F610

Orthopedic Problems

problems found in the front limb |

problems found in the hind limb |

problems found in the spine | problems found in the skull

| arthritis | degenerative joint disease

| anti-inflammatory drugs |

infectious arthritis |

immune-based arthritis |

growing bone diseases |

neoplasia | fractures |

classification of fractures |

managing fractured bones |

infections | osteomyelitis

| septic arthritis

Introduction: Orthopedics is the branch of medicine and surgery that

focuses on the health of the bones and associated tissues. There are many types

of orthopedic problems that affect cats. Many of these incidents are minor

problems that can resolve on their own with rest and time. Minor sprains,

twists, or muscle bruises account for a large percentage of these common

problems. Persistent lameness, any lameness associated with trauma, and severe

lameness problems should always receive the attention of a veterinarian.

Recovery from an orthopedic problem may take weeks to months.

Locating the problem area and potential cause: Limping or lameness is one

of the more common problems encountered by cat owners. Often, the challenge

comes when trying to determine the location and then the cause for the lameness.

At first, it is important to consider the following questions. These are also

questions that a local veterinarian may ask when evaluating the animal:

- What is the activity level of the cat?

- Have there been any prior surgeries or medical problems?

- What is the animalís age, sex, breed, size, diet, and life-style? (For

example, an outdoor cat that frequently gets into cat fights is much more

likely to sustain a bite wound that becomes infected and leads to lameness

than a cat which is kept strictly indoors.)

- Is the cat currently on any medications?

- Has the condition come on suddenly or slowly?

- Does the problem seem to be associated with an injury?

- Does the problem get worse after exercise?

A thorough physical and orthopedic examination should then be performed. The

goal of an examination is to identify the location of the lameness. The

following are some basic steps that are often used when performing an orthopedic

exam:

- The cat should be observed while standing. Signs of muscle shrinking

(atrophy), confirmation abnormalities, swelling, and pain can often be found.

- Next, the patient is observed from the front, side, and rear while

walking and possibly jumping up onto a chair or table. When the lame limb

contacts the ground, the stride of the affected limb is usually shortened as

compared to the opposite, normal limb. When the sound limb hits the ground,

the animal will often spend more time with that limb in contact with the

ground during the walking motion. Other problems that are often noticed

include ataxia (lack of coordination), paralysis, paresis, and short, choppy

gaits. If more than one limb seems to have a problem, a more central condition

may be at fault. It is important to remember that a perfectly normal gait

requires the use of almost the entire nervous system and many of the muscles

and bones of the body. Injury, damage, or tumors that affect the nervous

system, muscles, or bones can cause problems in one, two, or all four limbs.

- Once the problem limb(s) is identified, a thorough examination of the

limb(s) is necessary to further localize the problem. The examination must be

systematic, starting at one end of the limb and proceeding up or down, feeling

every bone and every joint in the limb. Each area of the limb, including

muscles, bones and tendons, is felt (palpated) as gently as possible until the

painful area is identified. All this should be done while the animal is fully

awake without any sedation. Sedation may mask the animalís response to the

testing. Each joint is moved through the entire range of motion by flexing,

extending, and rotating. Each joint should also be felt for evidence of

swelling, pain, heat, lack of motion, instability, crepitus (popping), and

laxity.

Abnormal laxity (slackness) may indicate

ligamentous injury or damage to the joint capsule. Some fractures are often

very obvious, while others may only be identified by excessive movement of the

area, pain, swelling, and lack of use of the limb. A hot, swollen joint often

is the result of an infection causing inflammation. If the injury has caused

the animal to avoid using the limb(s) for a period of time, the muscles may

shrink (atrophy). Injury to muscles is often identified by tenderness,

swelling, pain, and heat.

- After a specific area of injury has been identified, radiographs

(x-rays) are often used to help determine the extent of the damage and

determine the appropriate treatment.

Note: Basic bone and muscle anatomy of the cat can be found on page

A34

of this manual. Pictures of actual radiographs showing different orthopedic

problems can be found throughout the following information. The cost involved in

treating an orthopedic problem may be substantial. However, the outcome is often

good to excellent with proper treatment and patience.

Many of the most common orthopedic problems in cats are included in the

following information. Each disease or problem is categorized in this

information based on where it is located on the body. The front limb will be

covered first, followed by the hind limb. Diseases that affect more than one

area of the skeleton will then be covered separately.

Problems Found in the Front Limb:

Major orthopedic problems that commonly affect the front limb include

fractures, ligament and tendon injuries, growing bone diseases, dislocations,

infections, and cancers.

- Shoulder: The shoulder joint is the connection between the

scapula (shoulder blade) and the humerus (upper leg). Dislocations and

fractures in this area do occur but are unusual in cats because the shoulder

is well-protected by surrounding muscles and other tissues. Arthritis can also occur in the shoulder joint.

- Shoulder joint dislocation can occur as a result of trauma in

cats. X-rays are usually needed to tell the difference between a shoulder

dislocation and a fracture. Treatment always requires professional help.

Sometimes the dislocation may be successfully treated by moving the bones

back into place and having the cat wear a special bandage for

2 weeks. Often, however, surgery is a necessary part of the treatment.

Upper leg (humerus): The humerus is the long bone extending from

the shoulder to the elbow. Fractures of the humerus are uncommon in cats. The

radial nerve is one of the major nerves in the front limb and travels directly

across the surface of the humerus. This nerve can be damaged when the humerus

is fractured. Fractures of the humerus are easily diagnosed with x-rays and

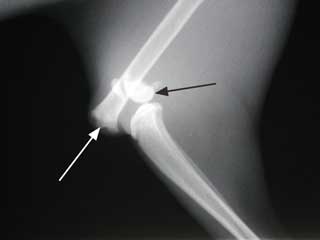

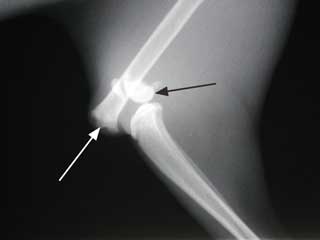

always require surgery to repair (see figure #1).

|

|

|

| Figure 1: Fractured Humerus -

This is a fracture in the lower third of the humerus. The white arrow

indicates the upper portion of the humerus that connects with the

shoulder. This type of fracture would need to be repaired surgically. |

|

Elbow: The elbow joint is a "hinge" joint connecting the humerus

of the upper front limb to the radius and ulna of the lower front limb. The

elbow is relatively unprotected and can be easily damaged and fractured.

Dislocations of the elbow joint can also occur but seem to be less common than

fractures. Arthritis (see below) of the elbow joint can occur,

especially following trauma or injury to the joint.

