lame on the affected limb and

are sensitive to hoof testers in the heel area. The corn can be dry or have some

discharge (either serum or infection). In many cases the outer surface of the

corn can be removed with a hoof knife, revealing red staining (hemorrhage) in

the underlying tissues.

Treatment: If the problem has been caused by improper shoeing,

removing the shoe is a must. If the corn has some discharge, the outer surface

of the corn must be removed to allow draining and any bruised tissue should be

removed. Once the corn is drained, the foot should be soaked on a daily basis in

a solution of epsom salts for 10-15 minutes. After soaking, betadine ointment

should be applied to the corn area and the foot wrapped to prevent additional

contamination. Covering the bottom of the foot with duct tape can help reduce

the contamination. Keeping the foot clean and dry is a must until the injury has

healed. If the horse must be used, a bar type shoe should be put on the foot.

These types of shoes help to distribute the horse’s weight evenly around the

foot and to the frog, reducing the amount of pressure placed on the heel

regions. If necessary, the corn should be trimmed away to avoid contact and

pressure with the shoe.

Dry Hoof Wall:

Introduction and Recommendations: The amount of moisture in the hoof

wall is influenced by the environment and the amount of moisture in the ground.

When the environment is dry, with little moisture, the feet can become brittle.

Nutrition can play a role in maintaining healthy feet; if the horse is fed a

balanced diet with appropriate amounts of protein and energy, the feet will not

usually suffer.

General ingredients that keep the foot moist are pine tar, lanolin, fish

oils, and olive oil. Select products in which these are the active ingredients.

Pine tar products seem to be the most effective and generally cost the least.

Other ingredients like ketones, toluene, acetate, and alcohols are commonly

used, but are not as effective.

Fractures:

Causative Agent: Fractures of the coffin bone or P-3 are not very

common. When they do occur, they are often the result of strenuous exercise on

firm or packed ground. A fracture of the extensor process of the coffin bone can

also occur. Extensor process fractures occur when excessive stress is placed on

the common digital extensor tendon or when the coffin joint is placed in severe

extension.

Clinical Signs/Diagnosis: Severe lameness is often noted with

fractures of the coffin bone. This is not so obvious with fractures of the

extensor process. If a fractured extensor process has been a problem for some

time, the foot may actually take on a sort of V-shape. Radiographs are the best

way to diagnose each of these problems.

Treatment: Most fractures of the coffin bone can be treated by placing

on a full bar shoe with quarter clips on both sides. This will help prevent the

expansion of the hoof wall. Strict stall rest for 8-10 months is essential for

complete recovery. The best treatment for a fractured extensor process is

surgical removal or possibly screwing a large fragment back onto the coffin

bone. No matter what procedure is used, strict stall rest is essential for 8

weeks. After this time, the horse should be rested and only hand walked for an

additional 6 months.

Laminitis (Founder) - For a discussion on laminitis, refer to page E465.

Navicular - For a complete discussion on navicular, refer to page E544.

Pedal Osteitis:

Causative Agent and Diagnosis: Repeated and chronic inflammation of

the coffin bone causes this problem. This continued inflammation can be caused

by laminitis, sole bruising, puncture wounds, and corns. The continued

inflammation causes the outside edges of the coffin bone to demineralize. These

areas of demineralization can be seen on radiographs as places where the edges

of the coffin bone look roughened and "moth eaten."

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Lameness is often noted with this

problem of the coffin bone, and the horse can be sensitive to hoof testers in the

toe region.

Treatment: Most cases of pedal osteitis can be helped by using shoes

and padding that keep the sole from impacting the ground. Treating the

underlying problem (laminitis, bruising, etc.) causing the inflammation is also

essential. Rest is necessary for a complete recovery; however, some animals may

never return to full function.

Quittor:

Causative Agent: This problem is caused when an injury takes place

near the coronary band over the areas of the collateral cartilages. The

collateral cartilages are found on either side of the coffin bone of the foot

and extend up past the coronary band. These injuries introduce infection into

the cartilages.

Clinical Signs: Swelling, pain, and heat are often noted over the

coronary band. Draining tracts of infection can often be found above the

coronary band. These horses can be lame early on, but show fewer signs as the

problem progresses.

Diagnosis: Many other problems can also cause draining at the coronary

band (gravel, abscesses). The difference between quittor and these other

problems is the fact that this problem is more extensive and the draining tracts

are often larger and extend deep in the foot. The draining tracts will often

come and go. Radiographs can also be helpful in identifying this problem.

Treatment: Surgical removal of the problem cartilage is the best

treatment. All the draining tracts are also removed. Flushing, soaking, and

antibiotics are continued treatments after the surgery.

Selenium Toxicity - This can cause the hoof wall to crack parallel to

the coronary band in different sections down the hoof wall. Other problems can

also be noted in the coat, mane, and tail. Additional details on selenium

toxicity can be found on E835.

Sheared Heels:

Causative Agents: This condition occurs when there are abnormal forces

applied to one of the heel bulbs. This over use of one of the heels occurs when

improper trimming causes one heel to be left longer than the other. Because one

heel is used more often than the other, a breakdown of the tissues and

structures between the heel bulbs occurs. Horses with long toes and short heels

are also susceptible.

Clinical Signs/Diagnosis: Most horses with sheared heels can be

identified by examining the back portion of the foot. The heel that is left too

long is thrust upwards and has a straighter hoof wall when compared to the

opposite heel (see figure 1). The heel that is not bearing the excessive weight

often has a flared hoof wall. Pain is sometimes noted when the heel bulbs are

pushed in opposite directions. Hoof testers can also be used to identify areas

of pain in the heel regions.

Figure 1

|

|

|

| The

heel on this side is the one bearing most of the weight. It has a straight wall

and the coronary band above this heel is thrust upward. |

|

Treatment: The key to treating this problem is to bring the foot back

into balance by trimming the long heel. Some cases may resolve by simply

trimming and then letting the horse go bare foot. In other cases, the long heel

should be trimmed and a full bar shoe should be used to distribute the horse’s

weight evenly around the foot. With successive trimming and shoeing, the foot

can eventually come back into balance with both heels evenly on the ground

surface. In very severe cases, a normal return to function may not be

achieved.

Sidebone:

Causative Agent: Sidebone is caused by concussion forces being placed

on the collateral cartilages. The collateral cartilages are found on either side

of the coffin bone of the foot and extend up past the coronary band. With

continued traumatic forces, the collateral cartilages begin to turn to bone (or

ossify). Sidebone is usually found in the front feet of horses that have

conformation problems. Animals that are base-narrow or base-wide have the

tendency to develop this problem.

Clinical Signs: Pain and heat are often noted over the collateral

cartilages during the active stages of the disease. The cartilages that are

involved will often be harder than normal and painful to the touch. These horses

may or may not be lame.

