BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just like it!

View some of the 10+ Video clips found in the Equine Manual

foot | pastern and fetlock | canon bone regions | knee and upper front limb | hock | stifle and upper hind limb | neck region | different joints and locations | nutrition and supplements

Introduction:

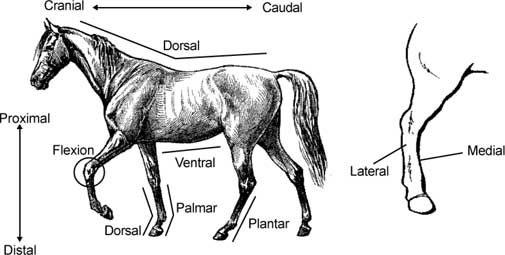

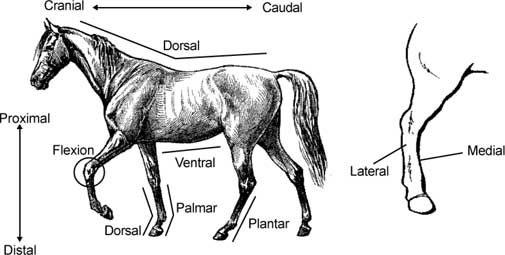

Today’s horse is a highly trained athlete that is often pushed to the very limits. Because of this, tendon, bone, hoof, and joint problems are some of the most common injuries many horse owners encounter. One of the keys to identifying and then treating these problems is understanding the terms and anatomical structures that may be involved. Another key is understanding the function of certain tendons, ligaments, and bones. To help understand these structures and their function, the pictures and captions on pages A28, A30, and A35 are essential. The following diagrams and definitions are also of benefit.

Terms:

Diagnosing a Problem:

Many times it is obvious that an injury has occurred. Other times the injury may be old, or the horse may not be showing significant signs of lameness. The suggestions, pictures, and information found on pages B885 and E460 can help a horse owner identify a lameness problem. The following information will identify the specific tendon, ligament, joint, bone, and foot problems that are common in horses. For the most part, the information will be broken down into sections based on anatomical location of where the problem is occurring. For example, all problems associated with fetlock will be discussed together in alphabetical order. A general category is found towards the end that contains problems that can be found in many different joints or locations. Details on the cause, clinical signs, diagnosis, and treatment of each problem will be included as needed. A brief discussion on the role of nutrition and supplements in bone and joint problems is also found at the end of the discussion.Note: The following reference has been used extensively to generate much of the information contained in this discussion: Ted S. Stashak, DVM, MS. Adams’ Lameness in Horses. Lea and Febiger, 1987.

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just like it!

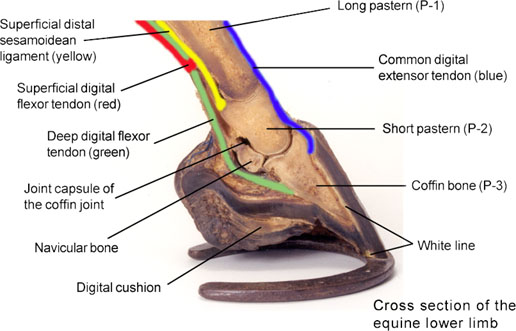

Figure 1

|

|

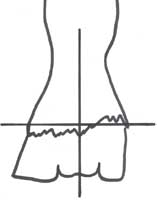

Treatment: The key to treating this problem is to bring the foot back

into balance by trimming the long heel. Some cases may resolve by simply

trimming and then letting the horse go bare foot. In other cases, the long heel

should be trimmed and a full bar shoe should be used to distribute the horse’s

weight evenly around the foot. With successive trimming and shoeing, the foot

can eventually come back into balance with both heels evenly on the ground

surface. In very severe cases, a normal return to function may not be

achieved.

Causative Agent: Sidebone is caused by concussion forces being placed

on the collateral cartilages. The collateral cartilages are found on either side

of the coffin bone of the foot and extend up past the coronary band. With

continued traumatic forces, the collateral cartilages begin to turn to bone (or

ossify). Sidebone is usually found in the front feet of horses that have

conformation problems. Animals that are base-narrow or base-wide have the

tendency to develop this problem.

Clinical Signs: Pain and heat are often noted over the collateral

cartilages during the active stages of the disease. The cartilages that are

involved will often be harder than normal and painful to the touch. These horses

may or may not be lame.