- Elbow joint dislocation is uncommon but can occur as a result

of severe trauma. The joint is quite stable, and severe trauma is more

likely to result in a fractured bone than in a dislocation of the elbow.

X-rays are needed to tell the difference between fractures and dislocations

of this joint; occasionally, both a fracture and dislocated elbow will be

seen together following a severe blow to a front leg.

Treatment of dislocations requires setting the bones in their proper

positions while the cat is under anesthesia. If the procedure can be done

within a few hours after the trauma, the setting of the bones can often be

performed without surgery. The more time that has passed since the

dislocation occurred, the more difficult it becomes to place the bones back

in their normal positions. Surgery is necessary to set the bones if they

cannot be replaced in their normal positions with anesthesia alone.

Placement of a splint or bandage after setting the bones in place may be

helpful to achieve rapid healing. Arthritis is common later in life in any

joint that has been dislocated.

Lower leg (radius/ulna): The radius and ulna are paired bones

that connect the elbow to the carpus or wrist joint. The radius is the major

weight-bearing bone of the two. Fractures of the radius and/or ulna are fairly

common in cats (see figure #2). When fractures of the lower front limb occur,

both bones are usually broken together. However, it is not uncommon to have a

fractured radius and an intact ulna following trauma to a front limb. X-rays

are usually not needed to know whether a fracture of the lower front limb is

present but are important to determine the nature of the fracture. Many fractures require surgery, while others can be properly treated with

a cast or splint to stabilize the fractured bone(s).

|

|

|

| Figure 2: A fractured radius

caused by a bullet (white arrow). |

|

Carpus (wrist): The carpus is a very complex structure. There are

seven small bones in two rows that connect the lower front limb to the paw and

make up the carpal joints. There is a separate joint connecting each row of

bones, making a total of three joints in the carpus. Injuries to the carpal

joints and bones are not uncommon in cats. Most of these are soft tissue

injuries, involving the ligaments and joint capsule only. X-rays are always

needed following injury to this area to examine the small bones of the carpus

and to determine if any fractures exist. Fractures can occur in any of the

bones of the carpus, although they are infrequent. Dislocations of the carpus

can occur along any of the joints. If there is severe damage to ligaments and

other structures that support the carpus, fusion of the joint (a surgical

procedure called arthrodesis) may be necessary.

- Dislocation of the carpus can occur at any of the three joints

as a result of traumatic injury to the front limb. Damage to the ligaments

and other tissues that support the carpus is usually difficult to repair and

does not heal very well. Special x-ray pictures can help diagnose a

dislocation at one or more of the three joints in the carpus. A dislocation

of any or all of these is generally termed "hyperextension." When

weight-bearing, a hyperextended carpus allows the paw to drop closer to the

ground than normal. The condition is usually quite painful. Minor cases of

hyperextension of the carpus may be successfully treated with a splint or

bandage and strict rest. However, most hyperextension situations require

more aggressive treatment. Fusion of the joint, a surgical procedure known

as "arthrodesis," is necessary in many cases to restore function.

Paw: The feline front paw is made up of five digits (toes), four

of which are weight-bearing. The dewclaw, which corresponds to the human

thumb, sits high up on the inside surface of the front paw and does not bear

weight. There are five bones called metacarpals that extend from the carpus to

each of the five digits. Three bones make up each of the four weight-bearing

digits. These bones are called the first, second, and third phalanges. The

dewclaw has only two phalanges. The nail bed is a delicate tissue arising from

the upper surface of the last phalanx of each digit, and from this tissue each

nail grows. A thick, rubbery pad grows on the underside of each paw, and a

smaller pad grows on the underside of each of the digits. Lameness that

results from pain in the paw is common. Infections of the skin between the

digits and around the pads, abrasions of the pads themselves, and a variety of

cuts and scrapes all may result in pain and lameness. Fractures of the

metacarpals and the digits are also quite common. Finally, cancers of the paw

are rare, but can occur in the nail beds of cats. These nail bed tumors have

usually spread to the nail beds from some other location. Life-threatening

lung and skin cancers have been reported to spread to multiple nail beds in

some cats.

Problems Found in the Hind Limb:

Major orthopedic problem categories that commonly affect the hind limb

include fractures, ligament and tendon injuries, growing bone diseases,

dislocations, infections, and cancers.

- Pelvis: The pelvis is a bony structure responsible for

transferring the weight of the hind end to both hind legs. The pelvis is

divided into different areas. Weight is first transferred from the lower spine

to bones on the right and left sides. These bones are called the ilia

(singular = ilium). The ilia transfer weight to the hip joints. Connecting the

right and left sides of the pelvis are two other bone sets known as the pubis

and the ischium. The ilia, pubis, and ischium together make up the pelvis, a

box-like structure. The acetabulum is the socket-like portion of the ilium

that connects to the femur.

By far, the most common problem encountered involving the pelvis is trauma

and injury. Some estimations report that nearly 25% of all fractures involve

the pelvis. Other problems that may involve the pelvis include dislocations,

infections of the bone or surrounding tissues, and cancers.

- Pelvic fractures are extremely common with trauma of nearly any

type. Because of the rigid box-like shape of the pelvis, fractures are

always multiple and usually occur in sets of three (see figure #3). Pelvic

fractures range from minor to extremely devastating. Because the right and

left ilia are the main weight-supporting portions of the pelvis, fractures

of these bones are usually very serious. Fractures of the socket-like

acetabulum that houses the ball of the hip joint are also extremely serious

and usually result in arthritis of the hip later in life, regardless of how

well they heal. Fractures of the pubic bone are often minor and are allowed

to heal without intervention. Fractures of the ischium vary in severity but

are quite often allowed to heal on their own because they usually do not

affect the animalís ability to bear weight.

Diagnosis of pelvic fractures is made with x-rays. Treatment depends

completely on the situation. Many minor to moderate pelvic fractures can

heal very well with strict cage rest and anti-inflammatory pain killers

alone. More serious types of fractures, such as those that affect the hip

joint or cause changes in the natural shape of the pelvis, should be

treated with surgery. Surgery for pelvic fracture repair is extremely

difficult and is always expensive. Anti-inflammatory pain killers and

laxatives to help reduce pain associated with the passage of bowel

movements are important aspects of the treatment plan for many pelvic

fracture victims.

|

|

|

| Figure 3: Fractured Pelvis -

Notice how the femurs and obturator foramina (white arrows) do not

line up. When the pelvis is fractured, it usually breaks in at least

three places. |

|

- Dislocations of the pelvis can occur with trauma. The only

place in the pelvis where a dislocation may occur is at the attachment of

the ilium to the spine. This is known as the "sacro-iliac joint." A strong

ligament that attaches the ilium to the spine may be torn with severe

trauma.