Diagnosis: It is often easy to falsely conclude that sidebone is the

cause for a horse’s lameness. Sidebone should not be diagnosed as the cause of

lameness unless there is heat and pain associated with the collateral

cartilages. Radiographs showing the cartilage turning into bone can be used to

identify this problem. This finding alone, however, is not sufficient to

diagnose sidebone without the associated signs of heat and pain.

Treatment: Some farriers recommend that the hoof wall over the

sidebone areas be thinned or grooved. These processes allow the foot to expand

and be more flexible. If fractures of the sidebone occur, they need to be

surgically removed. If pain and heat are still present, treating with

phenylbutazone can help. All cases should be rested until the inflammation has

subsided. In general, many cases are not lame and do not require treatment

unless there is active pain and heat.

Thrush:

Causative Agent: Thrush is caused by an infection of anaerobic bacteria and

potentially other organisms in the frog and sulcus (commissure). These organisms

infect horses that are kept

in moist, dirty environments, where the foot is continually dirty and wet. Feet

that are improperly shod or are improperly trimmed are also at risk of being

infected.

Clinical Signs: In most cases the commissures of the foot are full of a

dark, foul smelling discharge. The commissures are often deeper than normal, and

the frog can be loosened from the underlying tissues. In severe cases the

organisms can be infecting the sensitive structures of the foot causing lameness

and infections going up the limb.

Treatment: The treatment for thrush involves keeping the foot clean, dry,

and properly shod. After the foot is completely cleaned with a hoof pick and

knife, topical medications such as povidone-iodine (Betadine), chlorhexidine, or

Kopertox should be applied on a daily basis until the infection is cleared.

Toe, Quarter, and Heel Cracks (Sand cracks):

Causative Agent: Cracks can start from the bottom or the top of the hoof

wall and extend variable distances. The cracks that start at the coronary band

are usually caused by some type of trauma or injury to the coronary band. The

cracks that start at the bottom of the foot are most often caused by letting the

foot go too long without trimming. Excessive drying of the foot can also make it

more susceptible to cracking.

Clinical Signs: Depending on the severity of the cracks, some horses may

be lame. Some cracks may become infected and discharge blood or pus.

Treatment: The treatment for each crack will depend on its location,

depth, and how far up or down the hoof wall it extends. Any cracks with signs of

infection, should be treated with povidone-iodine (Betadine) and bandaged until

the infection is cleared. Current treatments for many cracks involves the use of

synthetic epoxy and hoof repair materials. Before these materials are placed in

the crack, the crack should be thoroughly cleaned and possibly burred out to

enlarge the area for the glue or plastic to adhere. Some horses should be shod

with toe clips placed on either side of the crack to prevent it from expanding (see figure

2).

Figure 2

|

White Line Disease (Gravel):

Causative Agent: This problem is caused when an opening or defect in

the white line occurs. This can result from an excessively dry foot or when a

puncture wound, rock, or piece of gravel damages the white line. The opening in

the white line allows infection (not the piece of gravel) to migrate up the hoof

wall through the sensitive structures and drain at the coronary band.

Clinical Signs: White line disease is usually first identified when a

draining tract of infection is noticed at the coronary band; however, some

horses can be lame before the draining at the coronary band ever takes place. If the underside of the foot is examined, a spot or area of blacked

tissue can often be seen in the white line. These areas indicate where the

defect in the white line occurred.

Diagnosis: As mentioned earlier, other problems can also cause draining

at the coronary band (quittor, abscesses). The difference between white line

disease and these others is that it involves the white line from the sole to the coronary band.

Probing and examination of the black spots found in the white line often help

identify white line disease as the problem.

Treatment: The treatment for white line disease is essentially the

same as the treatment for abscesses and puncture wounds.

Problems in the Pastern and Fetlock

- Fractures of the Middle Phalanx (P-2):

Introduction and Causative Agents: Fractures of P-2 can be anything from

a chip fracture to a comminuted (multiple pieces) fracture. When they do occur,

they are often the result of strenuous exercise on firm or packed ground. This

usually happens with middle-aged horses that are used for barrel racing,

cutting, roping, and reining. The hind limbs are more often affected than the

front limbs.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Severe lameness is often noted with these

fractures. Occasionally a "pop" is heard just prior to the horse

becoming extremely lame. In most cases, swelling, pain, and crepitus

("grinding") can be noted just above the coronary band when the area is

handled and the pastern manipulated. Radiographs are the best way to diagnose

each of these problems.

Treatment: Chip fractures can be treated with surgical removal or by

just treating the clinical signs in some minor cases. If one large piece of P-2

is fractured, or if the fracture is comminuted (has multiple pieces), it may be

treated with screws, casting, or by arthrodesis of the joint. All animals are

placed on strict rest for multiple weeks. Many of the more serious fracture

victims do not return to riding condition for 9-12 months. If the fracture is

comminuted, a poor return to normal function should be expected.

Fractures of the Proximal Phalanx (P-1):

Introduction and Causative Agents: Fractures of P-1 are most commonly

a fissure type fracture (a crack that does not go completely through the bone)

or a comminuted (multiple pieces) fracture. These fractures occur when twisting

forces are placed on the limb while bearing weight. This can happen when the

horse makes a sharp turn.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Severe lameness is often noted with

comminuted fractures, while the fissure type fractures have various levels of

lameness. In most cases, swelling, pain, and crepitus ("grinding") can

be noted when the area is handled and the fetlock manipulated. Radiographs are

the best way to diagnose the extent and type of damage.

Treatment: The ideal way to treat many of these fractures is by using

bone screws to put the fractured pieces back together (internal fixation). This

surgery is then followed by casting and strict stall rest for many weeks. Many

of the more serious fracture victims do not return to riding condition for 9-12

months, and if the fracture is comminuted, a poor return to normal function

should be expected.

Ringbone:

Introduction and Causative Agent: Ringbone is the abnormal growth of new

bone that forms on the long pastern, short pastern, or coffin bone (proximal,

middle, or distal phalanx). When this bone growth occurs on the long pastern and

the top (proximal) end of the short pastern, it is called high ringbone. When it

occurs on the lower (distal) end of the short pastern and the coffin bone, it is

called low ringbone. Ringbone can be found in horses that make quick stops and

twisting turns at high speeds (performance, polo, etc.). It is also common in

draft type horses that are not worked at speeds, but have a "boxy"

conformation in the pastern.