Diagnosis: It is often easy to falsely conclude that sidebone is the

cause for a horse’s lameness. Sidebone should not be diagnosed as the cause of

lameness unless there is heat and pain associated with the collateral

cartilages. Radiographs showing the cartilage turning into bone can be used to

identify this problem. This finding alone, however, is not sufficient to

diagnose sidebone without the associated signs of heat and pain.

Treatment: Some farriers recommend that the hoof wall over the

sidebone areas be thinned or grooved. These processes allow the foot to expand

and be more flexible. If fractures of the sidebone occur, they need to be

surgically removed. If pain and heat are still present, treating with

phenylbutazone can help. All cases should be rested until the inflammation has

subsided. In general, many cases are not lame and do not require treatment

unless there is active pain and heat.

Causative Agent: Thrush is caused by an infection of anaerobic bacteria and

potentially other organisms in the frog and sulcus (commissure). These organisms

infect horses that are kept

in moist, dirty environments, where the foot is continually dirty and wet. Feet

that are improperly shod or are improperly trimmed are also at risk of being

infected.

Clinical Signs: In most cases the commissures of the foot are full of a

dark, foul smelling discharge. The commissures are often deeper than normal, and

the frog can be loosened from the underlying tissues. In severe cases the

organisms can be infecting the sensitive structures of the foot causing lameness

and infections going up the limb.

Treatment: The treatment for thrush involves keeping the foot clean, dry,

and properly shod. After the foot is completely cleaned with a hoof pick and

knife, topical medications such as povidone-iodine (Betadine), chlorhexidine, or

Kopertox should be applied on a daily basis until the infection is cleared.

Causative Agent: Cracks can start from the bottom or the top of the hoof

wall and extend variable distances. The cracks that start at the coronary band

are usually caused by some type of trauma or injury to the coronary band. The

cracks that start at the bottom of the foot are most often caused by letting the

foot go too long without trimming. Excessive drying of the foot can also make it

more susceptible to cracking.

Clinical Signs: Depending on the severity of the cracks, some horses may

be lame. Some cracks may become infected and discharge blood or pus.

Treatment: The treatment for each crack will depend on its location,

depth, and how far up or down the hoof wall it extends. Any cracks with signs of

infection, should be treated with povidone-iodine (Betadine) and bandaged until

the infection is cleared. Current treatments for many cracks involves the use of

synthetic epoxy and hoof repair materials. Before these materials are placed in

the crack, the crack should be thoroughly cleaned and possibly burred out to

enlarge the area for the glue or plastic to adhere. Some horses should be shod

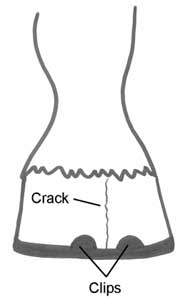

with toe clips placed on either side of the crack to prevent it from expanding (see figure

2).

Figure 2

|

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just like it!

Problems in the Pastern and Fetlock

| Figure 3: Mild windpuffs |

|

Treatment: In many cases, resting the horse will help alleviate the

problem. In younger horses, the problem will often leave as the horse grows.

Pressure wraps and topical DMSO can be used if the problems persist.

Thorough-pin is the common term for tenosynovitis in the tarsal sheath that

surrounds the deep digital flexor tendon in the hind limb. This condition can be

identified by noting swelling of the tendon sheath above the fetlock on the back

of the hind limb. Thorough-pin is a mild form of tenosynovitis and should be

treated like a horse with windpuffs. Like windpuffs, the swelling in

thorough-pin is not hot, and the horse should not be painful or lame. Often the

cause of thorough-pin is not known.

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just like it!

Problems in the Cannon Bone Regions (Metacarpus, Metatarsus, and Splint Bones)

| Figure 4: Splint |

|

Diagnosis: Many cases can be identified by the clinical signs (location,

swelling, heat, and pain). If a fracture of the splint is involved, the swelling

and pain may be more extensive and severe. In some cases radiographs will need

to be taken to determine if a joint or the cannon bone is involved. If

interfering is suspected, place white chalk on the inside hoof of the opposite

limb. Work the horse and watch for evidence of chalk on the splint area.