Like pelvic fractures, pelvic dislocations are diagnosed with x-rays and

treated according to severity and situation. Surgery is often the preferred

type of treatment for pelvic dislocations.

Hip: The hip joint consists of the "ball-and-socket" structure

connecting the pelvis to the hind limb. The femur is the first long bone in

the hind leg that connects the pelvis to the knee or stifle joint. The femur

is the longest bone in the body. As previously indicated, the medical term for

the socket is the acetabulum. The medical term for the ball is merely the

"head" of the femur. A variety of conditions can affect the hip joint.

Fractures and dislocations are common.

- Dislocation of the hip joint is a common result of injury to

the hind end in cats. Blunt force trauma causes the ball to pop out of the

socket, tearing the ligaments and capsule that help keep the joint in place.

Diagnosis of this condition can often be made through examination by a

veterinarian. Confirmation of the dislocation is needed with an x-ray (see

figure #4). The x-ray provides important information for proper treatment

because it will also show the veterinarian what type of dislocation has

occurred. Treatment consists of getting the hip joint back together and

keeping it there. This can be more challenging than it sounds. If action is

taken quickly, the head of the femur may be put back into place by working

the ball back into the socket. This is performed by a veterinarian while the

cat is under anesthesia. Because more inflammation in the injured area

actually "locks" the bones in their abnormal positions, this procedure

becomes increasingly more difficult with the passage of time. If the

dislocation cannot be repaired in this manner, surgery becomes necessary. A

variety of methods are available, depending on the situation.

|

|

|

| Figure 4: Dislocated Hip- The

white arrow identifies the head of the femur that is dislocated out of

the hip socket (acetabulum). Compare this side to the opposite hip

that is not dislocated. |

|

A special bandage called an Ehmer sling is usually placed on the leg

regardless of the type of treatment used. This sling helps to keep the hip

in place while preventing the cat from putting any weight on the leg for up

to 2 weeks.

- Hip dysplasia is far less a problem in cats than it is in dogs,

but is reported in the Siamese breed. It appears to be passed in families

and can result in crippling lameness. Animals with hip dysplasia are born

with normal hip joints, but changes occur during development and aging.

Gradual loosening of the joint with swelling, pain, and damage to joint

tissues occurs.

Diagnosis of the condition must be

made with x-rays and can be treated medically with anti-inflammatory

medications. Surgical treatment is the most effective and rewarding

treatment available. Total hip replacement can be done in cats as it is in

dogs; however, because the condition is seen in cats on a less frequent

basis, the surgery is not routinely performed. A less expensive alternative

to the total hip replacement surgery is called the femoral head and neck

osteotomy (FHO), in which the head and neck of the femur ("ball" of the

ball-and-socket) is completely removed and the upper portion of the femur

allowed to form another "socket" joint with scar tissues (see figure #5).

The surgery is remarkably effective with lightweight animals, and cats tend

to do extremely well following this procedure.

|

|

|

| Figure 5: Femoral head and neck

osteotomy (FHO) - The white arrow shows the location where the head

and neck of the femur used to be located. An FHO surgery has been

performed. |

|

Upper leg (femur): The femur is the long bone extending from the

hip to the knee (stifle). Fractures of the femur are common. Fractures of the

femur are easily diagnosed with x-rays and always require surgery to repair

(see figures #6-7). Repair is often very difficult and can be very expensive.

There are many different ways of repairing a fractured femur, so an orthopedic

specialist should be consulted.

|

|

|

| Figure 6: Fractured Femur -

This is a fracture of the femur just above the bottom or distal end of

the bone. The femur is indicated by the white arrow and the black

arrow identifies the distal end of the femur or the condyles. To

adequately fix this type of fracture, orthopedic surgery is required. |

|

|

|

|

| Figure 7: The black arrow

identifies a bone pin placed to repair the fracture shown in figure #6

above. |

|

Stifle (knee): The stifle joint is another hinge joint like the

elbow but vastly different in many ways. The lower portion of the femur ends

at the stifle joint. On the front side of the lower end of the femur sits the

patella (knee-cap), a small bone that moves up and down as the stifle bends.

Small cushions of cartilage sit in between the lower end of the femur and the

upper end of the tibia. These cushions of cartilage are called menisci (the

lateral meniscus on the outside and the medial meniscus on the inside). Two

ligaments run down the sides of the stifle joint, and two ligaments criss-cross

inside the stifle joint. All these parts are important in the function of the

stifle joint, and all can be injured and lead to pain and lameness.

Injury to the stifle joint is uncommon in cats. When injuries do occur to

this joint, they may involve fractures, ligament injuries, or dislocation.

Probably the most common injury sustained to the stifle joint is the tearing

of one of the inner criss-cross ligaments. The ligament commonly injured is

called the cranial cruciate ligament and is identical to the anterior cruciate

ligament in the human knee joint. Improper movement of the patella or knee-cap

(called patellar luxation) may also occur. Arthritis of the stifle is seen

frequently in older patients, usually as a result of some previous injury or

problem in the joint. Bone cancers, while rare in cats, may affect the stifle

joint area.

- Cranial cruciate ligament injuries occur uncommonly in cats.

When the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) tears, this allows the tibia to

slide forward away from the femur too much when the animal bears weight on

the leg. This excessive movement stretches the other tissues in the stifle

area, resulting in pain. The sliding movement also damages the cartilage

cushions (menisci) that sit between the two bones. Most cats with a torn CCL

are very reluctant to bear any weight on the leg. The lameness can occur

suddenly, although many cats will have been exhibiting an on-off mild

lameness for weeks to months before. Tearing can happen in an otherwise very

healthy stifle joint with a sudden and severe blunt force to the area. More

commonly, however, the ligament will gradually weaken and deteriorate as the

animal ages. Aged, weak ligaments will often tear easily with minor force,

such as slipping or jumping. In many of these cases, an owner will not know

of any trauma received by the pet. It is important to be aware that these

ligaments age and can become weak in both stifle joints over time, and when

the CCL tears on one side, there is a chance that the other will also tear

in time. This likelihood is probably made even greater with the extra weight

borne by the "good" leg when one ligament tears. Overweight cats may be more

likely to suffer CCL tears for the same reason.