Ongoing inflammation of the periosteum (periostitis) that covers each bone

causes high and low ringbone. When the periosteum is inflamed, the horse’s

body lays down new bone in the inflamed area. The inflammation of the periosteum

can be caused by pulling and stress on the joint capsule, tendons, and ligaments

that are found in these areas. A fracture to any of the bones in this region can

cause ringbone to form. A wound that involves the periosteum can also cause

ringbone. Often, it is the poor conformation of the horse that causes the excess

stress on the joint capsule, tendon, or ligament.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: These horses are often lame and may have

swelling, heat, and pain associated with the locations of the ringbone. These

areas may be firm and irregular to the touch. Ringbone problems most often occur

in the front limbs. If low ringbone affecting the extensor process of the coffin

bone is the problem, the foot may take on "buttress foot" appearance.

A buttress foot is one where the excess bone causes the top (dorsal) surface of

the foot around and above the coronary band to bulge. The shape of the hoof wall

can also be distorted. To diagnose ringbone, a radiograph must be taken. On the

radiograph, evidence of excess bone production and arthritis can be noted.

Treatment: The treatment for ringbone is based on preventing any

additional movement to the joint(s) in the involved areas. This sometimes occurs

naturally when the bones on either side of a joint fuse and cause ankylosis of

the joint. There are different surgical procedures that can accomplish the same

fusing or athrodesis of the joint. Some horses never return to full function

even with surgery, and attempts to manage this disease without surgery are

usually unsuccessful. The key to successful treatment involves diagnosing this

problem early and implementing appropriate treatment in a timely manner.

Windpuffs and Thorough-pin:

Introduction and Causative Agents: Windpuffs is the common term for

inflammation of the synovial membrane lining the fetlock and the digital flexor

tendon sheath. Tenosynovitis is the term used to describe inflammation of the

synovial membrane (synovitis) lining of the tendon sheath. Windpuffs can sometimes be a

combination of synovitis and tenosynovitis. When these structures become

inflamed, excess joint fluid is produced and the joint capsule/tendon sheath

expands. Injury to the fetlock joint causes the inflammation. These injuries are

often the result of poor conformation (straight fetlocks) or heavy training.

Clinical Signs: The excess fluid causes a soft, fluid-filled bulge to

appear just above the fetlock joint, behind the back of the cannon bone (see

figure 3). This swelling is not hot, and the horse should not be in pain or

lame.

| Figure 3: Mild windpuffs |

|

Treatment: In many cases, resting the horse will help alleviate the

problem. In younger horses, the problem will often leave as the horse grows.

Pressure wraps and topical DMSO can be used if the problems persist.

Thorough-pin is the common term for tenosynovitis in the tarsal sheath that

surrounds the deep digital flexor tendon in the hind limb. This condition can be

identified by noting swelling of the tendon sheath above the fetlock on the back

of the hind limb. Thorough-pin is a mild form of tenosynovitis and should be

treated like a horse with windpuffs. Like windpuffs, the swelling in

thorough-pin is not hot, and the horse should not be painful or lame. Often the

cause of thorough-pin is not known.

Problems in the Cannon Bone Regions (Metacarpus, Metatarsus, and Splint

Bones)

- Fractures:

Introduction and Causative Agents: Fractures of cannon bone and splint

bones can be anything from a fissure fracture to a comminuted (multiple pieces)

fracture. These fractures are most commonly caused by traumatic injury due to

kicks, falls, slipping, and other accidents. In foals this injury can be caused

by the mare stepping on the foal. Splint fractures are usually the result of

interfering or a kick from another animal.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Non-weight bearing lameness is often noted

with fractures of the cannon bone. In most cases, swelling and pain can be found

in the cannon area. Radiographs are the best way to diagnose each of these

problems. See the discussion on "splints" for more details on clinical

signs and diagnosing this problem.

Treatment and Prognosis: For treating many of the uncomplicated fractures

or fissures, a cast is often used. If one large piece is fractured, or if the

fracture is comminuted (has multiple pieces), it may be treated with screws,

pins, and plates. Many times a cast is applied after the surgery to help provide

support to the healing bone. Fractures of the splint bones are usually removed

surgically. All animals are placed on strict rest for multiple weeks. Many of

the younger horses with these types of fractures do fairly well after successful

treatment. If the horse is older, the fracture has broken the skin, or the

fracture is comminuted, the prognosis is poor.

Splints:

Causative Agents and Clinical Signs: "Splints" are basically

fibrous and/or boney proliferation that takes place between the splint bones and

the cannon bone. Each splint bone is attached to the cannon bone by an

interosseous ligament. Anything that causes stretching or tearing of the

ligament and inflammation in these areas can cause splints to occur. A fracture

of the splint bone can also result in a lesion. When inflammation is present,

periostitis of the splint bone occurs and a splint will develop. Splints

appear as firm to hard lesions near or on the splint bone itself (see figure 4).

In the early stages, the horse may be lame and the splint may be painful and

swollen. As the initial inflammation subsides, the lesion may actually decrease

in size, but become more firm. This problem most often occurs in the front

limbs. Most splints are caused by four major things: interfering (trauma), over

nutrition (calcium and phosphorus imbalances), over-working, or poor

conformation (bench knees, or really base narrow and/or toed-out horses).

| Figure 4: Splint |

|

Diagnosis: Many cases can be identified by the clinical signs (location,

swelling, heat, and pain). If a fracture of the splint is involved, the swelling

and pain may be more extensive and severe. In some cases radiographs will need

to be taken to determine if a joint or the cannon bone is involved. If

interfering is suspected, place white chalk on the inside hoof of the opposite

limb. Work the horse and watch for evidence of chalk on the splint area.

Treatment: The treatment will vary depending on the cause; therefore, it

is important to determine the exact cause of the splints. For interfering

problems, using good splint boots will help resolve the problem. The idea behind

splint boots is to prevent the opposite limb from contacting the shin (cannon)

area. These boots contain some type of thickened material for protection. The

key to placing the boots is not necessarily how tight they are, but that they are placed properly to protect the shin

(cannon) bone areas. The horse should also be evaluated (by owner and farrier)

for any trimming or shoeing reasons for the horse to interfere. Most

conformation problems are difficult to correct. If nutrition in a young horse

might be the problem, use the information on page A575 to calculate what is

being fed. If the ration seems too hot, take measures to decrease the amount of

energy (TDN) being fed.

Anti-inflammatory agents (bute,

topical DMSO) and cold water soaks are essential for splints that are painful, tender, and

swollen. Cold water/ice can be applied

20 minutes twice a day for 5-7 days. After the soaks, pressure wrapping the

involved areas can also help. Rest is also essential until the inflammation has

gone down (30-45 days). If the splints are more chronic (have been going on for

some time), the above may not be useful. In these cases the extra bone may have

to be removed by surgery. In general, if the initial inflammation is reduced

early on, the outcome is usually favorable. It is also essential to remove the

cause (nutrition problems, interfering, etc.). Most splints resolve with time

and proper treatment.