Treatment: The treatment will vary depending on the cause; therefore, it

is important to determine the exact cause of the splints. For interfering

problems, using good splint boots will help resolve the problem. The idea behind

splint boots is to prevent the opposite limb from contacting the shin (cannon)

area. These boots contain some type of thickened material for protection. The

key to placing the boots is not necessarily how tight they are, but that they are placed properly to protect the shin

(cannon) bone areas. The horse should also be evaluated (by owner and farrier)

for any trimming or shoeing reasons for the horse to interfere. Most

conformation problems are difficult to correct. If nutrition in a young horse

might be the problem, use the information on page A575 to calculate what is

being fed. If the ration seems too hot, take measures to decrease the amount of

energy (TDN) being fed.

Anti-inflammatory agents (bute,

topical DMSO) and cold water soaks are essential for splints that are painful, tender, and

swollen. Cold water/ice can be applied

20 minutes twice a day for 5-7 days. After the soaks, pressure wrapping the

involved areas can also help. Rest is also essential until the inflammation has

gone down (30-45 days). If the splints are more chronic (have been going on for

some time), the above may not be useful. In these cases the extra bone may have

to be removed by surgery. In general, if the initial inflammation is reduced

early on, the outcome is usually favorable. It is also essential to remove the

cause (nutrition problems, interfering, etc.). Most splints resolve with time

and proper treatment.

Introduction and Causative Agent: All of these terms are used

to describe injury to the cannon bone that takes place when severe compression

forces are placed on the limb during impact. When bone remodeling cannot keep

up with the repeated stresses, defects in the bone occur. These injuries most

often occur in young animals (2-3 years of age) that are under extensive

training programs.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: In the acute, mild form of the disease,

the horse may be in pain when pressure is placed on the involved area of the

cannon bone. The horse is usually only sightly lame and the condition may even

go unnoticed. If the problem progresses, swelling may be felt on the

front/middle (dorsomedial) surface of the cannon bone. The pain is usually more

severe at this stage. In the early part of this problem, radiographs are often

normal. As the problem progresses, radiographs may show a subperiosteal callus

forming in the injured areas of the cannon bone. These calluses are the way the

bone tries to heal itself by laying down extra bone for added strength.

Occasionally, fractures are observed on a radiograph.

Treatment: For the more mild cases, rest and daily hand walking are

recommended. This should be continued until the cannon bone is no longer painful

to pressure. After this, the horse can be placed on a controlled exercise

program. The length and duration of the controlled exercise program is

determined by how well the cannon remains unpainful. Anti-inflammatory agents

are also of benefit. For the more severe cases, the extent of rest may go as

long as one year. There are some surgical procedures for those cases that do not

respond to rest and anti-inflammatory agents.

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just like it!

Problems in the Knee (Carpus) and Upper Front Limb:

Problems in the Hock (Tarsus):

Clinical Signs: The excess joint fluid causes soft, fluid filled bulges to appear on the inside and outside areas of the hock (see figure 5). Like windpuffs, these swellings are not hot, and the horse should not be in pain or lame unless the bog spavin is due to an injury or OCD lesion. As pressure is placed on one of the swellings, the fluid will be pushed to other swellings and make them larger.

| Figure 5: Bog spavin |

|

Diagnosis: It is important to determine the exact cause for the joint

swelling (OCD, trauma, nutrition, etc.). To do this a radiograph is a must.

Clinical Signs/Diagnosis: These horses

often have a history of being moderately lame after exercise, but improve with

rest. These horses are positive to the spavin or hock flexion test. To perform a

spavin test, the limb should be held in this position, with the cannon bone

parallel to the ground, for 1-2 minutes (see

figure 6). Once the limb is released, watch the horse for signs of lameness as

it is trotted away. Because of the inflammation to the periosteum (periostitis),

extra bone is formed over the front and inside areas of the hock joint. As a

result, a firm, boney bump can often be detected on the inside (medial) portion

of the lower hock (see figure 7). Radiographs are very important in diagnosing

this disease. Multiple views of both hocks are often necessary to help identify

the problem.

Video clip of a spavin test being performed. If the video

does not play, you must install an MPEG video

Treatment: In many cases of bone spavin, treatment efforts are not very

effective. Many horses remain lame and never return to full function. There are

various surgical techniques that can be used to help treat bone spavin. The most

common is a procedure called a cunean tenectomy. This procedure removes the

portion of the cunean tendon where it moves over this region of the hock.