Diagnosis of CCL tears is made during

a detailed exam by a veterinarian. The forward movement of the tibia is

detected and helps determine the diagnosis. Some cats may need to be sedated

for a thorough examination if they are too tense or in too much pain. X-rays

can also be helpful in showing inflammation in the stifle joint but cannot

show the actual torn ligament. Torn cranial cruciate ligaments should always

be repaired with surgery. If not repaired surgically, the joint does

stabilize itself the best it can with thickening of tissues. The cat will

improve gradually up to a limited point after many months of lameness.

However, arthritis will always result and is often severe. Thus, if left

alone and not repaired with surgery, the cat will usually appear to improve

for awhile but will end up getting permanently worse in the end. Once the

arthritis sets in, it is irreversible. Prognosis with surgery is usually

good.

- Patellar luxation (dislocation of the knee-cap) is another

uncommon condition of the stifle joint of cats. This condition is seen most

commonly in the Devon Rex and domestic shorthair breeds. The patella usually

dislocates towards the inside of the leg (medially) and is generally

apparent by the time the animal is 4-6 months old. Both stifle joints are

usually affected.

Trauma to the stifle can also cause dislocation of the patella in an

otherwise healthy cat. Patellar instability is graded based on its severity.

Grade 1 is the most mild form, while Grade 4 is the most severe. The more

mild cases will often gradually progress to become severe later on. Some

cats will adapt to the patella popping in and out of place as they walk.

Some cats may hide this problem so well that the owner may not notice any

lameness until the problem is very severe. Arthritis of the stifle is

usually a consequence of patellar dislocation.

Diagnosis of this problem is made primarily by physical examination. A

veterinarian can detect the abnormal movement of the patella and determine

the severity of the problem. X-rays are helpful with the diagnosis,

especially in showing if any arthritis is present.

Treatment depends on the situation. Mild cases with no lameness present

are monitored for worsening of the condition. Severe cases require surgery.

There is a large gray zone in the middle of these two extremes. Treatment

for cases falling in this gray zone, with only occasional lameness and/or

moderate instability, must be judged individually by the owner and the

veterinarian. Surgery can be extremely helpful for one particular individual

but may not work at all in another.

- Stifle dislocation is a very serious problem where numerous

ligaments and other tissues have been severely damaged. It requires a great

deal of force to cause dislocation of the stifle joint. Dislocation of the

stifle joint usually includes tearing and severe damage to both cruciate

ligaments and at least one of the menisci. Diagnosis of this problem is made

by careful examination by a veterinarian while the animal is under

anesthesia. X-rays are very helpful as well, showing damage to parts of the

joint that cannot be examined from the outside. Treatment is best

accomplished by carefully reconstructing the joint. Such a surgery may be

lengthy and very expensive. If reconstructive surgery is successful and

proper care is taken afterwards for healing, the outcome is often

surprisingly good. Mild arthritis and/or stiffness of the joint may result.

Lower leg (tibia/fibula): The tibia and fibula are paired bones

that connect the stifle to the tarsus or ankle joint. The tibia is the major

weight-bearing bone of the two. Fractures of the tibia and/or fibula are

extremely common in cats. When fractures of the lower hind limb occur, both

bones are usually broken together (see figure #8). However, it is not uncommon

to have a fractured tibia and an intact fibula (or vice versa) following a

hind limb trauma.

X-rays are usually not needed to know

whether a fracture of the lower hind limb is present but are important to

determine the nature of the fracture (see below). Treatment of certain

cases requires surgery, while some fractures may be properly treated with a

cast or splint to stabilize the fractured bone(s).

|

|

|

| Figure 8: Fractured Tibia and

Fibula - This is a comminuted fracture of the tibia and fibula. |

|

Tarsus (ankle): The tarsus or hock joint is a very complex

structure. There are seven small bones in two rows that connect the lower hind

limb to the paw and make up the tarsal joints. There is a separate joint

connecting each row of bones. The calcaneus (heel bone) is the largest of

these bones and projects back, toward the catís tail. The Achilles tendon

(common calcaneal tendon) attaches to this bone and travels up to the muscles

on the back of the catís lower limb. The Achilles tendon is rather exposed and

can be injured easily. Injuries to the hock joints and bones are common in

cats. Most of these are soft tissue injuries, involving the ligaments and

joint capsule only. X-rays are always needed following injury to this area to

help evaluate the small bones of the hock and to determine if any fractures

exist. Fractures can also occur in any of the bones of the tarsus. Such

fractures are uncommon. Dislocations of the tarsus can occur along any of the

joints. If there is severe damage to ligaments and other structures that

support the tarsus, fusion of the joint (a surgical procedure called

arthrodesis) may be necessary.

- Dislocation of the tarsus can occur at any of the joints as

a result of traumatic injury to the hind limb. Injuries to ligaments in the

joint and sometimes fractures of the small bones are associated with hock

dislocation. Diagnosis is made through careful examination by a veterinarian

and x-rays. Replacement of damaged ligaments, repair of fractured bones, or

fusion of the joint, also known as arthrodesis, may be necessary to restore

function.

- Severing of the Achilles tendon is possible as a result of

blunt trauma or sharp injuries to the hind limb. If the tendon has actually

torn, surgery will be necessary to repair it. Some cases respond to

splinting or casting the leg at its full stretched length, which helps the

tendon to pull tight again as it heals.

Paw: The feline hind paw is usually made up of four digits, all

of which are weight-bearing. The first digit, the dewclaw, which corresponds

to the human thumb, sits high up on the inside surface of the hind paw and

does not bear weight. The hind dewclaws are missing at birth in cats. The

anatomy and problems associated with the hind paw are identical to the front

paw.

Problems Found in the Spine:

The feline spine is divided into five sections. First, the cervical or neck

portion consists of seven vertebrae (bones that make up the spinal column). The

first cervical bone that connects to the base of the skull is called the atlas,

and the second cervical bone is called the axis. These two bones are distinct

from all other vertebrae in their shape. These bones, along with the other

vertebrae of the spine, provide protection for the delicate spinal cord that

runs through their center, while at the same time allow for some limited

movement in the neck and back. The second section of the feline spine is called

the thoracic spine and consists of 13 vertebrae. The 13 ribs connect on either

side of the chest to these vertebrae. The third section is called the lumbar

spine and consists of seven vertebrae that correspond to the "lower back" in

people. Three fused vertebrae make up the unique section of the spine called the

sacrum found in the pelvic part of the spine in cats. The final section of the

spine is made up of a varying number of vertebrae that become smaller and

smaller as the tail tapers. These are called the coccygeal or tail portion of

the spine. Vertebrae have projections called processes that extend dorsally (up)

and laterally (sides). The processes are termed dorsal spinal processes and

lateral spinal processes. They vary in length and shape depending upon where in

the spinal column they are located. The dorsal spinal processes are the small

ridges that can be felt running the length of the back. These are very useful in

helping to count the vertebrae in the spine during examination.