Stress Fractures, Bucked Shins, and Shin Splints of the Cannon Bone:

Introduction and Causative Agent: All of these terms are used

to describe injury to the cannon bone that takes place when severe compression

forces are placed on the limb during impact. When bone remodeling cannot keep

up with the repeated stresses, defects in the bone occur. These injuries most

often occur in young animals (2-3 years of age) that are under extensive

training programs.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: In the acute, mild form of the disease,

the horse may be in pain when pressure is placed on the involved area of the

cannon bone. The horse is usually only sightly lame and the condition may even

go unnoticed. If the problem progresses, swelling may be felt on the

front/middle (dorsomedial) surface of the cannon bone. The pain is usually more

severe at this stage. In the early part of this problem, radiographs are often

normal. As the problem progresses, radiographs may show a subperiosteal callus

forming in the injured areas of the cannon bone. These calluses are the way the

bone tries to heal itself by laying down extra bone for added strength.

Occasionally, fractures are observed on a radiograph.

Treatment: For the more mild cases, rest and daily hand walking are

recommended. This should be continued until the cannon bone is no longer painful

to pressure. After this, the horse can be placed on a controlled exercise

program. The length and duration of the controlled exercise program is

determined by how well the cannon remains unpainful. Anti-inflammatory agents

are also of benefit. For the more severe cases, the extent of rest may go as

long as one year. There are some surgical procedures for those cases that do not

respond to rest and anti-inflammatory agents.

Problems in the Knee (Carpus) and Upper Front Limb:

- Fractures:

Introduction and Causative Agents: Most of the fractures in the knee are

associated with the small carpal bones and end of the radius that form the

joint.

Horses that jump, race, and do athletic performances are prone to developing

these types of fractures. When horses perform these types of activities, the

knee is under significant amounts of compressive pressure. These forces result

in chip, slab, and comminuted fractures. Direct injury from a kick or blow can

also cause a fracture.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Swelling, pain, and lameness are common

signs. Physical examination using flexion tests and injections of anesthetic

into the joint can help identify a knee problem. To determine the exact location

of the fracture, radiographs are essential.

Treatment and Prognosis: Small chip fractures that are still adhered to

the larger piece of bone can often be treated with rest and anti-inflammatory

agents. The horse should be confined for 6-12 weeks and then hand-walked for

another 6 weeks. Large chip fractures can be treated with surgical removal.

After surgery, they should be rested for 6-7 months. A slab fracture can be

treated with a screw or surgically removed. These animals should also be rested

for 6-7 months. Surgical treatment for comminuted fractures is often

unsuccessful and is only used for animals that have breeding potential. Many

chip fractures that are treated early and properly, have a good return to normal

function. However, most of the slab and particularly the comminuted fractures

have a poor prognosis.

Fractures in the Upper Front Limbs:

Introduction and Causative Agent: Fractures of the radius, ulna,

humerus, and scapula will be discussed below. Other fractures in the lower limbs

have already been discussed and fractures in the hind limbs will be discussed

latter. In general, fractures that occur in foals have a greater chance of being

treatable. Direct injury or trauma to the area is usually the cause of these

fractures. This injury can come from a kick or accident (collision). The

resulting injury can be anything from a fissure fracture to a comminuted

(multiple pieces) fracture.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Non-weight bearing lameness is often

noted with these fractures. In most cases, swelling, pain, and crepitus

("grinding") can be found when the area is handled and manipulated.

Diagnosing these injuries is not usually difficult and radiographs are the best

way to determine the extent and type of fracture.

Treatment and Prognosis: For some minor fractures of the ulna, strict

stall rest may be all that is needed for the fracture to heal. More complicated

fractures of the radius and ulna are best treated with surgery. During the

surgery, plates and screws are used to hold the fracture in place. Fractures of

the humerus may be treated with strict stall rest, slinging the horse, and

bandages. Foals respond better to this treatment than do adults. Foals with

humerus fractures may also be treated with pins and potentially plates and

screws. Radial nerve paralysis is sometimes a problem with fractures of the

humerus.

Fractures of the scapula can sometimes be treated with rest, and if

necessary, surgical removal of any small, boney fragments. Some scapula

fractures in foals may be treated with plates and screws. If the fracture of the

scapula involves the shoulder joint, there is often no effective treatment.

No matter what type of fracture has occurred, attention should be given to

the opposite limb. In many cases, the opposite limb will be forced to bear most

of the weight. This can result in laminitis, angular limb deformities, and other

problems.

Many of the younger horses with these types of fractures do fairly well after

successful treatment. If the horse is older, the fracture has broken the skin,

or is comminuted, the prognosis is poor.

Problems in the Hock (Tarsus):

- Bog Spavin:

Introduction and Causative Agents: Bog spavin is the common term for

synovitis in the hock or tarsal joint. Synovitis is inflammation of the synovial

membrane covering the joint. When it becomes inflamed, excess joint fluid is

produced and the joint capsule expands. Repeated injury to the hock joint causes

the inflammation. These injuries are often the result of poor conformation

(straight, cow, or sickle-hocked) or heavy training. Improper shoeing,

fractures, and osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) can also cause this problem. Some

studies show that nutritional imbalances and deficiencies (low calcium, vitamin

D & A, and phosphorus) may also play a role in the development of this

disease. This most commonly occurs in animals 6 months to 2 years of age.

Clinical Signs: The excess joint fluid causes soft, fluid filled

bulges to appear on the inside and outside areas of the hock (see figure 5).

Like windpuffs, these swellings are not hot, and the horse should not be in pain

or lame unless the bog spavin is due to an injury or OCD lesion. As pressure is

placed on one of the swellings, the fluid will be pushed to other swellings and

make them larger.

| Figure 5: Bog spavin |

|

Diagnosis: It is important to determine the exact cause for the joint

swelling (OCD, trauma, nutrition, etc.). To do this a radiograph is a must.

Treatment: In many cases, resting the horse will help alleviate the

problem. In younger horses, the problem will often leave as the horse grows. If

the problem is due to OCD, surgical treatment of the lesion is necessary. When

nutritional deficiencies are the cause, supplementation is required. If the

problem is severe or the horse is lame and painful, injections of

corticosteroids and other products may be given in the joint. Some of the

anti-inflammatory and glycosaminoglycan products may also be of benefit. Because

no treatment seems to be 100% effective, bog spavin is sometimes a difficult

problem to completely cure. This is particularly true if the problem is caused

by a conformation defect or trauma.

Bone Spavin or Jack Spavin (Degenerative Joint Disease of the Distal

Tarsal Joints):

Introduction and Causative Agents: Bone spavin is found most often in

horses that are ridden at high speeds, where they are used for jumping, reining,

roping, and cutting. Damage and inflammation occurs in the lower bones and

joints of the hock when compression and rotation stresses are placed on the hock

during these exercises. Like bog spavin, these injuries are often the result of

poor conformation (straight, cow, or sickle hocked). Some studies show that

nutritional imbalances and deficiencies may also play a role in this disease.