Corrective shoeing can also help many of these horses. The intent of the

corrective shoeing should be to cause the foot to break-over quicker. This can

be accomplished by using a rocker or rolled toed shoe.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Signs of heat, swelling, pain, and lameness

are common early on in the condition. As things progress, scar tissue and an

obvious bump may be noticed (see figure 8). Radiographs can help determine the

cause and extent of a suspected case of curb.

Treatment: In many cases, resting the horse will help alleviate the

problem. Rest should be accompanied by ice packs, anti-inflammatory agents, and

corticosteroid injections under the skin in the area of the lesion. In cases

that have been going on for sometime, successful treatment may not be

achieved.

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just

like it! Problems in the Stifle and Upper Hind Limb

Treatment: In many cases, resting the horse will help alleviate the

problem. In younger horses, the problem will often leave as the horse grows. If

the problem is due to OCD, surgical treatment of the lesion is necessary. When

nutritional deficiencies are the cause, supplementation is required. If the

problem is severe or the horse is lame and painful, injections of

corticosteroids and other products may be given in the joint. Some of the

anti-inflammatory and glycosaminoglycan products may also be of benefit. Because

no treatment seems to be 100% effective, bog spavin is sometimes a difficult

problem to completely cure. This is particularly true if the problem is caused

by a conformation defect or trauma.

Introduction and Causative Agents: Bone spavin is found most often in

horses that are ridden at high speeds, where they are used for jumping, reining,

roping, and cutting. Damage and inflammation occurs in the lower bones and

joints of the hock when compression and rotation stresses are placed on the hock

during these exercises. Like bog spavin, these injuries are often the result of

poor conformation (straight, cow, or sickle hocked). Some studies show that

nutritional imbalances and deficiencies may also play a role in this disease.

Figure 6: Spavin test

player on your computer (e.g. Windows Media Player).

Click here to

download Windows Media Player.

Or

Install Internet Explorer from our CD Manual.

Figure 7: Bone spavin

Introduction and Causative Agents: Curb is a condition where the back

(plantar) aspect of the fibular tarsal bone is enlarged. This results from an

enlargement of the plantar ligament due to inflammation and thickening. In some

cases periostitis is involved and there is an extra layer of bone in that

region. The plantar ligament is located in the area just below the point of the

hock. Inflammation of the plantar ligament is often the result of poor

conformation (straight, cow, or sickle hocked) or when the horse injures itself

in the hock region by kicking against trailers or walls.

Figure 8: Curb

Introduction: The patella is the horse’s knee cap. It can be

fractured, luxated, or become fixated or "stuck."

Causative Agents: Luxations and fractures are due to trauma caused by

kicks and collisions. Luxations can also be due to congenital abnormalities. The

upward fixation of the patella is caused by genetic traits where the horse has a

"straight hind limb" conformation. Poor muscling and muscle tone can

also be part of the problem. In this situation, the patella becomes fixed or

catches on a ridge (medial trochlear ridge) of the femur. This prevents the limb

from flexing.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: When luxations and fractures are the

problem, the stifle will be swollen and painful. The horse may show varying

degrees of lameness. Radiographs are also helpful in diagnosing these problems.

If the horse has a problem with upward fixation of the patella, the limb may

actually be "locked" in a flexed position where the stifle and hock

cannot flex. If the horse is only "catching" the patella on the ridge,

the horse will have a jerky gait when turned in a circle or walked up or down a

hill.

Treatment: For luxations and fractures, surgical procedures can be

used to help treat the problem. For minor fractures, stall rest and splints may

be all that is needed. Treatment for a fixed patella depends on how severe it is

and if the patella is "locked" or just "catches." For

immediate treatment of a locked patella, the limb can be pulled forward, while

pressure is placed on the patella to force it down and medially. The horse can

also be backed down a hill, while the same pressure is placed on the patella to

force it down and medially. Some recommend startling the horse, causing the

patella to release. This should be done with caution because of the potential

for additional injury. In the more severe cases, surgery can be performed to cut

the medial patellar ligament. This allows the patella to release and prevents

any additional locking of the patella on the medial trochlear ridge of the

femur. Once the surgery is performed, the horse should not be used for at least

6 weeks.

Prognosis: For luxations, the prognosis is guarded to poor. For fractures

of the patella, the prognosis can be favorable if proper and thorough treatment

is implemented. The prognosis for upward fixation of the patella is good as long

as the joint has not suffered any permanent damage.