Spinal column injuries can be devastating to an animal because any damage to

the delicate spinal cord running through the center of the spine can result in

permanent paralysis of portions of the body. Intervertebral disk disease, where

the cushion-like disks in between the bones of the spine become deformed, is not

commonly seen in cats. Spinal injuries and diseases are more commonly associated

with the branch of medicine entitled neurology rather than with orthopedics. The

most common type of abnormality associated with the spine in cats is probably

the kinked tail, a birth defect which is rather common among some breeds and in

some geographical areas. This defect can occur anywhere along the length of the

catís tail, but is more commonly found toward the very end. Corrective surgery

of the problem is usually not effective.

Problems Found in the Skull:

The cat skull is extremely complex. It is made up of several bone plates that

fuse together as the cat matures, as well as the two paired mandibles or

jawbones with their hinges in the back of the lower skull. The central portion

of the skull houses the brain and brainstem that are critical to the function of

the entire body. Located in front of the brain and on the sides of the face near

the nose are open compartments known as sinuses. Hollow openings at the front of

the skull house the eyes. The paired mandibles from which the lower teeth grow

are connected to each other at the very front part of the skull by a strong

ligament and are hinged at the lower back portion of the skull by a joint known

as the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The right and left maxillary bones make up

the sides of a catís nose and are connected to each other on the bottom by the

palatine bone, hard palate, or roof of the mouth. The upper teeth grow from the

lower portion of the maxillary bones as it attaches to the hard palate.

Injuries to the skull occur relatively infrequently and are usually

associated with blunt trauma, such as an automobile accident. Fractures of any

bone in the skull can occur, and depending on what organs or soft tissues are

involved, these fractures can be very serious. Head trauma with severe brain or

brainstem injury is usually fatal. Most other injuries to the mouth, nose, and

face are treatable, although permanent disfigurement can result. Because the

many different injuries that can occur to the head, each type of injury must be

managed on an individual basis and under the care of a veterinarian.

Arthritis:

Arthritis simply means inflammation of a joint. Arthritis can be broken down

into several different categories based on the type, location, and cause of

joint inflammation. Joints can be freely mobile, partially mobile, or immobile.

While inflammation can occur in any joint, the freely mobile joints and, to a

lesser extent, the partially mobile joints are those most likely to create

problems for the body when they do become inflamed.

The disk joints in between vertebrae in the spine are the most common

partially mobile joints where problems develop in the cat. Intervertebral disk

disease, where the cushion-like disks in between the bones of the spine become

deformed and cause back pain and sometimes paralysis, is not common but does

occur. Freely mobile joints include all the joints of the limbs such as the

shoulders, elbows, hips, stifles (knees), and all the joints in the paws

("knuckles"). While the specific makeup of each of these joints differs, each

contains the same basic structures.

A thin layer of cartilage overlying the bone in each joint provides for

frictionless motion. A thick, tough wall called the joint capsule attaches to

the bone on all sides and protects the delicate cartilage from damage. The joint

capsule also holds in the sticky, clear lubricating fluid that is found inside

the joint. This fluid is called synovial fluid and also helps with joint

lubrication and frictionless movement.

The three broad categories of arthritis seen in cats include degenerative

arthritis, infectious arthritis, and immune-based arthritis. Cats are fortunate

in that all three categories are relatively uncommon.

- Degenerative joint disease (DJD) is the medical term for the

degenerative type of arthritis that occurs in joints. Specific types of DJD

have already been discussed, such as hip dysplasia. The main

features of DJD are the wearing away of the cartilage and the formation of new

bone at the joint margins. Degeneration of a joint can occur as a result of a

long list of causes. Genetics, nutrition, previous injury to a joint or nearby

structures, infection, and age are some of the more common reasons for

developing this type of arthritis. DJD often gradually gets worse with time

and may become extremely severe and even crippling.

Clinical signs of this degenerative arthritis are generally limited to

signs of pain: limping, stiffness, reluctance to exercise, protectiveness and

even hissing or biting when painful areas are touched. In severe cases, the

patient may stumble or fall, slip easily on stairs or slippery surfaces, or

may become unable to walk at all if more than one limb is affected.

Because of the decrease in activity often associated with arthritis, cats

may become overweight. This creates what is known as a "vicious cycle," where

the additional weight puts extra strain on the joints, which makes the

arthritis worse. This causes the cat to exercise or move even less, leading

back to more weight gain, and so on.

Diagnosis is based upon physical examination and x-ray films. Treatment for

degenerative joint disease is complex. One approach available for some types

of arthritis is surgery. Femoral head and neck ostectomy (FHO) for hip

dysplasia is a very good example of surgical treatment for

arthritis of the hip joint. Other types of surgery may be helpful, such as

joint fusion or joint reconstruction. Decisions on whether surgery is an

option for treating joints already affected with DJD are best made with the

help of an orthopedic specialist.

Medical therapy for DJD is currently a

very complex topic. Many cats with degenerative arthritis will benefit from

medical therapy to some degree, and in many cases the improvement is dramatic.

Much of this improvement is due to general pain relief. Another benefit of

medical therapy is slowing down the progression of disease. There are two main

groups of medications that are used to treat degenerative arthritis. The first

group consists of anti-inflammatory drugs that help reduce pain and restore

function. The second group consists of nutritional supplements containing

natural hormones and other products thought to protect the joint tissues from

damage and even change and improve the makeup of the joint tissues and fluid.

Anti-inflammatory drugs have been used

over the years in the treatment of joint pain and arthritis in cats.

Anti-inflammatory drugs come in two types: steroids and non-steroids.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (known by the acronym NSAIDs) include

aspirin, flunixin meglumine, phenylbutazone, ketoprofen, and meloxicam. NSAIDs

are becoming widely recognized as an important part of the treatment of

degenerative arthritis. As cats become arthritic, the pain of movement

naturally leads to decreased exercise and activity. Weight gain then becomes a

common problem in less mobile pets. Extra weight increases stress on the

arthritic joints, leading to increased inflammation and pain. The additional

pain then causes the cat to become even less mobile, and the "vicious cycle"

mentioned previously continues. Perhaps the greatest benefit of NSAID use in

cats with arthritis is the breaking or hindering of this cycle. Use of

anti-inflammatory pain killers can keep an arthritic cat moving and

exercising, thus maintaining a healthy weight and slowing down the progression

of joint disease.