Clinical Signs/Diagnosis: These horses

often have a history of being moderately lame after exercise, but improve with

rest. These horses are positive to the spavin or hock flexion test. To perform a

spavin test, the limb should be held in this position, with the cannon bone

parallel to the ground, for 1-2 minutes (see

figure 6). Once the limb is released, watch the horse for signs of lameness as

it is trotted away. Because of the inflammation to the periosteum (periostitis),

extra bone is formed over the front and inside areas of the hock joint. As a

result, a firm, boney bump can often be detected on the inside (medial) portion

of the lower hock (see figure 7). Radiographs are very important in diagnosing

this disease. Multiple views of both hocks are often necessary to help identify

the problem.

|

Video clip of a spavin test being performed. |

|

|

|

If the video

does not play, you must install an MPEG video

player on your computer (e.g. Windows Media Player).

Click here to

download Windows Media Player.

Or

Install Internet Explorer from our CD Manual. |

| Figure 7: Bone spavin |

|

Treatment: In many cases of bone spavin, treatment efforts are not very

effective. Many horses remain lame and never return to full function. There are

various surgical techniques that can be used to help treat bone spavin. The most

common is a procedure called a cunean tenectomy. This procedure removes the

portion of the cunean tendon where it moves over this region of the hock.

Corrective shoeing can also help many of these horses. The intent of the

corrective shoeing should be to cause the foot to break-over quicker. This can

be accomplished by using a rocker or rolled toed shoe.

Curb:

Introduction and Causative Agents: Curb is a condition where the back

(plantar) aspect of the fibular tarsal bone is enlarged. This results from an

enlargement of the plantar ligament due to inflammation and thickening. In some

cases periostitis is involved and there is an extra layer of bone in that

region. The plantar ligament is located in the area just below the point of the

hock. Inflammation of the plantar ligament is often the result of poor

conformation (straight, cow, or sickle hocked) or when the horse injures itself

in the hock region by kicking against trailers or walls.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Signs of heat, swelling, pain, and lameness

are common early on in the condition. As things progress, scar tissue and an

obvious bump may be noticed (see figure 8). Radiographs can help determine the

cause and extent of a suspected case of curb.

| Figure 8: Curb |

|

Treatment: In many cases, resting the horse will help alleviate the

problem. Rest should be accompanied by ice packs, anti-inflammatory agents, and

corticosteroid injections under the skin in the area of the lesion. In cases

that have been going on for sometime, successful treatment may not be

achieved.

Problems in the Stifle and Upper Hind Limb

- Patella Problems:

Introduction: The patella is the horse’s knee cap. It can be

fractured, luxated, or become fixated or "stuck."

Causative Agents: Luxations and fractures are due to trauma caused by

kicks and collisions. Luxations can also be due to congenital abnormalities. The

upward fixation of the patella is caused by genetic traits where the horse has a

"straight hind limb" conformation. Poor muscling and muscle tone can

also be part of the problem. In this situation, the patella becomes fixed or

catches on a ridge (medial trochlear ridge) of the femur. This prevents the limb

from flexing.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: When luxations and fractures are the

problem, the stifle will be swollen and painful. The horse may show varying

degrees of lameness. Radiographs are also helpful in diagnosing these problems.

If the horse has a problem with upward fixation of the patella, the limb may

actually be "locked" in a flexed position where the stifle and hock

cannot flex. If the horse is only "catching" the patella on the ridge,

the horse will have a jerky gait when turned in a circle or walked up or down a

hill.

Treatment: For luxations and fractures, surgical procedures can be

used to help treat the problem. For minor fractures, stall rest and splints may

be all that is needed. Treatment for a fixed patella depends on how severe it is

and if the patella is "locked" or just "catches." For

immediate treatment of a locked patella, the limb can be pulled forward, while

pressure is placed on the patella to force it down and medially. The horse can

also be backed down a hill, while the same pressure is placed on the patella to

force it down and medially. Some recommend startling the horse, causing the

patella to release. This should be done with caution because of the potential

for additional injury. In the more severe cases, surgery can be performed to cut

the medial patellar ligament. This allows the patella to release and prevents

any additional locking of the patella on the medial trochlear ridge of the

femur. Once the surgery is performed, the horse should not be used for at least

6 weeks.

Prognosis: For luxations, the prognosis is guarded to poor. For fractures

of the patella, the prognosis can be favorable if proper and thorough treatment

is implemented. The prognosis for upward fixation of the patella is good as long

as the joint has not suffered any permanent damage.

The following video clip shows a pony with a fixated

patella in the left hind limb. The patella remains fixated throughout

the entire video.

Fractures in the Upper Hind Limbs:

Introduction: Fractures of the tibia, femur, and pelvis will be

discussed below. In general, fractures that occur in foals have a greater

chance of being treatable. Direct injury or trauma to the area is usually the

cause of these fractures. This injury can come from a kick, severe compression

forces, or accident (collision). The resulting injury can be anything from a

fissure fracture to a comminuted (multiple pieces) fracture.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Non-weight bearing lameness is often

noted with these fractures. In most cases, swelling, pain, and crepitus

("grinding") can be found when the area is handled and manipulated.

Diagnosing these injuries is not usually difficult and radiographs are the best

way to determine the extent and type of fracture.

Treatment and Prognosis: In general, most significant fractures in the

tibia or femur of an adult horse are difficult to treat. Many of these horses

should be euthanized. This statement is also true for many fractures of the

femur in a foal. On the other hand, some minor fractures of the tibia can be

treated with only strict stall rest. The more complicated fractures of the tibia

and femur in a foal can sometimes be treated with surgery and/or cast

application. During the surgery, plates, screws, and pins may be used to hold

the fracture in place. There is no surgical treatment for fractures of the

pelvis. A fractured pelvis may be treated with strict stall rest for as long one

year. Slings may also be used for the first 6-8 weeks. Because there is such

variability in the types and treatments of these fractures, a veterinarian must

be involved in each individual case.

Again, no matter what type of fracture has

occurred, attention should be given to the opposite limb. In many cases, the

opposite limb will be forced to bear most of the weight. This can result in

laminitis and other problems.

Some foals with these types of fractures

do fairly well after successful treatment. If the horse is a yearling or adult,

the fracture has broken the skin, or the fracture is comminuted, the prognosis

is poor.

Problems in the Neck Region

- Wobbler Syndrome:

Introduction: The term "wobblers" is often used to describe

any condition of the horse where weakness and coordination problems are

involved. This condition can be caused by deformed vertebrae in the neck

(cervical vertebral malformations), equine protozoal myeloencephalitis

(EPM),

equine herpes, equine infectious anemia, trauma, and others. This discussion

will describe wobbler syndrome caused by deformed vertebrae in the neck. The

other conditions have been discussed elsewhere in this manual.