The following video clip shows a pony with a fixated

patella in the left hind limb. The patella remains fixated throughout

the entire video.

|

If the video

does not play, you must install an MPEG video |

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just

like it! Problems in the Neck Region

Introduction: Fractures of the tibia, femur, and pelvis will be

discussed below. In general, fractures that occur in foals have a greater

chance of being treatable. Direct injury or trauma to the area is usually the

cause of these fractures. This injury can come from a kick, severe compression

forces, or accident (collision). The resulting injury can be anything from a

fissure fracture to a comminuted (multiple pieces) fracture.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: Non-weight bearing lameness is often

noted with these fractures. In most cases, swelling, pain, and crepitus

("grinding") can be found when the area is handled and manipulated.

Diagnosing these injuries is not usually difficult and radiographs are the best

way to determine the extent and type of fracture.

Treatment and Prognosis: In general, most significant fractures in the

tibia or femur of an adult horse are difficult to treat. Many of these horses

should be euthanized. This statement is also true for many fractures of the

femur in a foal. On the other hand, some minor fractures of the tibia can be

treated with only strict stall rest. The more complicated fractures of the tibia

and femur in a foal can sometimes be treated with surgery and/or cast

application. During the surgery, plates, screws, and pins may be used to hold

the fracture in place. There is no surgical treatment for fractures of the

pelvis. A fractured pelvis may be treated with strict stall rest for as long one

year. Slings may also be used for the first 6-8 weeks. Because there is such

variability in the types and treatments of these fractures, a veterinarian must

be involved in each individual case.

Again, no matter what type of fracture has

occurred, attention should be given to the opposite limb. In many cases, the

opposite limb will be forced to bear most of the weight. This can result in

laminitis and other problems.

Some foals with these types of fractures

do fairly well after successful treatment. If the horse is a yearling or adult,

the fracture has broken the skin, or the fracture is comminuted, the prognosis

is poor.

Introduction: The term "wobblers" is often used to describe

any condition of the horse where weakness and coordination problems are

involved. This condition can be caused by deformed vertebrae in the neck

(cervical vertebral malformations), equine protozoal myeloencephalitis

(EPM),

equine herpes, equine infectious anemia, trauma, and others. This discussion

will describe wobbler syndrome caused by deformed vertebrae in the neck. The

other conditions have been discussed elsewhere in this manual.

Causative Agent: Wobbler syndrome is caused by a defect in the

vertebrae of the neck that compresses the spinal cord. The deformed vertebrae

can compress the spinal cord all the time or only when the neck is flexed.

Studies indicate that this condition has some genetic and nutritional influences

that cause the vertebrae to not form properly. Horses that are fed high energy

diets, grow rapidly, and are large at a young age are more at risk.

Clinical Signs: Ataxia (balance problems), gait abnormalities, and

weakness are some of the common signs. Many horses are in pain and reluctant to

move their necks. Some horses recover and remain fairly normal, while others

digress to an unmanageable state.

Diagnosis: A physical exam will help to identify the possible location of

the problem. Radiographs are essential to determine exactly where the problems

are located and the severity of the deformities. These examinations may also

reveal degenerative joint disease (DJD) and osteochondritis dissecans (OCD)

lesions.

Treatment and Prognosis: Some mild cases may respond to anti-inflammatory

agents (steroids, bute) that help to reduce the inflammation in the spinal cord

and surrounding areas. This type of treatment only produces temporary

improvement, with the horse continuing to have problems. In most cases the

surgical treatment is a must. The surgical procedures that are commonly used are

designed to provide increased stability to the neck vertebrae. Most surgical

cases can return to breeding and a few horses may return to normal or near

normal function. Horses that show few clinical signs prior to surgery, have a

better chance of gaining a favorable recovery.

Problems Found in Many Different Joints and Locations

When abnormal amounts of

weight and pressure are placed on a growth plate or area of endochondral

ossification, the growth is stunted. For example, one way to cause a carpus

valgus deformity in a foal is to have an injury or poor conformation that causes

abnormal weight to be placed on the outside regions (lateral aspect) of the bone

(radius) above the knee (carpus) in the front limb. In this case, the outside

portion of the growth plate will NOT grow properly, while the inside (medial

aspect) will continue to grow. This causes the bone (radius) to cup or dish,

forcing the knees together. Nutritional imbalances, injury, and improper weight

bearing can also cause the growth plate to become inflamed (physitis) or even

close prematurely. This can result in abnormal growth and angular limb

deformities.