Many different types of NSAIDs have been

listed previously. This is not an indication that all are recommended or

healthy for use in cats. In fact, NSAIDs tend to have a rather narrow margin

of safety, which means that it is quite easy to create problems with them.

Cats are very sensitive to many of these drugs and they should be used with

caution and only under the direction of a veterinarian. Acetaminophen

(Tylenol), for example, can cause death in cats. NSAIDS which have been used

safely in cats include aspirin, phenylbutazone, meloxicam, flunixin, and

ketoprofen. Side effects of NSAID use include vomiting, listlessness, loose

stools, and hives.

Steroids are often used for their powerful anti-inflammatory effects in

cats, particularly because they tend to be safer than most NSAIDs. Cats are

also much less likely to experience side effects such as weight gain from

steroid use than other species.

- Infectious arthritis is the condition where an infection leads to

inflammation of a joint. There are several different types of organisms that

can infect the joints. Examples of bacterial infections, protozoal infections,

and fungal infections of joints will be discussed.

- Septic arthritis is the condition where a joint becomes

infected with bacteria, usually from a penetrating injury or bite wound.

This particular type of arthritis is discussed

below.

- Lyme Disease: Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium known as

Borrelia burgorferi and is transmitted by ticks of the Ixodes family.

Cats have a much greater resistance to Lyme disease infection than do dogs.

Rarely, lameness due to Lyme disease infection may occur in cats. Diagnosis

is generally made with serology. Treatment is effective with antibiotics,

such as amoxicillin or tetracycline. No vaccine currently exists for

prevention of Lyme disease in cats. Please see page F498 for additional

details on Lyme disease.

- Ehrlichiosis: Feline ehrlichiosis is caused by several species

of small bacteria in the rickettsial family. While the disease in uncommon,

it is seen occasionally in the western and midwestern United States. The

disease can affect all body systems, with arthritis in multiple joints being

a common clinical sign. Fever, loss of body condition, swollen lymph nodes,

pneumonia, and blood disorders may also result from feline ehrlichiosis.

Diagnosis is based on bloodwork (serology). Treatment with antibiotics is

generally very effective. Doxycycline, an antibiotic similar to

tetracycline, is the antibiotic of choice for treatment of feline

ehrlichiosis.

- Toxoplasmosis: Toxoplasmosis in cats is caused by a protozoal

parasite called Toxoplasma gondii. Generally, young or stressed cats

are the most likely to show clinical signs of disease; healthy adult cats

may become infected, but do not often show any signs of disease. Infection

occurs through ingestion of the parasite in hunted prey such as birds or

mice. A form of infective arthritis may occur along with many other clinical

signs in affected cats. Diagnosis of toxoplasmosis may be made with

bloodwork. Treatment of choice includes antibiotics (clindamycin) and

sometimes supportive care. Please see page F836 for additional details.

- Fungal arthritis: Fungal joint infections most often occur

secondary to fungal bone infections (see below under "Infections"). A

variety of fungal types may infect the joints of cats. Diagnosis is best

made with special testing of the joint fluid. A lengthy treatment with

antifungal drugs is often necessary.

- Immune-based arthritis is the third category of arthritis in

cats. The term "immune-based" indicates that these types of arthritis involve

the animalís own immune system destroying the joint tissues. Immune-based

arthritis is typically a disease of multiple joints.

- Chronic Feline Progressive Arthritis: This is a disease in cats

that is not caused by any type of infection, but may be closely associated

with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) infection. About 60% of cats with chronic

feline progressive arthritis are also infected with FeLV. The disease occurs

in 2 different and distinct forms: Rheumatoid-like progressive arthritis and

fibrous ankylosing progressive arthritis. Affected animals may have other

clinical signs such as fever, decreased appetite, and weight loss. Each form

will be discussed below.

- Rheumatoid-like progressive arthritis received its name because of

its similarity to rheumatoid arthritis in dogs and people. It occurs more

commonly in older cats and causes unstable, deformed, and painful joints.

Similar to rheumatoid arthritis, radiographs show erosion of the bones in

the affected joint where cartilage attaches. Rheumatoid factor, a

measurable substance in the bloodstream of dogs and people with rheumatoid

arthritis, is not present in cats, however.

- Fibrous ankylosing progressive arthritis occurs almost exclusively

in young male cats. Joints are swollen, painful, and stiff. New bone

growth tends to fuse joints and severely restrict their normal range of

motion (ankylosis). X-ray films show new bone extending around the joints

with loss of bone structure in general inside the joints themselves.

Diagnosis of both forms of this arthritis is based primarily on history,

physical examination, radiographs of the joint, and testing of the joint

fluid. Steroid therapy with prednisolone and other immune-suppressing drugs

such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide are the standard treatment.

Prognosis is usually guarded to poor because the disease progressively

worsens to the point of crippling lameness.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an uncommon disease in

cats that affects multiple systems in the body at one time. Disorders of the

nervous system, respiratory system, kidneys, skin, muscle tissue, blood, and

joints are commonly seen with SLE. Multiple joints typically become swollen

and painful. Affected animals may be listless, have a decreased appetite,

and may have a high temperature. If the kidneys begin to fail, an increased

thirst and need for urination may develop. Skin problems are also common.

Because SLE tends to involve so many systems, diagnosis of this disease

is challenging. Tests that may be helpful in the diagnosis of SLE include

x-ray films, joint fluid tests, and bloodwork. Testing for antibodies the

immune system creates to attack other tissues of the body, also known as "autoantibodies,"

is used in other species to diagnose SLE, but is very unreliable in cats.

Treatment is generally focused on suppressing the immune system with

steroids and other drugs. The expected outcome is not usually good and

becomes very grim if the kidneys begin to fail.

- Idiopathic polyarthritis is a "catch-all" category where all

other unknown causes of multiple joint pain and swelling are placed. Many of

the arthritis cases placed into this category appear to result from illness

elsewhere in the body or because of reactions to drugs and/or vaccines.

Infections in various places including the lungs, tonsils, urinary tract,

skin, and eyes have been linked with idiopathic polyarthritis. Disease of

the digestive tract including inflammation of the stomach, intestines, and

colon may be another cause of idiopathic polyarthritis. Some types of cancer

may also lead to inflammation of the joints. If arthritis of several joints

occurs due to any of these underlying conditions, the treatment must focus

on the specific condition. If an underlying cause can be treated and

resolved, the arthritis will usually go away. Some of these cases respond

well to treatment with steroid therapy.