Causative Agent: Wobbler syndrome is caused by a defect in the

vertebrae of the neck that compresses the spinal cord. The deformed vertebrae

can compress the spinal cord all the time or only when the neck is flexed.

Studies indicate that this condition has some genetic and nutritional influences

that cause the vertebrae to not form properly. Horses that are fed high energy

diets, grow rapidly, and are large at a young age are more at risk.

Clinical Signs: Ataxia (balance problems), gait abnormalities, and

weakness are some of the common signs. Many horses are in pain and reluctant to

move their necks. Some horses recover and remain fairly normal, while others

digress to an unmanageable state.

Diagnosis: A physical exam will help to identify the possible location of

the problem. Radiographs are essential to determine exactly where the problems

are located and the severity of the deformities. These examinations may also

reveal degenerative joint disease (DJD) and osteochondritis dissecans (OCD)

lesions.

Treatment and Prognosis: Some mild cases may respond to anti-inflammatory

agents (steroids, bute) that help to reduce the inflammation in the spinal cord

and surrounding areas. This type of treatment only produces temporary

improvement, with the horse continuing to have problems. In most cases the

surgical treatment is a must. The surgical procedures that are commonly used are

designed to provide increased stability to the neck vertebrae. Most surgical

cases can return to breeding and a few horses may return to normal or near

normal function. Horses that show few clinical signs prior to surgery, have a

better chance of gaining a favorable recovery.

Problems Found in Many Different Joints and Locations

- Angular Limb Deformities:

Introduction: Angular deformities are defects where the limbs are

deviated in an abnormal position. These problems most often occur in young

animals. A section of the limb may be deviated away from the body (lateral

deviation or valgus deformity) or towards the body (medial deviation or varus

deformity). These deformities are most often found in the fetlock and carpus of

the front limbs. When an inward deviation of the limb above the knee and an

outward deviation of the limb below the knee takes place, it is called carpus

valgus or knock-kneed. A bowlegged animal is considered carpus varus.

Causative Agents: Congenital (present at birth) angular limb

deformities can be the result of nutritional imbalances of the mare, improper

positioning of the foal in the uterus, defective endochondral ossification, and

abnormal development of some of the bones associated with the joint. Acquired

angular limb deformities are developed during the first few months of life.

These can be caused by trauma or growth plate injuries, joint instability,

nutritional imbalances (too much or too little energy, phosphorus, and calcium),

defective endochondral ossification, abnormal development of some of the bones

associated with the joint, and abnormal weight bearing on a joint/growth plate

because of poor conformation, improper trimming, and excessive exercise.

To fully understand why these problems occur in growing animals, it is

necessary to have a basic knowledge of how long bones (radius, cannon, etc.) and

the small bones of the carpus (rows of carpal bones) are formed. Each long bone

in the body has a physis or growth plate. This is responsible for the up and

down (longitudinal) growth of each bone. Each long bone and the small cuboidal

bones of the carpus also rely on a process called endochondral ossification for

final bone maturation. Endochondral ossification is where cartilage (in the

epiphysis or ends of the long bones) actually ossifies to form bone. Any

process that injures the way the growth plate and endochondral ossification

function can result in angular limb deformities.

When abnormal amounts of

weight and pressure are placed on a growth plate or area of endochondral

ossification, the growth is stunted. For example, one way to cause a carpus

valgus deformity in a foal is to have an injury or poor conformation that causes

abnormal weight to be placed on the outside regions (lateral aspect) of the bone

(radius) above the knee (carpus) in the front limb. In this case, the outside

portion of the growth plate will NOT grow properly, while the inside (medial

aspect) will continue to grow. This causes the bone (radius) to cup or dish,

forcing the knees together. Nutritional imbalances, injury, and improper weight

bearing can also cause the growth plate to become inflamed (physitis) or even

close prematurely. This can result in abnormal growth and angular limb

deformities.

Clinical Signs: In severe cases, it is obvious that there is a problem

just by looking at the limbs. The horse may be lame and have swollen and painful

joints or growth plates.

Diagnosis: Radiographs are essential in identifying the location and

severity of the problem. A complete history should be taken and include the

following questions: Was the foal born this way? What is the diet? Was the mare

overweight during the pregnancy? Have there been any injuries to the limbs or

limb? A diagnosis can be reached based on the history, physical exam, and

radiographs.

Treatment: Treatment in all cases varies according to the cause of the

deformity. In general, there are three common avenues of treatment:

- Stall rest, corrective trimming, proper nutrition, and time. The

trimming should involve shortening the high side of the hoof wall. In carpus

valgus problems, this means shortening the outside (lateral) portion of the

hoof. Proper nutrition can include alfalfa hay, limited amounts of

concentrates, and access to a high phosphorus mineral supplement. For many of

the minor deformities, this may be all that is needed to correct the problem.

Many young foals will correct a deformity on their own within the first few

weeks of birth.

- Placing the affected limb in a tube or sleeve cast. This is commonly

used for joint instability problems.

- Surgical procedures. A surgical procedure called periosteal stripping is

commonly performed. During this procedure, the outer surface of the bone (periosteum)

is removed to stimulate bone growth. A different surgical procedure (sometimes

done on the same animal) called transphyseal bridging is also used. This is

where screw, wires, or staples are placed across one side of a growth plate to

prevent additional growth. These devices are removed once the deformity has

been corrected.

In general, if the problem is corrected early, most young foals have a

successful outcome.

Flexural Limb Deformities (Contracted Tendons):

Introduction: Flexural limb deformities are situations where the

various joints of the body are held in some degree of flexion. This is most

often the result of a contracted tendon. These problems are identified as

congenital (present at birth) or acquired (occurring after birth).

Causative Agents: Congenital deformities are most often caused

by malposition during the pregnancy, the mare ingesting toxic substances, and/or

inherited genetic defects. Acquired defects are often the result of pain

(epiphysitis, osteochondrosis, injury), genetics, nutritional imbalances

(excessive energy intake), and rapid growth. A combination of two or more of

these problems may also be the cause in some cases.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: In many cases more than one limb is

involved. Most of the time the knee (carpus) or fetlock is involved, and these

joints are often "popped" forward. The joint is held in this flexed

position, and may or may not be forced to a normal position with pressure. The

acquired cases will often result in a "club foot," where the horse

bears its weight on the toe.

Treatment for Congenital Deformities: Some horses will correct the

problem on their own with little or no human intervention. More complicated

cases can be helped/treated in one of three ways:

- By applying PVC splints to help "force" the joint back into

place. This should be done carefully, with plenty of padding and continual

observation. The PVC can be bent to accommodate the proper angles of the limb.

If care is not taken in the proper placement of these splints, sores and

injury can result.