Clinical Signs: In severe cases, it is obvious that there is a problem

just by looking at the limbs. The horse may be lame and have swollen and painful

joints or growth plates.

Diagnosis: Radiographs are essential in identifying the location and

severity of the problem. A complete history should be taken and include the

following questions: Was the foal born this way? What is the diet? Was the mare

overweight during the pregnancy? Have there been any injuries to the limbs or

limb? A diagnosis can be reached based on the history, physical exam, and

radiographs.

Treatment: Treatment in all cases varies according to the cause of the

deformity. In general, there are three common avenues of treatment:

In general, if the problem is corrected early, most young foals have a

successful outcome.

Introduction: Flexural limb deformities are situations where the

various joints of the body are held in some degree of flexion. This is most

often the result of a contracted tendon. These problems are identified as

congenital (present at birth) or acquired (occurring after birth).

Causative Agents: Congenital deformities are most often caused

by malposition during the pregnancy, the mare ingesting toxic substances, and/or

inherited genetic defects. Acquired defects are often the result of pain

(epiphysitis, osteochondrosis, injury), genetics, nutritional imbalances

(excessive energy intake), and rapid growth. A combination of two or more of

these problems may also be the cause in some cases.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis: In many cases more than one limb is

involved. Most of the time the knee (carpus) or fetlock is involved, and these

joints are often "popped" forward. The joint is held in this flexed

position, and may or may not be forced to a normal position with pressure. The

acquired cases will often result in a "club foot," where the horse

bears its weight on the toe.

Treatment for Congenital Deformities: Some horses will correct the

problem on their own with little or no human intervention. More complicated

cases can be helped/treated in one of three ways:

| Figure 9: Carpal hygroma |

|

Clinical Signs: Some pain, heat, and swelling are the most common signs.

If the injury is significant, the swelling can be quite large and there can be

some soft tissue thickening.

Treatment: In most cases, the bursitis can be treated with ice packs,

anti-inflammatory agents, and rest. It is also important to prevent additional

injury to the bursa (remove the shoe on that foot, etc.). For more severe cases,

injections into the problem area and surgery may be required.

Introduction: "Epiphysitis" is a problem that is commonly

found in young, growing animals (ages 4-8 months) and young horses beginning

training. The term "Epiphysitis" is somewhat misleading because the

problem actually involves the growth plate and not the end (epiphysis) of a long

bone.

Causative Agents: Fast growing, young animals that are fed high grain

rations seem to have the most problems. Genetics may also play a role in the

fact that faster growing foals experience epiphysitis. Abnormal weight bearing

and trauma/injury to the growth plate are sometimes associated with this

disease. Studies indicate that a combination of these influences is often the

cause. With the above being the known causes for epiphysitis, how they actually

cause the disease is less understood.

Clinical Signs: The most obvious sign is a "flaring" or

enlargement of the ends of the long bones. This commonly is seen above the knees

on the end of the radius. As the problem progresses, the end of the bone begins

to take on a "hour glass" shape. Depending on the severity of the

disease, the horse may or may not be lame. The horse may act painful when the

involved area is palpated or handled.

Diagnosis: Physical exam and radiographic images are often sufficient

to diagnose this problem.

Treatment and Prevention: The most important step in treating and

preventing this disease is to evaluate and adjust the horse’s ration. Any

nutritional imbalances should be corrected. Use the information found on page

A575 and the details contained below on nutrition to help calculate a proper

diet. Mineral analysis may need to be performed to determine any deficiencies or

excesses of the trace minerals. If the horse is over weight, restrict the amount

of energy being fed. Some horses may recover with rest and the proper use of

anti-inflammatory agents (bute). If anti-inflammatory agents are used, the foal will use the limb

more as the pain and inflammation is reduced.

This potentially can result in additional injury and epiphysitis. If radiographs show that

there are other problems (OCD lesions, angular limb deformities), these will

need to be corrected to help alleviate the epiphysitis. Many horses seem to

recover with time and rest; however, they never return to full performance

ability.

Introduction and Causative Agents: A luxation is a dislocation of a

joint and can occur in the fetlock, knee (carpus), shoulder, hock (tarsus),

stifle, and hip. These injuries most often occur when the limb is forced in an

abnormal direction. This can happen when the horse steps in a hole, falls,

slips, jumps, or twists the limb while in a flexed or extended position.