Growing Bone Diseases:

Diseases of the developing bones are rare in cats. These diseases can be

present at birth or become apparent as the kittenís skeleton develops. Treatment

for these conditions is difficult and often not possible. Examples of some

unusual disorders which may be encountered in kittens include the following:

- Ectrodactyly: This condition, also known as "split-hand

deformity," results from the failure of proper growth or fusion of the bones

in the front paw, leading to a deep cleft in the paw itself.

- Osteogenesis imperfecta: This is a disorder of bone formation at

the microscopic level. It frequently results in deformed limbs, fragile bones,

and multiple fractures.

- Multiple cartilaginous exostoses (MCE): This disease causes

aggressive swelling and growth of bones near the growth plates. Some of the

swellings may become cancerous with time. This disease is listed with growing

bone deformities in general; however, it usually develops in cats after the

skeleton is already mature. There appears to be a strong correlation between

MCE in cats and infection with feline leukemia virus (FeLV). Some references

may categorize this disease with feline bone cancers.

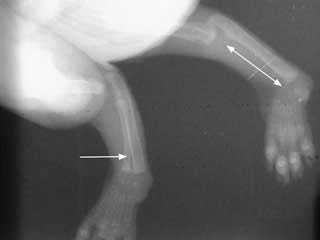

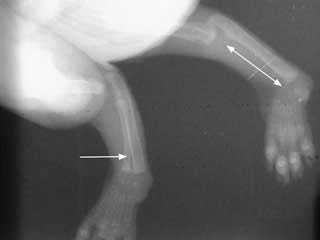

- Radial agenesis: This is a deformity in which the radius never

develops at all in the forelimb and the ulna is thicker and more curved than

normal (see figure #9).

|

|

|

| Figure 9: Radial Agenesis - The

white arrow with only one point shows the relatively normal radius on

one limb. The double headed arrow shows the place where the normal

radius should have been on the opposite limb. |

|

Neoplasia:

Neoplasia or cancer of the bones is rare in cats. The most common bone cancer

diagnosed in cats is osteosarcoma.

- Osteosarcoma is the most common bone cancer in cats and arises

from bone cells. This type of bone cancer is very aggressive in the bone

itself, but does not spread to other parts of the body as commonly as the same

type of cancer does in dogs or humans. The hind limbs are affected with

osteosarcoma about twice as often as the front limbs. The average age for cats

to develop osteosarcoma is around 10 years old; however, it has been reported

in cats ranging from 1-18 years.

The most obvious clinical signs of osteosarcoma include pain and swelling

in the affected area. When the bone cancer occurs in one of the limbs,

lameness is often very obvious early on. Depending on where the cancer occurs,

swelling of the affected area may become apparent to an owner. Another

clinical sign may occur where the cancer, after weakening the bone from which

it grows, allows the bone to break through the weakened area. This is known as

a pathologic fracture (a fracture of a bone resulting from some underlying

cause). When such a fracture occurs, sudden lameness, inability to bear

weight, pain, and swelling at the fractured area result.

Diagnosis of osteosarcoma begins with x-rays of the affected bone. Trained

professionals can come to a very high degree of suspicion for osteosarcoma

just by looking at a good quality x-ray. For a complete diagnosis to be made,

a biopsy of the cancerous tissue must be sent to a laboratory for

histopathology. A bone biopsy is a tricky procedure with the undesirable side

effect of further weakening the diseased bone. Treatment for osteosarcoma is

so aggressive and drastic, however, that an accurate diagnosis is very

important. The benefits of knowing the diagnosis outweigh the risks of

obtaining a bone biopsy in most cases. Once the diagnosis of osteosarcoma is

made, treatment should be started as soon as possible. Treatment of

osteosarcoma begins with aggressive removal of the affected bone. Amputation

of the entire affected limb is the standard approach for osteosarcoma of the

long bones of the legs. If there is no evidence of spread of the cancer to

other body systems, amputation alone without chemotherapy or other treatment

is often very effective and even considered to cure the cancer in some cases.

- Osteochondroma is a primary bone cancer that arises from

cartilage cells within the bone. A form of osteochondroma known as

osteochondromatosis can occur in which the cancerous growths may arise from

many areas of the skeleton at once. At first the bone growths are usually

benign, but with a fairly good chance of becoming malignant and spreading

cancer throughout the body. There is a possibility that osteochondromatosis is

correlated with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) infections. Diagnosis is made

with physical examination, x-rays, and biopsy/histopathology of the growths.

Treatment is difficult, especially for osteochondromatosis where the cat may

also suffer from FeLV infection.

- Fibrosarcoma is a cancer arising from connective tissue found

throughout the body, including bone tissue. It occurs only rarely in bone and

may be difficult to treat. Diagnosis is made by bone biopsy. Little is known

about how fibrosarcoma of the bone behaves in cats. Aggressive surgery is

considered the best treatment.

- Hemangiosarcoma is a cancer of blood vessel cells that has been

reported as a primary bone cancer in cats. Little is known about how it

behaves, and aggressive surgery is recommended. It has been reported to

metastasize to other sites of the body.

Secondary bone cancers: Tumors that spread from other areas of the body

to bone are called secondary bone cancers. Spreading can occur through the blood

supply to bone from distant places in the body or from tumors that grow right

next to the bone and invade it. Most commonly, secondary cancers occur in bone

from nearby tumors that invade and attack all tissues nearby. Sometimes the

source of the cancer is not known until a biopsy is obtained of the affected

bone and a veterinary specialist finds, for example, cancerous thyroid gland

cells within the bone. Treatment of spreading secondary bone cancer depends on

the nature of the cancer. Treatment of the original tumor is usually of more

importance than treatment of the secondary bone cancer. Surgery, chemotherapy,

or radiation therapy may be feasible treatment options.

Fractures:

Broken bones are the most common orthopedic problem encountered in cats.

Falls, gunshot injuries, and automobile accidents are all common causes of

broken bones in pets. This section will address the basics of dealing with

fractured bones in a practical sense for cat owners.

- Classification of fractures:

- Closed or simple fracture: This is a fracture of a bone where

the skin is not broken and no exposure to the outside environment has

occurred. The opposite is an open or compound fracture.

- Open or compound fracture: This is a fracture where exposure

with the outside environment has occurred. Examples include gunshot injuries

to bones (see figure #2) and fractures where the sharp bone

fragments have cut through the skin.

- Transverse fracture: This is a fracture where the bone is

broken into two pieces and the fracture crosses the bone in a straight,

side-to-side line.

- Oblique fracture: This is a fracture where the bone is broken

into two pieces and the fracture crosses the bone in a diagonal line.

- Spiral fracture: This is a fracture where the bone is twisted

apart.

- Comminuted fracture: This is a fracture where the bone is

broken into multiple pieces.