- By applying a cast and potentially corrective shoes. This is reserved

for the more complicated cases and requires special attention by the owner and

veterinarian.

- Through surgical procedures. These surgical procedures are most often

used in the acquired flexural deformities and are not usually successful with

the congenital problems.

Treatment for Acquired Deformities: Some horses will correct the problem

on their own with exercise, proper nutrition, and corrective trimming. More

complicated cases are corrected through surgical procedures. The object behind

these procedures is to release tension placed on a contracted tendon. The common

procedures are flexor tenotomies and inferior check ligament desmotomies.

Arthritis, Osteoarthritis, and Osteochondritis:

Introduction: Arthritis is inflammation of a joint, which can be caused by

injury (trauma) or infection. If the arthritis is severe and untreated, it may

progress into degenerative joint disease (DJD) or osteoarthritis. Arthritis can

involve inflammation of the synovial membrane, joint capsule, cartilage, and

even bone. If both bone and cartilage are inflamed, it is called osteochondritis.

Causative Agents: A single or repeated injury to any joint in the body

can result in arthritis. This injury can be from excessive strain (racing,

working, etc.), or from a physical blow to the joint (kick, fall, etc.) causing

a fracture, sprain, or luxation. The most common causes of infectious arthritis

are bacteria (E-coli, Actinobacillus spp., Salmonella, Streptococcus spp.,

Pseudomonas spp, Corynebacterium equi, etc.) that invade the joint through a

wound or by the blood stream. These bacteria can enter the blood stream by an

umbilical infection, pneumonia, or other type of infection within the body.

Clinical Signs: In most cases, the affected joint will be hot, swollen,

and painful. The horse can be moderately to severely lame. When the problem

joint is flexed, the horse will often pull away, flinch, and act very painful.

Diagnosis: In both infectious and traumatic arthritis, it is important to

compare a normal joint with the problem joint. This can be done by palpating

(feeling) the normal and then the abnormal joint. Radiographs should also be

taken. To help with comparison, these radiographs should be taken of the normal

and abnormal joint in some circumstances. With the proper preparation and

technique, a veterinarian can take a sample of the joint fluid from a swollen

joint. This can be examined for evidence of infection (culture and sensitivity,

cell counts) and inflammation (increased protein, abnormal appearance). In some

cases an arthroscopic examination may need to be performed before a complete

diagnosis can made.

Treatment: For the traumatic causes of arthritis, the extent of the

damage must be identified with radiographs, and potentially, arthroscopy. Any

damaged cartilage, bone, or other joint structure must be removed or repaired.

The horse should be rested and some mild forms of flexion of the joint can be

used. Excessive hand walking should be avoided. Cold water hydrotherapy should

begin within 48 hours of the injury. This can involve cold water from a hose,

bathed over the affected joint for 15-20 minutes twice a day. After the initial

inflammation has gone down, the benefits of the cold water soaks are reduced.

Anti-inflammatory agents can also be used to help reduce the pain and

inflammation. Products like phenylbutazone (bute) and DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide)

are anti-inflammatory agents that can be administered by the owner. In some

cases injections of corticosteroids and Legend (hyaluronan) can be given

directly in the joint. Other joint protecting/healing products can also be

administered. These products include injectable polysulfated glycosaminoglycans

(Adequan) and oral glycosaminoglycans (Cosequin, Glyco-flex, and Power-Flex).

MSM is a naturally occurring sulfur compound that is a found in all living

things. It too can have a positive effect on the joints by reducing

inflammation. For additional information on many of these products, refer to

Section H of this manual.

In addition to many of the above

suggestions, arthritis that is due to an infection should be treated with

antibiotics.

Capped Hock, Capped Elbow (shoe-boil), Bicipital Bursitis

(shoulder), and Carpal Hygromas:

Introduction: These conditions are usually caused by injury to a bursa

resulting in bursitis. A bursa is a "cushion" between moving parts or

between various points of increased pressure (like between a bone and tendon).

When a bursa becomes irritated and inflamed it is called bursitis. Bursitis in

the hock is usually caused by the horse kicking something and hitting the point

of the hock. Bursitis in the elbow is often the result of a shoe coming up and

impacting the elbow. Hygromas in the knee (see figure 9) are also caused by

direct injury. In these cases, however, a bursa is not usually present before

the injury, but forms after repeated trauma.

| Figure 9: Carpal hygroma |

|

Clinical Signs: Some pain, heat, and swelling are the most common signs.

If the injury is significant, the swelling can be quite large and there can be

some soft tissue thickening.

Treatment: In most cases, the bursitis can be treated with ice packs,

anti-inflammatory agents, and rest. It is also important to prevent additional

injury to the bursa (remove the shoe on that foot, etc.). For more severe cases,

injections into the problem area and surgery may be required.

Epiphysitis:

Introduction: "Epiphysitis" is a problem that is commonly

found in young, growing animals (ages 4-8 months) and young horses beginning

training. The term "Epiphysitis" is somewhat misleading because the

problem actually involves the growth plate and not the end (epiphysis) of a long

bone.

Causative Agents: Fast growing, young animals that are fed high grain

rations seem to have the most problems. Genetics may also play a role in the

fact that faster growing foals experience epiphysitis. Abnormal weight bearing

and trauma/injury to the growth plate are sometimes associated with this

disease. Studies indicate that a combination of these influences is often the

cause. With the above being the known causes for epiphysitis, how they actually

cause the disease is less understood.

Clinical Signs: The most obvious sign is a "flaring" or

enlargement of the ends of the long bones. This commonly is seen above the knees

on the end of the radius. As the problem progresses, the end of the bone begins

to take on a "hour glass" shape. Depending on the severity of the

disease, the horse may or may not be lame. The horse may act painful when the

involved area is palpated or handled.

Diagnosis: Physical exam and radiographic images are often sufficient

to diagnose this problem.

Treatment and Prevention: The most important step in treating and

preventing this disease is to evaluate and adjust the horse’s ration. Any

nutritional imbalances should be corrected. Use the information found on page

A575 and the details contained below on nutrition to help calculate a proper

diet. Mineral analysis may need to be performed to determine any deficiencies or

excesses of the trace minerals. If the horse is over weight, restrict the amount

of energy being fed. Some horses may recover with rest and the proper use of

anti-inflammatory agents (bute). If anti-inflammatory agents are used, the foal will use the limb

more as the pain and inflammation is reduced.

This potentially can result in additional injury and epiphysitis. If radiographs show that

there are other problems (OCD lesions, angular limb deformities), these will

need to be corrected to help alleviate the epiphysitis. Many horses seem to

recover with time and rest; however, they never return to full performance

ability.