Clinical Signs: The limb that is involved often has a angular

deformity, where the portion of the limb distal to luxated joint is deviated

outward or inward. The joint itself maybe swollen, painful, and unstable. There

will also be varying degrees of lameness.

Diagnosis: Diagnosing the location of these injuries is not usually

difficult. Radiographs are the best way to confirm a diagnosis and determine if

any fractures are involved.

Treatment: Treatment for most luxations requires that the horse be

anesthetized and the dislocation be reduced or put back into place. This should

take place as soon as possible after the injury. Depending on the location of

the luxation, casts may also be applied. Any chip or other type of fracture

should be treated appropriately.

Prognosis: Many of the minor luxations where no fractures are involved

will often have a good recovery and return to performance. Luxations of the hip

joint, however, may never return to normal even after the head of the femur is

put back into place. If fractures, infection, or degenerative joint disease (DJD)

occur, the prognosis is poor.

Introduction: Osteochondrosis is a defect in the normal development of

cartilage. This defect occurs sometime in the process of endochondral

ossification. Endochondral ossification is where cartilage (in the epiphysis or

ends of the long bones) actually ossifies to form bone. If endochondral

ossification does not progress normally, defects called osteochondritis

dissecans (OCD) or subchondral bone cysts can result. OCD lesions are places

where fragments or flaps of cartilage associated with the joint are separated

from the rest of the cartilage. Bone cysts are areas in the end of the bone

where endochondral ossification does not progress normally. This leaves small

areas of cartilage deep within the end of the bone. These areas necrose or die

and leave a defect in the end of the bone.

Causative Agents: The following are thought to cause these defects in

a growing animal:

Causative Agents and Clinical Signs: In most cases, these problems are

caused by severe straining and over-stretching of the tendon or ligament. This

can occur when excessive loads are placed on the limbs due to sudden turns,

jumping, stopping, or slipping. Things such as improper shoeing, poor

conformation, and traumatic injuries can also cause a problem to develop. When

injury occurs to the tendon, the tendon fibers can be damaged and the blood

supply can be compromised. Severe injury can result in complete rupture of the

tendon.

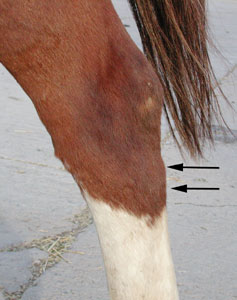

Clinical Signs: After the initial injury, the involved area is swollen,

painful, and hot to the touch. The horse is often lame and very painful when the

limb is flexed. These injuries can occur in the flexor tendons located behind

the cannon bone ("bowed tendon") in the area just below the knee or hock and

above the fetlock (see figure 10). In some cases it is an injury to the anular

ligament that causes the problem. The anular ligament wraps itself around the

fetlock area (kind of like shrink wrap) and helps to keep all the tendons and

joint structures encapsulated. If the anular ligament becomes inflamed, it may

begin to scar and shrink. The superficial flexor tendon runs just beneath this

anular ligament. If the anular ligament scars and constricts, the flexor tendon

is "pinched." This can be the cause of the swelling above a fetlock

joint. If these problems continue for prolonged periods of time, the tendon can

begin to scar and adhere to surrounding tissues. This will cause a loss of

function and flexibility of the tendon/ligament. In some cases the navicular and

sesamoid bones may be involved. If the sesamoids are inflamed, it is called

sesamoiditis.

| Figure 10: Bowed tendon |

|

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just

like it! Nutrition and Supplements: Proper nutrition plays an essential role in the development of healthy bones,

muscles, and related structures. Consuming rations that contain imbalances in

protein, minerals, and vitamins can cause abnormal bone development. Too much

feed intake can be as detrimental as too little feed intake. Because most of the

nutrition related problems occur in foals, attention should be given to the

ration being fed to a pregnant/lactating mare. In general, if the mare does not

consume sufficient amounts of a properly balanced diet, overall milk production

will be low, and the milk will lack the essential vitamins and minerals

(calcium, phosphorus, vitamin A, copper) necessary for a healthy foal. If the

mare consumes too much high quality feed, she will be overweight and still not

produce sufficient quantities of milk for the foal because of excess fat

deposits in the mammary gland. An overweight mare will also not breed back as

well. Pregnant mares and ones that are lactating should be feed a diet that is at

least 12-14% protein on a dry matter basis. Their milk should contain 80-120

mg/dl of calcium and 45-90 mg/dl of phosphorus. They should be fed a balanced

ration that contains vitamin A, copper, zinc, and possibly manganese. Because

the mare’s ability to produce sufficient quantities of milk declines with

time, it is important to begin creep feeding foals at a young age (3-4 weeks).