- Greenstick fracture: This is a fracture where the bone is

broken on one side, with the other side bent but not fractured. This type of

fracture is most commonly seen in young kittens.

- Pathologic fracture: This is a fracture due to a weakened bone

structure from any disease process (i.e. bone cancer, infection, or

osteoporosis).

- Stress fracture: This fracture results from repeated force to a

bone.

- Segmented or double fracture: This is a bone that is broken in

two or more different places.

- Managing fractured bones: The first part of treatment of a broken

bone is often done by the catís owner. Since most fractures are associated

with some kind of trauma, checking the vital functions of the injured pet

should always be done first. Alertness, breathing status, and mucous membrane

color/capillary refill time should be observed quickly and thoroughly. The

petís responsiveness and state of awareness can help assess whether the brain

and central nervous system are functioning on a basic level. Difficulty

breathing may result from internal bleeding, broken ribs, or other injuries.

Pale gum color with a slow capillary refill time occur with severe blood loss

and shock. These are potential life-threatening injuries that must take

precedence over any broken bones. Rapid transport to a veterinary hospital is

very important for trauma patients. Specific home treatment for a broken bone

can be done if there is time and if the patient is cooperative. Handling an

injured pet should always be done with cautionĖ even the most trustworthy pet

may bite or injure its owner when it is hurt. If a wound is present in

association with a broken bone, a clean bandage may be placed on the injury.

Direct pressure should be used to control any bleeding.

Once the patient is brought into the

veterinary hospital, the veterinary staff takes over, repeating the steps

listed above. Beginning with the vital signs, the patient is examined

thoroughly. Life-threatening injuries are given attention first, followed by

fractured bones. A patient must be stabilized before a broken bone is given

treatment; this stabilization process may require hours to days. A bandage is

usually placed on a fracture to help control pain and prevent further injury

until proper treatment can begin. Once the patient is stable, plans for

treating broken bones may be made.

Specific treatment for a broken bone

depends greatly upon the situation. The location and type of fracture,

availability of specialist help, nature of the patient, and cost are all

factors that influence how a broken bone will be treated. Some veterinarians

specialize in orthopedic surgery and should become involved in the more

complex bone injuries. Because these injuries usually require a great deal of

time, personnel, and training to properly treat, the cost of treating broken

bones is generally high.

There are various methods of fixing

broken bones. The broken bone must be placed into the proper position and held

there with some type of supporting device. Splints and casts are rigid

supports that encircle the broken limb and can be used for a variety of

fractures, but have limitations on how much they can do. These types of outer

support can be used with or without internal support for the broken bone,

depending upon the situation.

Other types of support for broken bones may require extensive surgery.

Metal pins inserted into the bone, wires that encircle the fracture and

tighten against the outside of the bone, and metal plates that cross a

fracture and are screwed into the bone are all common types of internal

support that are used. External skeletal fixation is another type of support

that is becoming more common in veterinary medicine. This type of support is

both internal and external because several metal pins are drilled at a right

angles to the bone with the pin sticking out of one and sometimes both sides

of the leg. These pins are then connected to each other with another metal rod

or bone cement, creating a support on the outside of the body. The type of

support used to treat any given fracture depends upon many factors and is best

left to the discretion of the veterinarian.

Infections:

Infections of bones and joints can occur in cats. Infection of bone tissue is

called "osteomyelitis" and infection of a joint is called "septic arthritis."

- Osteomyelitis is the medical term for bone infections. Bone

infections may involve bacteria, fungi, or viruses. Bacteria are responsible

for most bone infections seen in cats. Any cat may be affected, and any part

of the skeleton may become infected. Bone is typically well-protected and

resistant to infection. Open fractures, where the broken ends of the bone

penetrate the skin, are perhaps the most common way the infection reaches the

bone. Infections may also enter bone tissue following surgery, from infected

wounds near the bone, or from the blood supply. Chronic long-term bone

infections can result from open fractures and bone surgery. If a fragment of

bone dies and is left in the fracture area, new bone may form around it and

trap it inside the healed bone. The immune system cannot fight infection

inside of dead tissue since it is cut off from the bodyís blood supply. Thus

the trapped piece of dead bone provides an excellent home for bacteria and

leads to long-term infection. Diagnosis of osteomyelitis is usually made with

a good history, physical examination, and x-rays (see figure #10). Treatment

of osteomyelitis depends upon the situation. Antibiotics and surgery are the

primary means of treating bacterial bone infections. Surgery is needed in most

cases of long-term osteomyelitis to remove pieces of dead and severely scarred

tissue. Antibiotics are provided for several weeks to months.

Fungal bone infections are very uncommon in the cat, but have been

reported. Feline histoplasmosis (Histoplasma capsulatum), a deep fungal

infection, is the most common one found in the United States. Other deep

fungal infections which affect cats include Cryptococcus neoformans and

Blastomyces dermatidis.

|

|

|

| Figure 10: Osteomyelitis- The

white and black arrows point to areas of osteomyelitis surrounding the

end of this femur. There is also a pin in the femur that was used to

repair a fracture. |

|

- Septic arthritis is the term used for an infected joint. Injuries

to joints are the most common reason for infection to reach these

well-protected areas. Other sources of potential joint infections include

injections directly into a joint, surgery, and access through the blood

supply. The affected cat is usually in pain, reluctant to bear weight, and may

have a fever. The joint may be hot and swollen. Diagnosis of a septic joint is

achieved by history, physical examination, x-rays, and by testing a sample of

the joint fluid. The joint fluid analysis is the most helpful of the tests in

showing the actual infection. Culture and sensitivity (see page

D135) may be

performed on the fluid, often providing very helpful information for

treatment. Septic arthritis is a difficult problem to treat. There is usually

extensive and permanent damage done to the delicate tissues of the joint,

which results in permanent pain and arthritis even after the infection is

gone. Surgery to relieve swelling and pressure, flushing the joint with

sterilized fluid, and removing any clumps of infected material is usually the

best approach. Sometimes, the joint must be left open and carefully bandaged

to allow it to drain. Administration of antibiotics for at least 4 weeks is

very important regardless of the surgical approach. The outcome is very

questionable, and permanent damage resulting in arthritis of the joint is not

uncommon.

Summary: Orthopedic problems are a common occurrence in veterinary

medicine. The key to successfully treating these problems is early detection and

proper treatment. The petís owner plays an essential part in identifying

problems early and then seeking the proper medical attention. In general, if

lameness in a pet lasts longer than 24 hours, the lameness is getting worse, or

there is an obvious injury, veterinary advice should be sought.