Luxations:

Introduction and Causative Agents: A luxation is a dislocation of a

joint and can occur in the fetlock, knee (carpus), shoulder, hock (tarsus),

stifle, and hip. These injuries most often occur when the limb is forced in an

abnormal direction. This can happen when the horse steps in a hole, falls,

slips, jumps, or twists the limb while in a flexed or extended position.

Clinical Signs: The limb that is involved often has a angular

deformity, where the portion of the limb distal to luxated joint is deviated

outward or inward. The joint itself maybe swollen, painful, and unstable. There

will also be varying degrees of lameness.

Diagnosis: Diagnosing the location of these injuries is not usually

difficult. Radiographs are the best way to confirm a diagnosis and determine if

any fractures are involved.

Treatment: Treatment for most luxations requires that the horse be

anesthetized and the dislocation be reduced or put back into place. This should

take place as soon as possible after the injury. Depending on the location of

the luxation, casts may also be applied. Any chip or other type of fracture

should be treated appropriately.

Prognosis: Many of the minor luxations where no fractures are involved

will often have a good recovery and return to performance. Luxations of the hip

joint, however, may never return to normal even after the head of the femur is

put back into place. If fractures, infection, or degenerative joint disease (DJD)

occur, the prognosis is poor.

Osteochondrosis, Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD), and Subchondral Bone

Cysts:

Introduction: Osteochondrosis is a defect in the normal development of

cartilage. This defect occurs sometime in the process of endochondral

ossification. Endochondral ossification is where cartilage (in the epiphysis or

ends of the long bones) actually ossifies to form bone. If endochondral

ossification does not progress normally, defects called osteochondritis

dissecans (OCD) or subchondral bone cysts can result. OCD lesions are places

where fragments or flaps of cartilage associated with the joint are separated

from the rest of the cartilage. Bone cysts are areas in the end of the bone

where endochondral ossification does not progress normally. This leaves small

areas of cartilage deep within the end of the bone. These areas necrose or die

and leave a defect in the end of the bone.

Causative Agents: The following are thought to cause these defects in

a growing animal:

- Genetic influences.

- Nutritional imbalances (too much energy and mineral imbalances).

- Very rapid growth.

- Trauma and injuries.

It is sometimes difficult to identify just one specific cause for these

defects, so the problem may actually be a combination of the above.

Clinical Signs: OCD lesions are found in the following joints: the

stifle, hock (tarsus), shoulder, fetlock, knee (carpus), elbow, and hip. Bone

cysts are found in the following areas: the stifle, knee (carpus), hock

(tarsus), fetlock, pastern, coffin, shoulder, and elbow. In the case of OCD

lesions, the affected joint may be swollen, painful, and hot to the touch. The

horse is often lame. Cystic lesions are sometimes more difficult to diagnose.

These horses may or may not have swelling and lameness. If these signs do

appear, it is often after work, training, or exercise.

Diagnosis: Radiographs are essential in diagnosing these problems. In

many cases it is helpful to radiograph the opposite joint to use as a

comparison. Nuclear scintigraphy can also be used to help identify the problem

area.

Treatment: For some of the minor OCD and bone cyst problems, the horse

can be treated conservatively with rest and proper nutrition. Not all cases and

not all lesions will resolve by this approach. Some cases require that surgery (arthroscopic

or arthrotomy) be performed. For OCD lesions, the flap is removed and the area

of the defect cleaned.

Tedonitis ("bowed tendons"), Tenosynovitis, and Desmitis:

Introduction: Tendonitis is inflammation of a tendon, while desmitis is

inflammation of a ligament. The most common ligament problem is suspensory

ligament desmitis. Tenosynovitis is inflammation of the synovial lining of a

tendon sheath. In many instances, the inflammation includes not only the tendon

sheath but also the tendon itself.

Causative Agents and Clinical Signs: In most cases, these problems are

caused by severe straining and over-stretching of the tendon or ligament. This

can occur when excessive loads are placed on the limbs due to sudden turns,

jumping, stopping, or slipping. Things such as improper shoeing, poor

conformation, and traumatic injuries can also cause a problem to develop. When

injury occurs to the tendon, the tendon fibers can be damaged and the blood

supply can be compromised. Severe injury can result in complete rupture of the

tendon.

Clinical Signs: After the initial injury, the involved area is swollen,

painful, and hot to the touch. The horse is often lame and very painful when the

limb is flexed. These injuries can occur in the flexor tendons located behind

the cannon bone ("bowed tendon") in the area just below the knee or hock and

above the fetlock (see figure 10). In some cases it is an injury to the anular

ligament that causes the problem. The anular ligament wraps itself around the

fetlock area (kind of like shrink wrap) and helps to keep all the tendons and

joint structures encapsulated. If the anular ligament becomes inflamed, it may

begin to scar and shrink. The superficial flexor tendon runs just beneath this

anular ligament. If the anular ligament scars and constricts, the flexor tendon

is "pinched." This can be the cause of the swelling above a fetlock

joint. If these problems continue for prolonged periods of time, the tendon can

begin to scar and adhere to surrounding tissues. This will cause a loss of

function and flexibility of the tendon/ligament. In some cases the navicular and

sesamoid bones may be involved. If the sesamoids are inflamed, it is called

sesamoiditis.

| Figure 10: Bowed tendon |

|

Diagnosis: Many cases are identified based on physical exam and

clinical signs. The severity of the problem can often be determined through the

use of ultrasound and radiography.

Treatment: The key to healing acute tendon/ligament problems is to reduce

the inflammation and keep any additional trauma and swelling from occurring.

Treatments to reduce the inflammation include cold water soaks or ice packs for

20 minutes twice a day for the first 2-3 days and anti-inflammatory agents (bute).

Topical DMSO can also be beneficial in reducing the swelling. Pressure wraps and

even casting can be used in more severe cases to prevent additional stretching

and injury to any of the tendons and ligaments. To prevent additional injury,

strict stall rest (for the first two weeks), followed by mild manipulations of

the injured area, should be used. To help build the tendon, regularly pick up the

foot/leg and move it gently through a series of flexing motions.

Excessive flexion, particularly where the horse shows pain, will cause continued

damage and should be avoided.

After the rest and mild manipulations, carefully choose what activities the

horse is asked to perform. These should be low impact and preferably without a

rider. Some minor tendon stretching will occur with normal use. After

these occasions, reduce the chance for inflammation and swelling by using cold

water soaks and anti-inflammatory agents as needed. If continued irritation

occurs, scaring and permanent injury will result.

For the more chronic tendon/ligament injuries, where scarring and boney damage

may be involved, surgical intervention is often required. There are many

different procedures that can be used. An equine surgeon will need to evaluate

each situation before a recommendation can be given. The usual treatment for

bowed tendons caused by anular ligament problems is a surgical procedure where

the anular ligament is cut. This allows the flexor tendons to move more freely.

Nutrition and Supplements:

Proper nutrition plays an essential role in the development of healthy bones,