Remember, however, that feeding foals excess protein (greater than 2% of the

foals requirement), zinc, selenium, and iodized salt, can result in bone, hoof,

and hair problems. Additional information on creep feeding and nutrition can be

found on pages A249 and A575. In many cases, the use of dietary supplements is not necessary and can even

be detrimental to the horse. This statement is true only if the horse has access

to sufficient amounts of a balanced diet. Supplements should be used when a

deficiency in the diet is present, a specific joint disease is diagnosed, or

when the horse has the potential to develop a joint, muscle, or tendon problem. To fully understand the common supplements that are used to maintain healthy

joints, it is important to know something about what makes a healthy joint. Many

of the joints in the body (knee, hock, fetlock, etc.) contain cartilage and

synovial or joint fluid. These joints are surrounded by a synovial membrane and joint

capsule. Healthy cartilage and synovial fluid are essential in order to provide

a low friction, smooth surface for the bones of the joint to move against and

impact with. Realize that stresses placed on the joint during training and

competition cause wear and tear to the joint cartilage and inflammation. If

damage is severe or the inflammation continues for extended periods of time, the

cartilage and joint can be permanently injured. Articular cartilage has the ability to replenish itself when mild damage

occurs. It does this by producing collagen and proteoglycans. Collagen is a

protein that provides the strength of cartilage, while proteoglycans (made of

glycosaminoglycans) provide resistance to compressive forces. Most of the joint

supplements contain raw materials or nutrients that are required to allow the

cartilage to replenish itself and ingredients that help reduce inflammation in

the joint. Glucosamine HCI, chondroitin sulfate, and methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

are some of these ingredients. Glucosamine is required for the production of

glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans. It also helps reduce

inflammation. Chondroitin sulfate is one of the major glycosaminoglycans found

in cartilage and also helps to reduce inflammation. Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

acts as an anti-inflammatory and general pain reliever. The following list identifies some common joint/muscle/tendon supplements

that can be useful in many horses: The following are products that can be injected or given orally to help

relieve joint inflammation and pain: Summary: In conclusion, joint, bone, tendon, and ligament injuries can

often be challenging problems to diagnose and resolve. If a problem does not

improve with routine treatments, be sure to involve a local veterinarian.

BUY THIS MANUAL NOW and have access to this article and 100's of others just

like it!

View More of the 10+

Video clips found in the Equine

Manual

Diagnosis: Many cases are identified based on physical exam and

clinical signs. The severity of the problem can often be determined through the

use of ultrasound and radiography.

Treatment: The key to healing acute tendon/ligament problems is to reduce

the inflammation and keep any additional trauma and swelling from occurring.

Treatments to reduce the inflammation include cold water soaks or ice packs for

20 minutes twice a day for the first 2-3 days and anti-inflammatory agents (bute).

Topical DMSO can also be beneficial in reducing the swelling. Pressure wraps and

even casting can be used in more severe cases to prevent additional stretching

and injury to any of the tendons and ligaments. To prevent additional injury,

strict stall rest (for the first two weeks), followed by mild manipulations of

the injured area, should be used. To help build the tendon, regularly pick up the

foot/leg and move it gently through a series of flexing motions.

Excessive flexion, particularly where the horse shows pain, will cause continued

damage and should be avoided.

After the rest and mild manipulations, carefully choose what activities the

horse is asked to perform. These should be low impact and preferably without a

rider. Some minor tendon stretching will occur with normal use. After

these occasions, reduce the chance for inflammation and swelling by using cold

water soaks and anti-inflammatory agents as needed. If continued irritation

occurs, scaring and permanent injury will result.

For the more chronic tendon/ligament injuries, where scarring and boney damage

may be involved, surgical intervention is often required. There are many

different procedures that can be used. An equine surgeon will need to evaluate

each situation before a recommendation can be given. The usual treatment for

bowed tendons caused by anular ligament problems is a surgical procedure where

the anular ligament is cut. This allows the flexor tendons to move more freely.